Residents Propose Bushwick Community Plan for Rezoning To Tame Development

BUSHWICK – After nearly four years, countless hours of meetings and deliberations, and some pushback from community activist groups, Bushwick officials and residents unveiled a long-awaited plan on Saturday to shore up the neighborhood against the effects of gentrification and development in the coming years.

The Bushwick Community Plan (BCP) is a collaborative framework that contains strategies for addressing a host of issues affecting the rapidly-gentrifying neighborhood, from zoning and land use to economic development and transportation. It takes specific aim at the former categories, proposing a downzoning across most of the district and an increase in affordable housing stock in a bid to moderate future growth and preserve the neighborhood’s existing character.

“The plan that I want to push is the plan that comes out of this,” Councilman Antonio Reynoso, who represents Bushwick as well as parts of Williamsburg, told residents at the release event over the weekend. “Not a plan that comes from the administration, not a plan that comes from [the Department of City Planning]. I want to make sure that we follow through on every aspect of this plan from the community. I want this to be the first community plan in the city of New York that’s done word-for-word.”

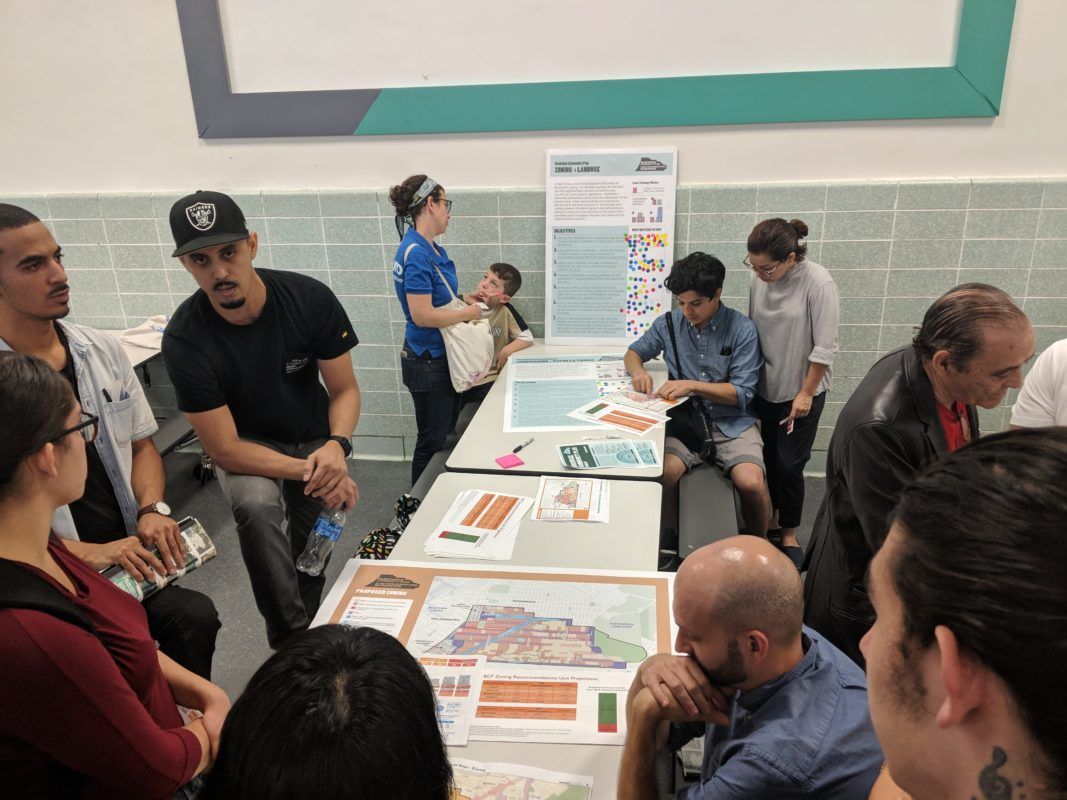

Details of the plan were presented in full at the town hall at Bushwick High School, where Reynoso and other stakeholders heralded it as one of the strongest examples of a community-based rezoning initiative in New York. Though other neighborhoods—such as East New York in 2015 and East Harlem in 2016—have relied on community input in their rezoning efforts in recent years, few have seen engagement as comprehensive as Bushwick’s, they said, which brought together a whole range of community stakeholders, including local civic groups, elected officials, and residents themselves.

