Unapologetically Black Celebration of Black Writers And The Space They Make

CROWN HEIGHTS -There was standing room only in each of the sessions at the 2019 National Black Writers Conference Biennial Symposium, held yesterday at Medgar Evers College. The attendees were excited, engaged, and unapologetically black as they embraced the day’s special guests and speakers.

“I always feel extra black when I come here,” Jamal Joseph, playwright, director, and producer announced to a delighted audience before his panel discussion “Interdisciplinary Perspectives on Contemporary Plays by Black Writers: From the Page to the Stage and Screen.”

Scholars, students, writers, aspiring writers, playwrights, directors, producers, and many other supporters of the arts, came out to what some called a celebration of black writers.

The symposium’s theme, “Playwrights and Screenwriters at the Crossroads,” gave playwrights and screenwriters the opportunity to discuss the challenges and triumphs black artists are currently facing or embracing in the movie, TV, and theater industries.

But the common conversational thread in the panel discussions and town hall forum was how black artists can and will continue to occupy spaces once only open to Caucasians. Creating space in a closely guarded industry is something the symposium’s honoree, the late Ntozake Shange, did well.

Shange is best known for the play, “for colored girls who have considered suicide / when the rainbow is enuf,” which premiered in 1976 at the Booth Theatre in New York. The play was a combination of poetry, dance, and music which Shange called a choreopoem, a term she coined in 1975.

Shange’s presence permeated the symposium.

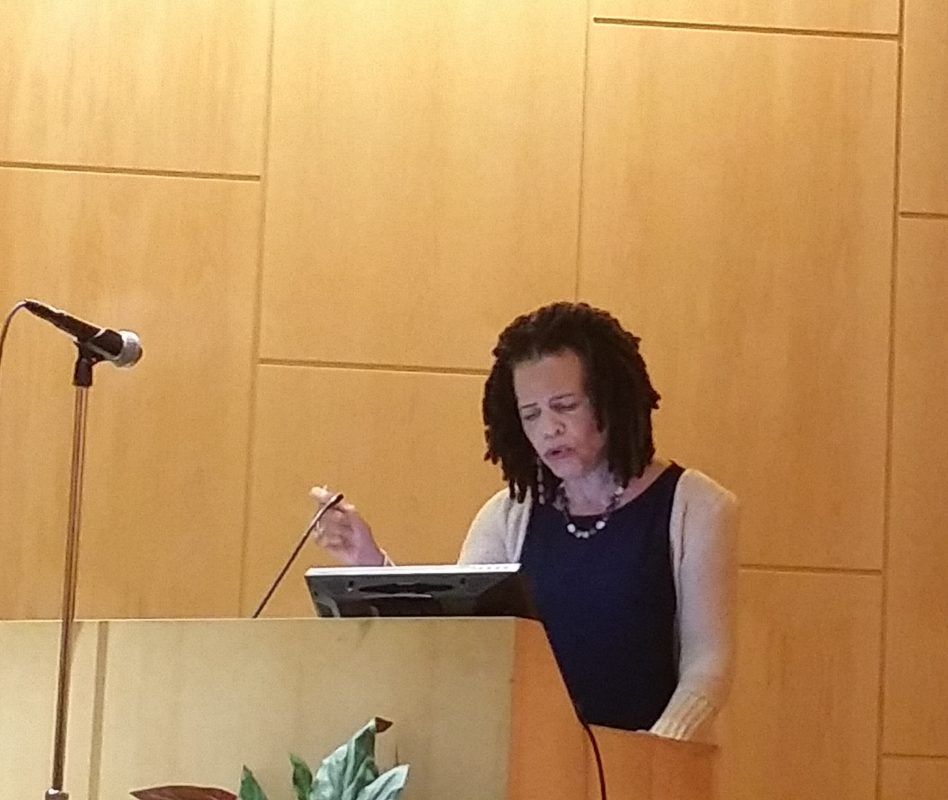

Medgar Evers College student and spoken word artist Kimberly Powell gave a strong rendition of two excerpts from Shange’s “for colored girls.” Dr. Brenda Greene, executive director of the Center for Black Literature and the National Black Writers Conference discussed with panelists Joseph, Ladee Hubbard, and Gloria J. Browne-Marshall how movement – a staple in Shange’s work – play a role in writing. Distinguished playwright, producer, and novelist Ifa Bayeza’s keynote address on Shange read more like a performance piece than a speech, moved many in the audience to tears.

Bayeza remained composed but made it clear before she started that speaking about her sister, whom she had a close but complex relationship with, would be difficult. She not only gave an intimate, convoluted, and truthful story of her sister, Bayeza’s reflection also showed just how unafraid and intentional Shange was in letting her blackness fill the spaces she was in.

“I chose this occasion, the national black writers conference at Medgar Evers College in [Shange’s] beloved Brooklyn, to attempt to contemplate the legacy of my sister,” Bayeza started. “A writers conference honoring writers. A black writers conference celebrating the voices of the diaspora. This is the perfect place to remember and to champion all of those elements that Zake represented: writers, writing, blackness, womanhood.”

Bayeza painted strong imagery of what it was like for her sister, as well as herself, as Shange struggled and thrived almost concomitantly while living with bipolar disorder. This contributed to Shange’s genius and her life tribulations.

Walker Sands, an emerging novelist and poet, came all the way from Washington, D.C. for the symposium to “bring out the writer” in him. Bayeza’s speech moved him.

“She gave a full picture of an artist and spoke openly about her sister’s work and struggle and where those two things met,” Sands said. “She saw where that art came from and still celebrated her as a big sister.”

Bayeza told the Bklner when Dr. Greene extended the invitation to her last December to give the keynote for her sister’s tribute at this symposium, she knew she would be ready and this would be the perfect venue.

“[When Shange died] I was getting all of these notices, announcements, and requests – a lot of people were doing memorials without contacting the family – because she was a public persona and so well-loved and I understood that. But I was being barraged by people wanting me to weigh in and participate in some way. That was way early,” she said. “When Dr. Greene called I said the NBWC already had something that was part of their program in celebrating one black writer every year. And so this was the best platform.”

The March date gave her enough time to “center myself and gather my thoughts to talk about my experience with Zake as a writer.” That experience spanned from when she was first impressed by a 7-year-old Shange’s command of writing her own name with great flair and rhythmic movement to how endearing it was to see Shange’s repetitive attempts at practicing to write her name again at age 70 after a number of ailments took away her ability to use her hands.

According to Dr. Greene, the words of Shange and August Wilson were the catalyst for the goals of the symposium, “to provide a forum for black playwrights and screenwriters to meet face to face and showcase and examine the trends and themes in their work.” This was the first time the NBWC focused on playwrights and screenwriters at either of their conferences or symposiums. Next year they will expand this new but salient area into a four-day conference.

Other black artist participants for the day included Attika J. Torrence, the “Rest in Power: The Trayvon Martin Story” co-producer who is working on a feature film; Lisa Coates whose documentary on the Apollo Theater will be the opening night film at the Tribeca Film Festival; Kamilah Forbes, Tai Allen and more.

Emerging artists like Sands reveled in the idea that an event such as the NBWC symposium supports the artistic journey of black artists making their stories a reality and sharing them with the world. “Anything that can celebrate the uplifting of that must be a good experience and it’s true. This [symposium] has really been a good experience.”