What’s A Fair Fare? Part 1 Of 3 – The History Of Free Transfers

THE COMMUTE: Next to providing air conditioning on the subways and buses, the second greatest advancement made by the MTA/New York City Transit Authority was to provide free bus transfers throughout the system. Providing transfers between buses and subways comes in third and unlimited ride cards fourth, in my opinion. Even with all these advancements we still do not have a fare that is fair for everyone. If your trip requires more than two buses you must pay a second fare, but the number of subway trains you can take for one fare is unlimited.

Why should that be the case? Shouldn’t it be guaranteed that your trip within the city cost you only one fare, regardless of the number of vehicles required, or your fare determined by some other rational means? After all, you are not getting better service for the extra fare you pay. In fact you are already being penalized with additional wait times for that third bus. An extra fare would only make sense if you were being provided with extra service, because you are making an unusual trip and it is costing the MTA extra to provide that service to you. That is not the case. You require a third bus in most cases because of deficiencies in the routing system, which don’t permit you to complete your trip using two buses, or a bus and trains(s). That is not your fault — yet you are penalized for system inadequacies.

It Used To Be Much Worse

When I was growing up in the 1950s, my father would routinely make us walk a half-mile to take a bus when the closest one was less than a quarter of a mile away. He did this to save a fare, which was only 15 cents at the time. That seemed ridiculous to me on two levels. First, because the fare was only 15 cents, and second because I could not understand why a bus route would transfer to one route but not another. It wasn’t ridiculous to him, however. An extra fare raised the cost of a round trip to the beach from $1.20 to $2.40 for a family of four, and when you have to support a family on an annual income of $3,000 to $4,000 a year, every penny saved did, indeed, count.

As I grew up, I learned that the subway system was formerly operated by two private companies — the IRT, BMT, and by the city, which called its system the IND. Also, that the bus and trolley lines were once operated by the BMT and, before that, by private companies. Each company was competing for the same clientele before being taken over by the New York City Board of Transportation in 1940, and later by the New York City Transit Authority in 1953, which also operated most all buses in Brooklyn.

