Cartoonist George Booth: A Real New Yorker

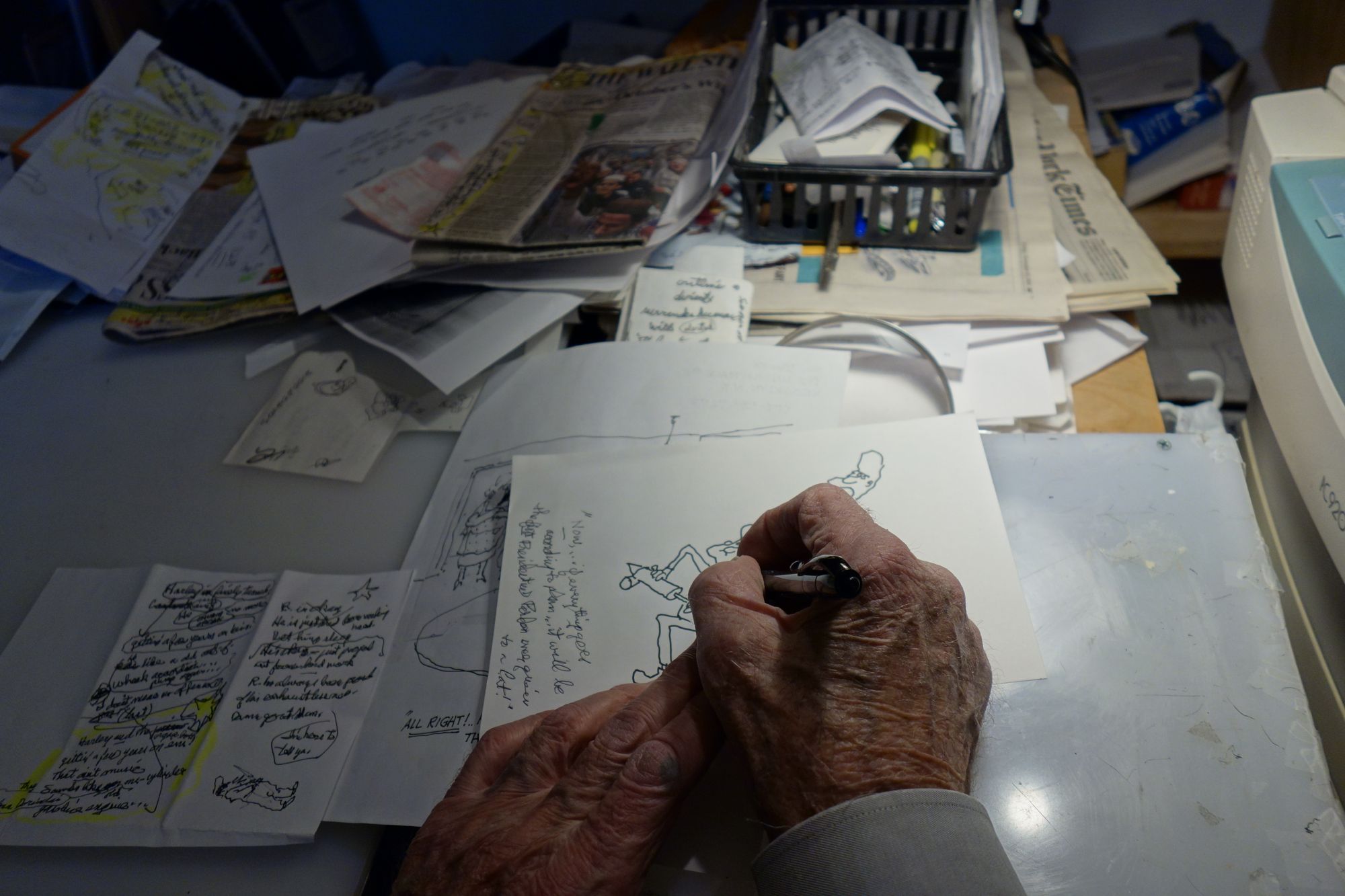

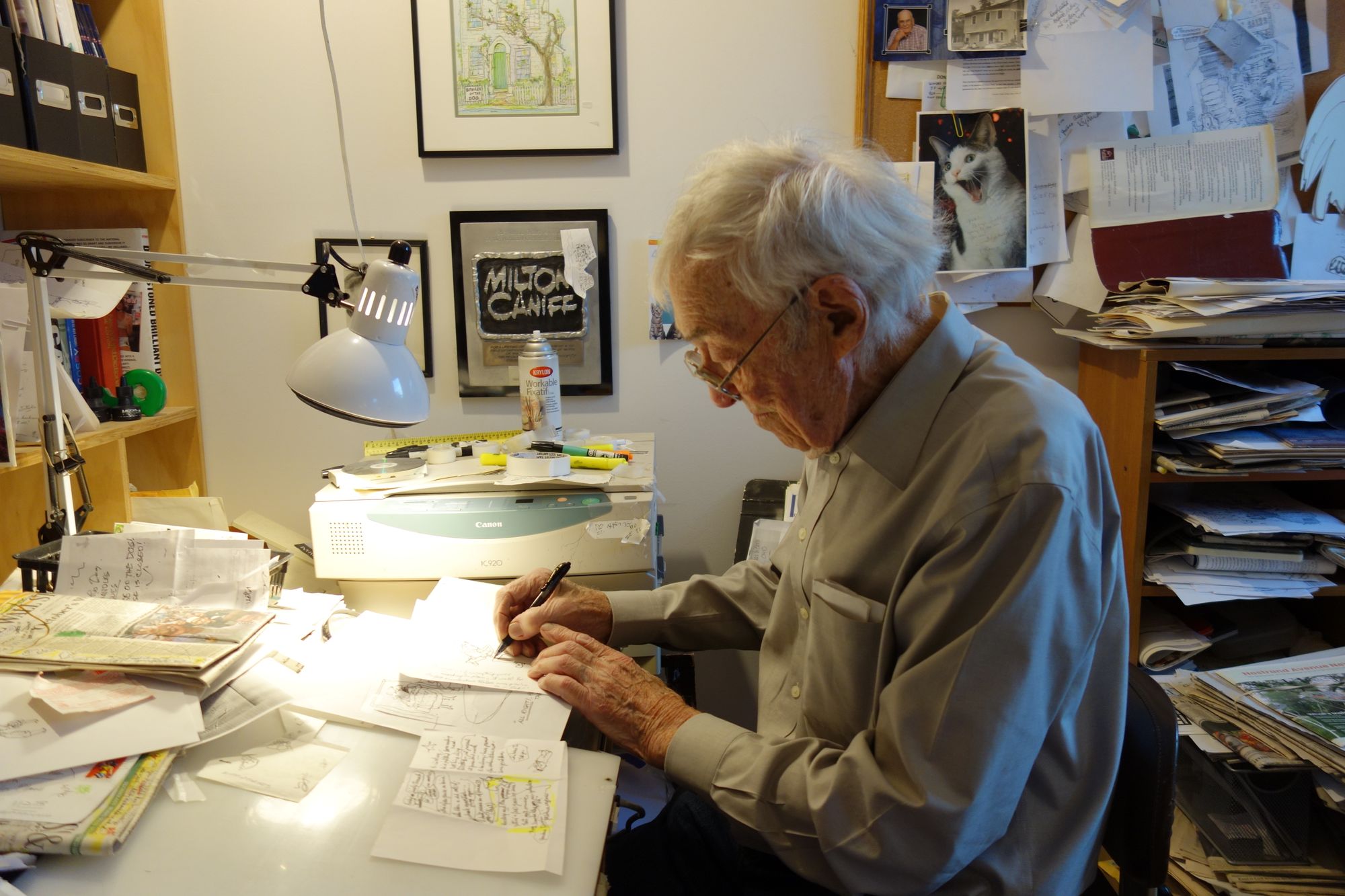

CROWN HEIGHTS — Martinsville, Missouri is a long way from Crown Heights, but that’s where cartoonist George Booth first began drawing. Since then, the 92-year-old artist has traveled from Korea to Chicago practicing his craft. These days, you’ll find him sketching on asphalt, at a Brooklyn block party, while Willow Smith’s “Whip My Hair” blasts in the background.

Now in his fifth decade as a contributing cartoonist at The New Yorker magazine, Booth claims Crown Heights as his home. The artist moved in with his daughter, Sarah Booth, 50, five years ago after a two-week hospital stay. For George Booth, the neighborhood goes unmatched, even compared to the small Missouri town of 75 people, with a single wooden sidewalk and one general store, where he spent his childhood.

“Well, if it’s any help to you, I’ve fallen in love with Brooklyn,” he said. “Other places don’t function as a whole unit,” adding that “everyone in Brooklyn knows what to do with themselves.”

