What To Know About The “Right To Know” Act

Last week, the city’s Right to Know Act went into effect, creating new rules to govern interactions between police and civilians in an effort to increase transparency.

The Act was sponsored by Councilmember Antonio Reynoso (D-34), who sponsored the bill, hoping to decrease the instances of civilians mistakenly consenting to searches during their interactions with police.

Reynoso has spoken about his own interactions with police as a young man of color and how they shaped his desire to reform civilian-police encounters and to limit unwarranted searches. Last week, after years of work, his team was on the streets with pamphlets to let residents know about the new law:

This morning, Team Reynoso, the CCRB, & @NYCProgressives members hit the streets to educate residents about the RTKA, which goes into effect TODAY. Thanks to everyone for their efforts, and visit https://t.co/7sLTL74z1R to learn more about how this will change policing in NYC. pic.twitter.com/y0pSIdk2oe

— Antonio Reynoso (@CMReynoso34) October 19, 2018

The Right to Know Act has seen some opposition, especially from the NYC Patrolmen’s Benevolent Association, which has alleged that the new law will escalate encounters between police and civilians.

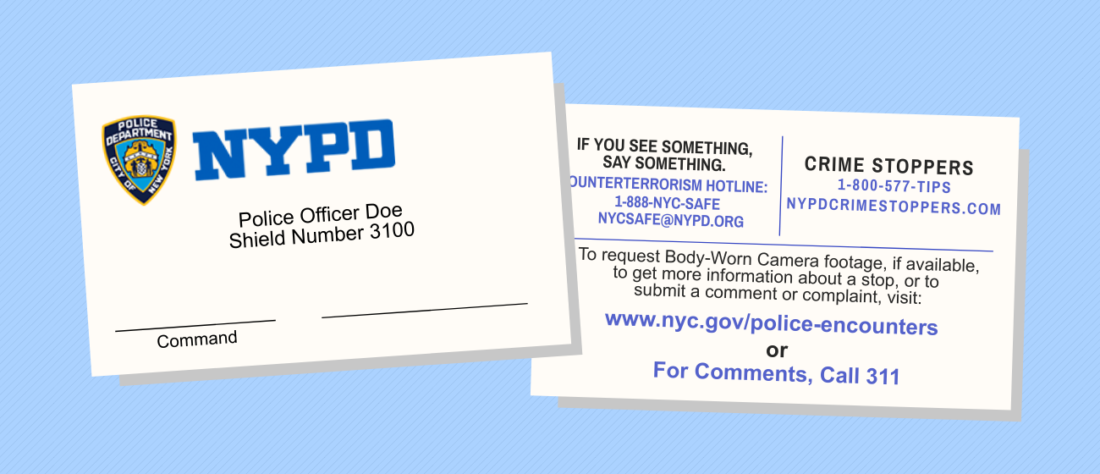

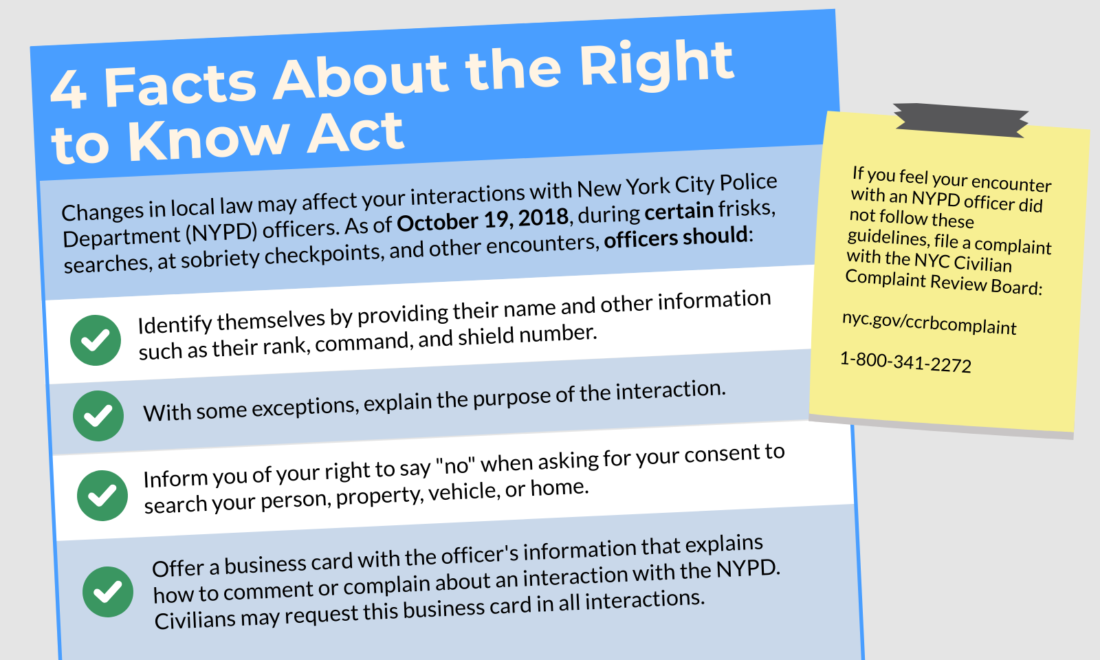

The first main component of the act dictates how police officers identify themselves to the public. With the law in effect, all officers will carry business cards that give their name, rank, precinct and shield number, along with information about how civilians may officially comment or complain about their interaction with the officer, as well as how to request body-cam footage of the encounter.

A key distinction is that while civilians are able to request the cards from officers at any time, officers are only required to offer it in certain cases. Examples of these include frisking, searches of a person, their property, vehicle, or home, and at sobriety checkpoints.

If an officer refuses to hand over their business card, civilians can make a complaint to the NYC Civilian Complaint Review Board.

The other major feature of the Right to Know Act comes into play when police officers want to make a search. When officers need consent to perform a search, whether on a person or on their property, home or vehicle, officers must first obtain consent—and record the consent on their body camera where applicable.

Importantly, officers must also inform civilians that they have the right to refuse consent to the search. However, this doesn’t apply to all situations. If an officer has a reasonable suspicion that the person they’ve stopped is armed and dangerous, they don’t need to obtain consent for a search.

Click here to view a pdf outlining Frequently Asked Questions about the Right to Know Act

The New York Civil Liberties Union is also hosting a Facebook Live Q&A session about the Right to Know Act:

TODAY: @msisitzky answers your questions about the Right to Know Act on Facebook Live. Submit your questions below and join us at 1pm at https://t.co/CkjkKbdXFc! #RightToKnowAct pic.twitter.com/Z1cGShHzOw

— NYCLU (@NYCLU) October 25, 2018