Other elected officials present at the event included 7th district congresswoman Nydia Velázquez and 53rd district Assemblywoman Maritza Davila.

“This plan is really different than any rezoning plans that have been put forward before,” said Alex Fennell, the Network Director for the nonprofit Churches United For Fair Housing. “All of the previous rezonings, there was some public comment and some community engagement, but what makes Bushwick unique is that the community was engaged since day one and actually started the process. This is not a situation where the city is presenting us with a plan and we kind of take it or leave it.”

Bushwick’s own initiative was conceived in 2014, after members of its community board asked Reynoso’s and fellow councilman Rafael Espinal’s offices to conduct a study of out-of-context development occurring in the district. A predominantly working-class neighborhood with a large immigrant population, Bushwick has been at the forefront of the wider borough’s encroaching gentrification in recent years, with rents having increased 35 percent since 2010. Over half of households are burdened by high housing costs, meaning they spend more than 30 percent of their income on rent, and only a third of residents live in rent-stabilized housing.

New developments — 5,000 units since 2008, officials said — have sprung up across the district to alleviate that burden. But, thanks to a uniform zoning designation left in place since 1961, they’ve been built with little regard to size and without the kind of affordability guarantees intended to protect longtime and low-income residents from displacement, critics argue.

Officials and residents met at over a dozen meetings in the last few years to address those conditions, including at community-wide town halls and zoning workshops. Subcommittees were formed by the community board to formulate priorities on specific issues, such as transportation and open space. A steering committee to oversee the process was also convened, featuring representatives from a number of local organizations and nonprofits, like Make The Road New York, Riseboro Community Partnership, and the North Brooklyn Coalition.

The resulting plan puts forth a number of changes aimed at improving residents’ overall quality of life in the district. Some are targeted, such as better lighting in parks and increased sanitation funding for major thoroughfares, the institution of a flipping fee on speculators and creation of a tax credit program for landlords of small homes, or the establishment of historic corridors along streets like Bushwick Avenue.

Others, however, are more sweeping. Among the plan’s more significant proposals is a rezoning of major parts of the district, including a downzoning of many residential sidestreets from the current R6 designation and a higher density upzoning of major transit corridors like Myrtle and Wyckoff. Such changes would impose height and scale regulations on new developments, which officials said would prevent the kind of out-of-character buildings that have arisen in recent years.

On housing, the plan also calls for a larger percentage of affordable units be built than required under the city’s mandatory inclusionary housing program, using public financing and tax credits to further incentivize developers. Framers said that would help ensure the neighborhood remains affordable to current residents even as development continues.

“We wanted to create a scenario where no more units would be built than under a no-action scenario,” said Scott Short, the chief executive officer at Risboro, who noted that as many as 7,000 market-rate housing units could result from Bushwick’s current zoning in the next year. “However, a significant portion of the units that would get built would need to be affordable.”

Residents and officials touted these measures and more at Saturday’s town hall, saying that they promised to inject the community’s voice into the city’s zoning deliberations. Framers of the BCP have criticized the Department of City Planning’s own plans for the district, arguing that they fail to take into account community-specific concerns, such as a commitment to deeply affordable housing and the preservation of Bushwick’s existing manufacturing spaces, half of which the city has sought to convert to residential housing.

They said the next step is to take the plan to the DCP, though it’s unclear how many of its proposals will be accepted.

“The city gave us their plan, it didn’t work, so we created our own,” said Robert Camacho, a longtime Bushwick resident who was recently elected chairman of Community Board 4. “And we got more affordable housing, more stuff. So we actually did the city’s job. Just do what we tell you to do, and keep the people here that fought to be here when nobody wanted to be here.”

Despite seeing widespread participation from residents, the BCP did receive some pushback from members of the community over the course of the planning process, in particular from anti-gentrification activist groups that have rejected all proposed rezonings of the neighborhood. The groups, including Mi Casa No Es Su Casa, have staged several protests around Bushwick over the last few months and broke up a community board meeting back in June.

“These plans never go through as the community truly wants them to,” said Bruno Daniel Garcia, a community activist with Mi Casa No Es Su Casa and a former member of the BCP’s steering committee. “Look at Inwood and East Harlem — in the final result everyone was like, ‘this is not what we wanted. We shouldn’t have participated in them at all.’ There’s no evidence or mechanism in place now that makes me think this will be any different.”

“It’s good that this process is engaging the community, but it’s almost co-opting community engagement and just using that as a rubber stamp for what’s going on,” he added.