Orthodox Women Rally to Break the Chains of Unwanted Marriage, Using Social Media As a Bolt Cutter

Chava Sharabani and her husband Naftali were legally divorced over a decade ago. But the marriage still follows her wherever she goes.

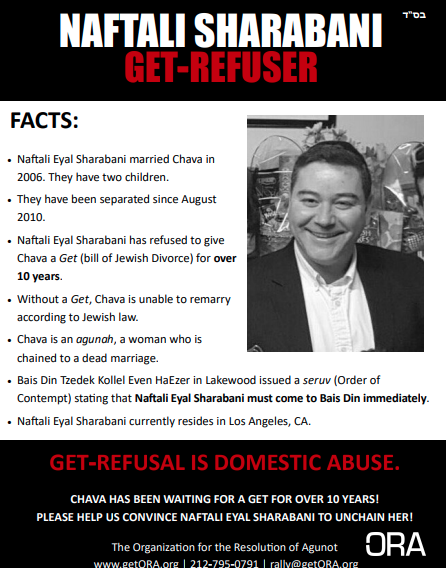

That’s because Sharabani, an Orthodox Jewish woman who lives in Midwood, has been unable to attain a “get,” a Jewish divorce contract, from Naftali. Jewish law requires both partners to consent to the divorce. But for over ten years, Naftali, who now lives in Los Angeles, has refused to sign the contract, leaving Sharabani alone to raise their two children and unable to remarry.

The plight of “agunot,” a Hebrew word used to refer to women “chained” to dead marriages, has existed for decades, even as activists have labelled get-refusal a form of domestic abuse. But in recent weeks, the issue has taken on renewed urgency, as Orthodox women have used social media to spur a wave of protests and activism that has, in multiple instances, successfully pressured get-refusing men to finally agree to a Jewish divorce.

The wave started when Dalia Oziel, a Jerusalem-based singer-songwriter, got wind of Sharabani’s plight. She created an Instagram page called The Get Busters, and began using the hashtag #FreeChava to generate awareness and financial support for the case.

Online engagement quickly snowballed, and other long-standing cases of get-refusal came to light. Social media posts led to street protests, and in recent weeks, there have been rallies throughout Jewish Brooklyn, led almost entirely by women, that seek to pressure rabbinic authorities to take action and negotiate a resolution case-by-case.

“It was an awakening and reckoning,” said Adina Miles-Sash, a Brooklyn-based activist and social media influencer known for her moniker FlatbushGirl, who has participated in several protests. “We were like, how have we not helped these women out, and how can social media be used to bring more awareness?”

Men refuse to grant gets for a variety of reasons. Sometimes, the get is used as leverage during civil court proceedings, to ensure the man is granted more favorable custody rights, financial benefits or other privileges.

“It’s very common for people to essentially immediately relitigate a divorce using a get,” said Keshet Starr, CEO of the Organization for the Resolution of Agunot (ORA), which provides education and support services to agunot. “They will walk out of divorce court, use whatever the order was a starting point, and then if you want your get, you’re going to agree to A, B, C and D.”

But the protests have resulted in some recent victories. Yesterday, the new outlet Vos Iz Neias reported that Jeff Hafif, a Flatbush man who was recently arrested on domestic abuse charges and who withheld a get from his first wife Evet for 17 years despite marrying another woman, had agreed to consent to the divorce.

Another woman, identified by Vos Iz Neias as Elizabeth K., also received a get after four years of waiting, largely thanks to pressure from activists.

The victories tend to follow a similar pattern. Rabbis and other community leaders start with gentle nudging and facilitated negotiations between the separated couple. If that fails, women must often resort to public pressure. A beth din (rabbinical court) may issue a seruv, a sort of contempt-of-court order that can be used to ban the get-refuser from Jewish communal life.

Nonprofit advocacy groups like ORA also launch public shaming campaigns to raise awareness of bad actors.

ORA says it has resolved over 330 outstanding cases through a combination of education, mediation and advocacy. Still, those victories are individual, not systemic, and some activists have begun to look for systemic solutions to the underlying problem.

ORA encourages couples to sign a “halachic prenup,” a legal agreement in which spouses agree to appear before a specific beit din and abide by its get decision should the marriage end in divorce. Many such prenups also include financial incentives that are enforceable in civil court.

“What it effectively does is allows us to have the enforcement power of the civil system, with the religious sensitivity of adjudication of the religious court,” Starr said.

Others have looked for legislative solutions. A bill introduced in the New York State Assembly, for example, would make “coercive control,” in which a person that engages in conduct that limits a family member’s “behavior, movement, associations or access to or use of his or her own finances or financial information,” a class E felony.

“The purpose of this legislation is to prevent an individual from exerting power over an intimate partner – or any household member – through non-consented use of a victim’s finances or financial information,” Queens Assemblymember Andrew Hevesi, the bill’s sponsor, told Bklyner. “By holding perpetrators accountable, we can begin to eliminate coercive control in all of its manifestations, and provide safety for any children or families that might otherwise experience this type of abuse.”

Though the legislation wasn’t created solely to deal with agunot disputes, similar legislation has been used to adjudicate such cases in the United Kingdom.

Amber Adler, a southern Brooklyn City Council candidate who has been active at several protests, believes the same could be true in New York, and is seeking to generate support for Hevesi’s bill amongst Brooklyn’s Orthodox communities, which have often been reluctant to allow state intervention in religious matters.

“The bill is speaking to women who are victims of abuse,” said Adler, a single mother of two who said she herself had struggled with a get refusal. “It’s a bill that gives you a tool. How you choose to use that tool is up to you. I think it’s important to always have access to resources and tools. People can speak with religious leaders if they know something is available.”

In the meantime, the agunot protests will likely continue, and many hope they will spur more lasting change.

“There’s more pressure not only on the man to give the document, but also on rabbinical leaders who are realizing they were asleep at the wheel and not advocating hard enough,” said Miles-Sash.

While rabbinical courts are managed and run entirely by men, she said, “women are pushing ourselves in the spaces where we can. No one can kick us off the sidewalk, or off social media.”

“It’s really a women’s movement. And It’s incredible to see what women are doing in the spaces they have access to.”