As Vote On Tax Break For Developers Approaches, Some Tenants Call Foul

Tenants groups and some local officials are asking the state and city to think twice before they renew a long-standing tax credit for developers.

Community-based organizations, including the Flatbush Tenant Coalition, rallied outside of City Hall Thursday, December 1, urging the de Blasio administration not to reinstate the 421-a tax credit program, which provides housing developers with a major reduction in their New York City property taxes. The program expired last year, but is back in play now that the Real Estate Board of New York and city construction unions have reached an agreement on wage levels for construction projects that get the tax credit.

Renewal of the tax credit requires approval from the state legislature, which, according to some news reports, may return to Albany for a special session this week. The 421-a program is believed to be one of the items on their agenda.

Until the program expired last year, qualifying developers could obtain an exemption for up to 25 years from the increase in real estate taxes that would have normally resulted from their new development. In exchange for the credit, developments in some areas, including Manhattan and sections of Brooklyn, must provide some affordable housing — at least twenty percent of units.

There is no affordable housing requirement for developments in our area that benefit from the 421-a tax credit.

The 421-a program is New York City’s largest tax expenditure, the Center for New York City Law reported last week. “In fiscal year 2015 the program cost the City $1.2 billion in foregone property tax revenue.”

The deal reached last month could increase the length of the property tax exemption to 35 years. It would also increase the number of years that any new affordable rental units must remain rent stabilized, from 35 to 40 years. Under the existing 421-a guidelines, all market rate rental units also become subject to rent stabilization, for the duration of the benefits.

Groups protesting renewal of the tax credit on Thursday were joined by a handful of City Councilmembers, including Jumaane Williams, who told us that the “421-a [tax credit] never operated the way people expected it to. We didn’t get the number of affordable units we expected.”

In 2014, the Manhattan Borough President’s office estimated that only 14 percent of all 421-a tax-exempt units are affordable to lower income households. “The impact of 421-a on new construction of affordable housing…remains minimal,” the BP’s office maintained.

Ruth Riddick, a member of the Flatbush Tenant Coalition, told us that she was at Thursday’s rally to fight against renewal of the tax abatement, which “will take money from the City…that could go for affordable housing, and to fight for better rent laws.”

Riddick pointed to the over 62,000 homeless New Yorkers in city shelters this week, many of them children, who are waiting for permanent, affordable housing.

Councilmember Williams agreed, saying that If the City is serious about getting private sector developers to build affordable housing, it should offer direct subsidies, not tax breaks. Williams has been joined by Councilmember Brad Lander in arguing that the 421-a tax credit benefits large developers and has paved the way for rapid gentrification across the city. See where other local lawmakers stand on 421-a here.

At least some affordable housing developers maintain that 421-a has been critical to making low to moderate rental property development feasible in New York’s over-heated market. Forty-two percent, or 5,885 of the 13,755 affordable units built in New York City in 2014 and 2015, were facilitated by 421-a tax breaks, Curbed reported in May.

Curbed also reported that construction applications for new residential developments “plummeted” in 2016 after the 421-a program expired. Councilmember Williams disputed this, telling us that “[construction] permits are coming in — without 421-a.”

Another issue raised by critics of 421-a is whether developers are complying with the program’s requirement that affordable units be designated with the State as “rent-stabilized.”

An analysis by Pro Publica in October found that two-thirds of the 6,000-plus rental properties receiving tax benefits from the 421-a program “don’t have approved [421-a] applications on file and most haven’t registered apartments for rent stabilization as required by law.”

In response, Council Member Williams has introduced a bill requiring the City’s Department of Housing Preservation and Development (HPD) to audit a set number of buildings receiving 421-a benefits every year in order to “ensure compliance with rent registration requirements.”

A separate bill, sponsored by Council Member Stephen Levin, would require HPD to audit buildings receiving 421-a benefits to ensure compliance with affordability requirements.

And Public Advocate Letitia James has sponsored legislation that would require HPD to “expand its existing online property owner database to include information on each registered dwelling’s owner, outstanding notices of violation, list of tenant complaints and pending tax liens.”

The de Blasio administration reportedly supports efforts to tighten enforcement of the program.

The 421-a program was originally launched in 1971 to stimulate housing development in New York City, which was struggling with population loss and private sector disinvestment at the time. As property values recovered and construction surged after the 1970s, the program was modified in order to extract some affordable housing from development in certain neighborhoods.

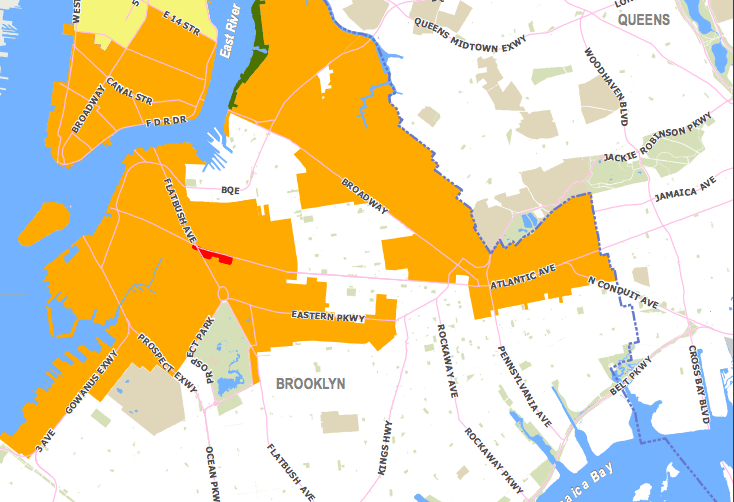

In Brooklyn, the 421-a affordable housing requirement now applies to downtown Brooklyn, as well as portions of Fort Greene, Red Hook, Sunset Park, Prospect Heights, Park Slope, Carroll Gardens, Cobble Hill, Boerum Hill, East Williamsburg, Bushwick, East New York, Crown Heights, Weeksville, Highland Park, and Ocean Hill.

The orange shading in the map below shows the sections of Brooklyn with an affordable housing requirement for developers who use 421-a.

The red sliver off Flatbush Avenue is the Atlantic Yards Arena Project, which has “special” affordable housing provisions. The Greenpoint-Williamsburg waterfront also has a “separate Waterfront Exclusion Area in effect since 2005, with different affordability requirements.”