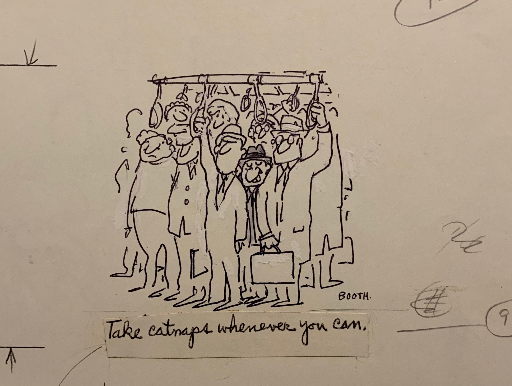

That includes him, as is evident in watching him spend time at a Crown Heights favorite pastime: the block party. On hands and knees, using only a piece of chalk and the city as his canvas, Booth introduces a new generation to his drawings of rabbits, dogs, and even “rabbit-dogs.”

“Makes them feel closer to life,” he says of the pre- and grade-schoolers who usually join in after looking on, then adds, “Makes me feel good.”

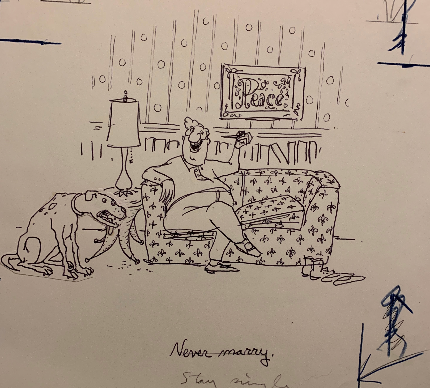

As for the animals? If you ask the artist why he’s incorporated the two- or four-legged creatures in many of his drawings, he’ll tell you “they’re fascinating” and that dogs are in on everything.

“If you go through a dog’s mind, you get a better viewpoint,” he said.

Booth began drawing at the age of three. By 1944, he was living in Fairfax, MI, when he was drafted by the Marine Corps. Within two years, he began working at an official Marine Corps publication.

“When it came time for me to be discharged they offered me an opportunity to go to Washington DC and cartoon with Leatherneck [magazine],” Booth said. “So I reenlisted.”

That was 1946 when he and illustrator John DeGrasse worked in the back of a brownstone, two blocks East of the White House. Booth had specific instructions to write for the infantrymen, a tall order considering he had no combat experience. By 1952, he’d made his way to New York, but not Brooklyn.

“I was in Whitestone and I heard about Brooklyn and how they were machine gunning each other over here and I swore I didn’t ever want to go around Brooklyn,” Booth said. That sentiment would change.

By 1965, the cartoonist was making a name for himself along the freelance circuit, with work in the Saturday Evening Post, The American Legion, Look and Collier’s. To hear him tell, it was a rootless existence.

“I just moved my stuff around town once a week,” he said. “Everybody did that.”

Several years later he’d sell his first cartoon to The New Yorker in 1969, the publication he’d come to learn is the “pinnacle of the trade.” Booth has since contributed hundreds of cartoons, with well over a dozen covers to the magazine while publishing several children’s books along the way.

And now, at yet another chapter in his life, the working cartoonist sees the world through another lens. This is different from the sidelines of WWII, the Korean War or Long Island where he used to live with his wife Dione Rankin. It’s a perspective that paints the extended family as those you see every day — your neighbors.

“It’s a comfort to me to know who I’m drawing for,” said Booth of how the borough has shaped some of his recent pieces. “If I think about families in Brooklyn, that helps me a bit.”

Since moving to Lincoln Place (near Brooklyn Avenue) his role as “Mr. George” comes with a different kind of celebrity. People know him as the man who walks his daughter to the Kingston Avenue train station every morning. It’s then, he stops to talk to Brooklyn stoop dwellers, always eager for a morning chat.

He’s the guy they have over for Thanksgiving dinner and check-in on from time to time.

All of which makes for good camaraderie and excellent material. As does the annual West Indian American Day Parade which runs along Eastern Parkway, a block away from his home.

“It’s unity in action,” he said of the festival that brings tens of thousands to Central Brooklyn. “Everybody’s involved, everybody knows what to do. Once in a while, someone gets in my way,” he joked while making nudging motions.

When asked to name the piece of which he’s most proud, he quips, “I don’t know if I can pin that down because I’m all out of proportion with pride.” But he admits that human interest topics are his favorite because “more people understand what you’re drawing and what you’re talking about.”

After a two-hour interview, Booth, who celebrates his 93rd birthday this June, put on his brown leather jacket accompanied me down two flights of stairs and walked me to my car, all the while reflecting on his life’s span of work.

“I’m grateful for my age and I will continue, but my jokes probably won’t be any better,” he said.