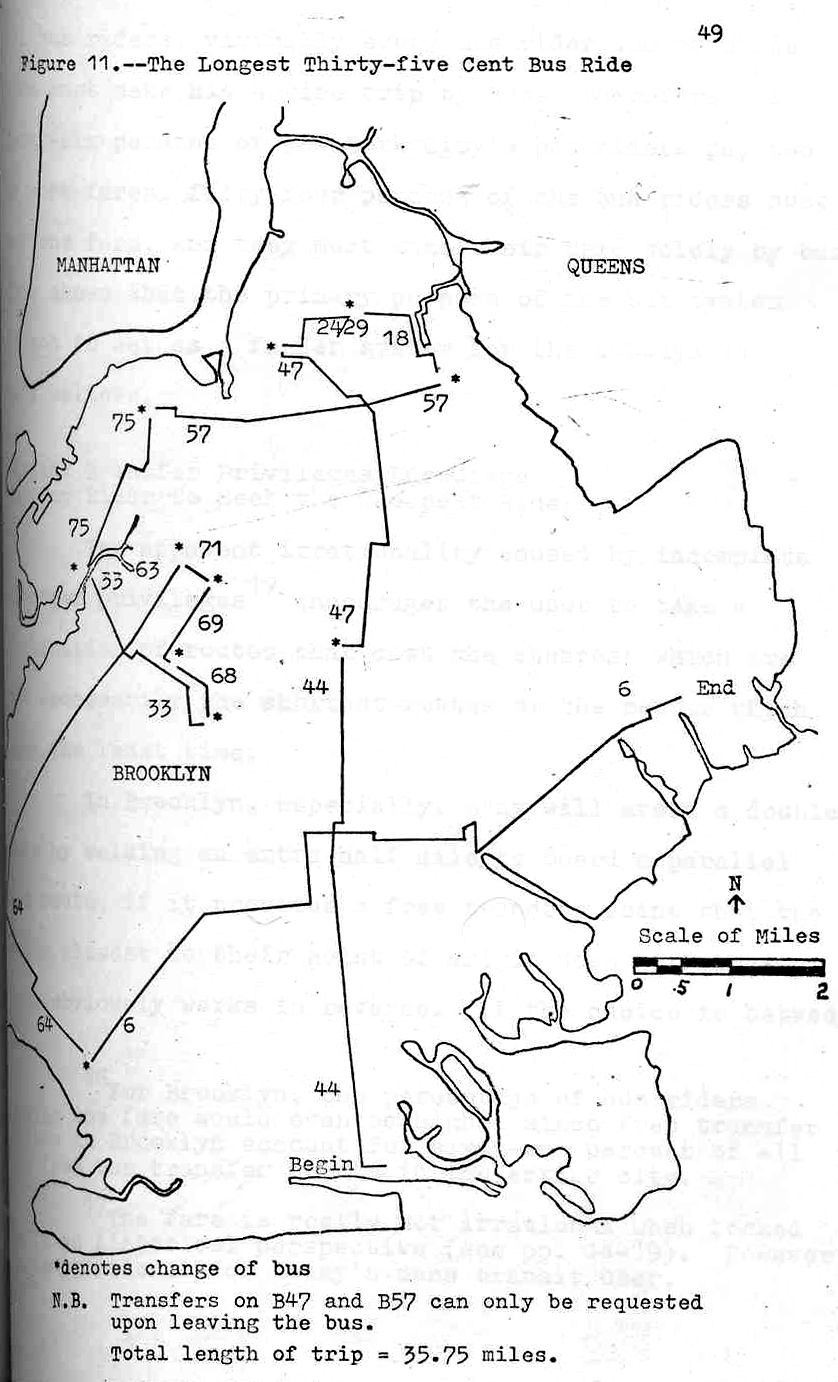

When all routes were privately operated, there were few if any transfers between divisions of the subway. Transfers between different bus companies only existed when it was considered to be beneficial for both companies. To make matters even more confusing, sometimes you could transfer from a northbound route, for example, to travel east, but it would cost you an extra fare to travel west on the same bus route. [See above map from my 1975-1978 Department of City Planning Bus Study.]

If a route operated only during the summer, or was discontinued, a three-legged transfer would permit you to ride a third bus for a single fare. No one would have to pay an extra fare as a result of a service discontinuation. That part was logical. Usually free transfers were given when you boarded the bus, but in some locations, such as at the Williamsburg Bridge, everyone was entitled to a free transfer upon getting off the bus… even if you boarded with a free transfer.

If this wasn’t complicated enough, in 1962, the private bus companies in Manhattan and the Bronx folded and were taken over by a newly-created subsidiary of the New York City Transit Authority (NYCTA) called the Manhattan and Bronx Surface Transit Operating Authority (MaBSTOA). As part of the agreement for city takeover, virtually all bus transfers in Manhattan and The Bronx were eliminated. Therefore, every time you needed to change for a different bus, it would cost you an additional fare. By comparison, we in Brooklyn — where the free transfers that existed were maintained — were lucky.

Subway Bias

When the subway system was unified under the Board of Transportation in 1940, measures were immediately taken to create underground free transfers between the three divisions. These did not appear overnight, however. During my lifetime I remember free transfers created at the Atlantic Avenue complex and at 14th Street between Seventh Avenue and Eighth Avenue to name two. More recently, free transfers were created in Long Island City between the G and E lines, and a long-needed free transfer was created between the Jay Street and Lawrence Street stations, now known as Jay Street-Metrotech. Another free transfer at Broadway-Lafayette Street and the Bleecker Street platform northbound is due to open this month. These efforts were all undertaken to increase the flexibility and usage of the subway system.

