Teknopolis brings VR, Interactive Art, and Singing Clones to BAM

On Saturday, inside an exhibition hall at BAM Fisher, Lieven van Velthoven reached up over his head, grabbed a beam of light that was projected onto the wall behind him and handed it to an excited 6-year-old boy. The boy giggled as the light started to grow over him and he placed it down lower on the wall where it spread out in tendrils like a vine.

Van Velthoven, a digital artist from the Netherlands with a tall, skinny frame and a broad smile was showing off his project “Virtual Growth.”

“It should be called virtual overgrowth, I guess,” he said, as the projections formed patterns on the wall. “Someone referred to it as virtual fungus, which I thought was hilarious, but quite fitting.”

Virtual Growth occupies just one corner of a building full of interactive artworks and virtual reality experiences that make up BAM’s annual Teknopolis exhibit. This year’s show, which runs through March 8, turns BAM Fisher into Brooklyn’s coolest toybox.

Every part of Teknopolis is meant to be explored, poked or generally fooled-around-with. Upstairs there are VR headsets that can introduce you to alien dinosaurs or drop you into the middle of a 360-degree movie. Downstairs, visitors can conduct a virtual choir, project lasers into hypnotic patters across the room or rock out on a household broom that magically replicates a guitar. The whole point of the show is to encourage visitors to let their guard down and have fun.

“I know things are going well when it’s hard to tell the difference between the kids and the adults,” says Steven McIntosh, BAM’s director of education and family programming, who curated the show. “We want our community–no matter what their background or experience level– to come in and play. We believe that everyone is an artist.”

For McIntosh, the best thing about interactive art is how it turns the audience into collaborators in the artistic process, even if they don’t realize it. “If a person is actively engaged with the art,” he says, “it gives them more opportunity to make connections within themselves.”

In other words, the act of play can lead to cool moments of creativity for kids and adults alike.

Christopher Short is the artist behind “Ghost Sine” a hypnotic laser projection mounted high in the rafters that visitors can control via an iPad. On Saturday, Short stood to one side and smiled as a small group of kids noodled with the controls.

“Seeing these kids grab the panel and move all the sliders all the way up and then slowly move them down and start to figure it out—to me we’ve made a connection in their brain,” he said. “It doesn’t need to be hard, it doesn’t need to be complicated, it just needs to be fun.”

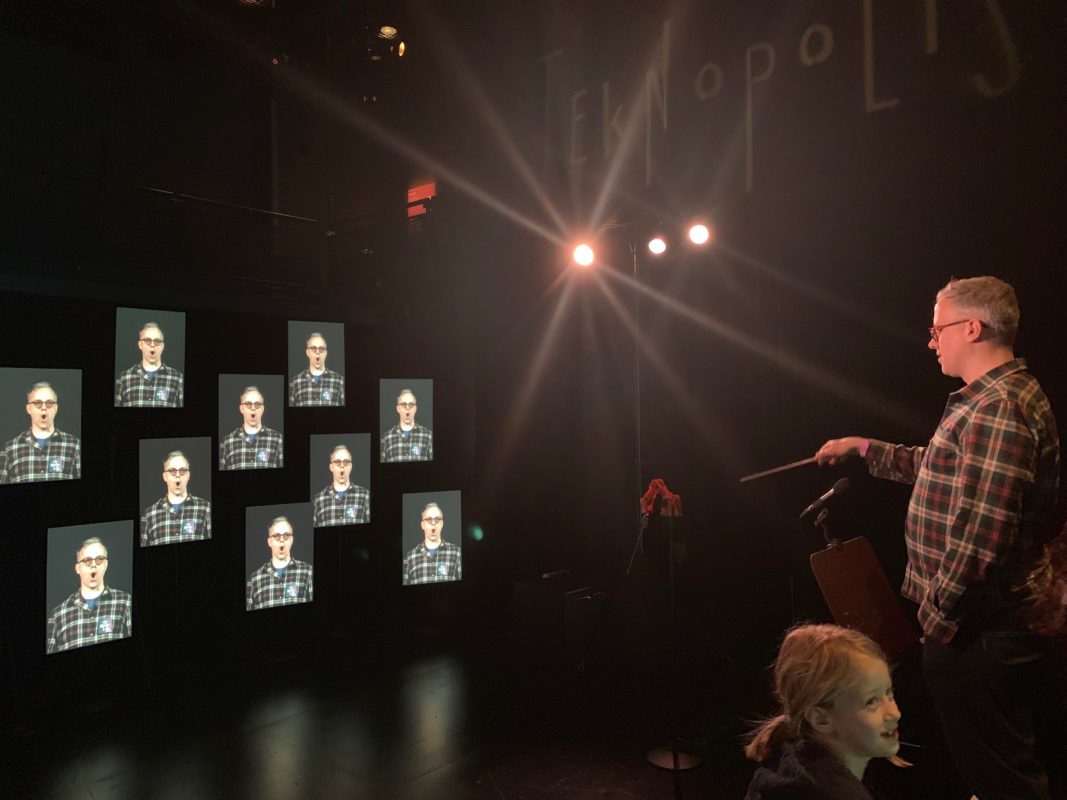

Down on the exhibit floor, a girl giggled as her father tried out “SMing,” an array of screens set in front of a conductor’s podium. Her dad had climbed the podium, grabbed the baton and was now conducting a chorus of singing clones of himself. This was a side of her father that the girl hadn’t seen before, and she thought it was a riot.

“Some people are really shy and come into the experience really slowly, other people come with big movements and big sound,” said Gaetan Libertiaux, head of Superbe, the Belgian studio behind SMing. “There’s always some kind of personality that expresses itself in the music.”

It’s that contribution from the audience that makes interactive art so exciting for the artists.

“Interactive art can’t be finished, it can only be prepared,” says Ryan Edwards, a creative director, and composer at the Boston-based Masary studios. Their work “Figuration” generates trippy visual effects and music in response to the movements of people in front of its screen. For Edwards, interactive art is never really complete until a real audience gets to experiment with it. “You can kind of set it up,” he says, “but it can’t be completed in a studio.”

Teknopolis runs at BAM Fisher Feb 27- March 8. Tickets at BAM.org