However, for buses, it was quite another story. Before the introduction of free bus transfers system-wide in 1994 within the NYCTA / MaBSTOA family of routes in 1981, any bus route that was instituted or extended after the 1953 creation of the New York City Transit Authority offered no free transfers on that portion of the route. Double fares were required until September 1975, when Add-A-Rides provided some temporary relief to the double fare by allowing a second fare for the price of a half fare, or 25 cents.

The payment of an additional fare or half fare reduced the usage of new routes and extensions. For example, the B78 (now the B47) on Ralph Avenue was created around 1966. If you lived midway between Utica Avenue and Ralph Avenue, which route would you use if you required a transfer — the one offering them for free or the route that required a double fare an additional charge? Many would walk extra just for the free transfer. That practice made trips take longer and overcrowded some routes unnecessarily.

Change Takes A Long Time

For as long as I can remember, I was always interested in maps and subways. However, it was this crazy transfer system that first got me interested in buses. It took me years to realize that the transfers, as well as the routes, were both accidents of history and that neither of them was planned. After all, who would devise a system in which you are penalized if you used the most convenient bus line? In Manhattan, you were encouraged to use mass transit for the longer component of your trip (north/south, or east/west) and to walk the shorter component. Although the Brooklyn Queens Transit Corporation (BQT) and later the Brooklyn Manhattan Transit Corporation (BMT) absorbed all the privately-operated bus lines in Brooklyn before World War II, they never changed the transfer policy to allow transfers between all routes. Worse yet, the NYCTA, in 1953, also retained this same transfer policy from the 1920s and 1930s.

Add-A-Rides did nothing, however, to provide any rationality to New York City’s fare policy. In 1972, when I needed a topic for my Masters Thesis in Urban Planning, a further investigation of the bus system in Brooklyn provided me with the means to satisfy my curiosity to study the history of the bus routes and the transfer system. I devoted an entire chapter to the absurdity of the fare and transfer system, describing in detail how, by connecting the three-legged transfers that were in place, you were allowed to take as many as 14 consecutive buses on a single fare, when most two bus trips required additional fares. I even dedicated my thesis to “all the other New Yorkers who walk a half mile or more every day to avoid paying a double fare.”

Although 1981 was the pivotal year in rationalizing the transfer policy, it was not until 1993 that routes operated by private companies allowed free transfers between companies and to and from NYCTA / MaBSTOA routes. Even then severe restrictions were placed on the new transfers offered. They were not permitted with intersecting routes at a terminus or within ¾ mile of a terminus. Two bus trips for one fare, everywhere, were not allowed until MetroCard Gold was introduced in 1994 1997 when paper transfers listing routes where transfers were permitted were replaced with MetroCard transfers to the bus and subway. This finally ended the irrational bus transfer system, in place since before 1940.

Next Week: Are we moving backwards, and how the introduction of Limited Stop Service and Select Bus Service are also necessitating double-fares or longer walks.

The Commute is a weekly feature highlighting news and information about the city’s mass transit system and transportation infrastructure. It is written by Allan Rosen, a Manhattan Beach resident and former Director of MTA/NYC Transit Bus Planning (1981).

Disclaimer: The above is an opinion column and may not represent the thoughts or position of Sheepshead Bites. Based upon their expertise in their respective fields, our columnists are responsible for fact-checking their own work, and their submissions are edited only for length, grammar and clarity. If you would like to submit an opinion piece or become a regularly featured contributor, please e-mail nberke [at] sheepsheadbites [dot] com.

Correction (8/14/2012 at 1:46 p.m.): Both references to 1993 have been changed to 1994. We apologize for any confusion.

Clarification (9/4/2012): The author of the article requested permission to make edits and clarifications to the above post. The content remains largely the same, though some paragraphs have been restructured. In the instances where the author sought to correct factual information within the article, we have included the original information with a strikethrough to indicate the correction.