A Grand Master In Park Slope: ]ames Nyoraku Schlefer

A Grand Master lives among us.

The Park Slope neighborhood is well-known for its breadth of artistic talent and historic knowledge. On Saturday, September 26, Brooklyn native and long-time resident ]ames Nyoraku Schlefer will be presenting the community with a performance focused around a fascinating instrument with a tradition dating back more than 800 years.

According to Schlefer, the shakuhachi is a Japanese bamboo flute, “the only instrument associated with the practice of Zen Buddhism. The music was originally performed by monks known as Komusô (‘Priests of Nothingness’) who wandered about Japan playing in exchange for food or alms.”

Schlefer, who has been granted the honor of Grand Master of the shakuhachi, will be performing along with his students at the Brooklyn Zen Center (505 Carroll Street between 3rd and 4th Avenues) on Saturday, September 26 at 7:30pm. There is a suggested donation of $15.

While Schlefer’s performances are internationally-renowned, he’s a neighbor who raised his family here, runs and cycles in Prospect Park, and teaches locally. We had a chance hear from him about the art of the shakuhachi, how he became a Grand Master, and, of course, what he likes to do in Park Slope.

PSS: How did you begin your study of the shakuhachi instrument?

]ames Nyoraku Schlefer: I began shakuhachi study in 1979 soon after hearing the instrument for the first time at a small concert in the famed Dakota Building. At the time I was working toward an advanced degree in musicology, and performing professionally as a freelance flute player. I was drawn to the sound of the instrument and soon found a teacher in New York with whom I studied for several years, earning my first certificate of Jun-Shi-Han.

What are some the unique challenges of playing the shakuhachi? How do you incorporate the traditions and rituals when teaching it?

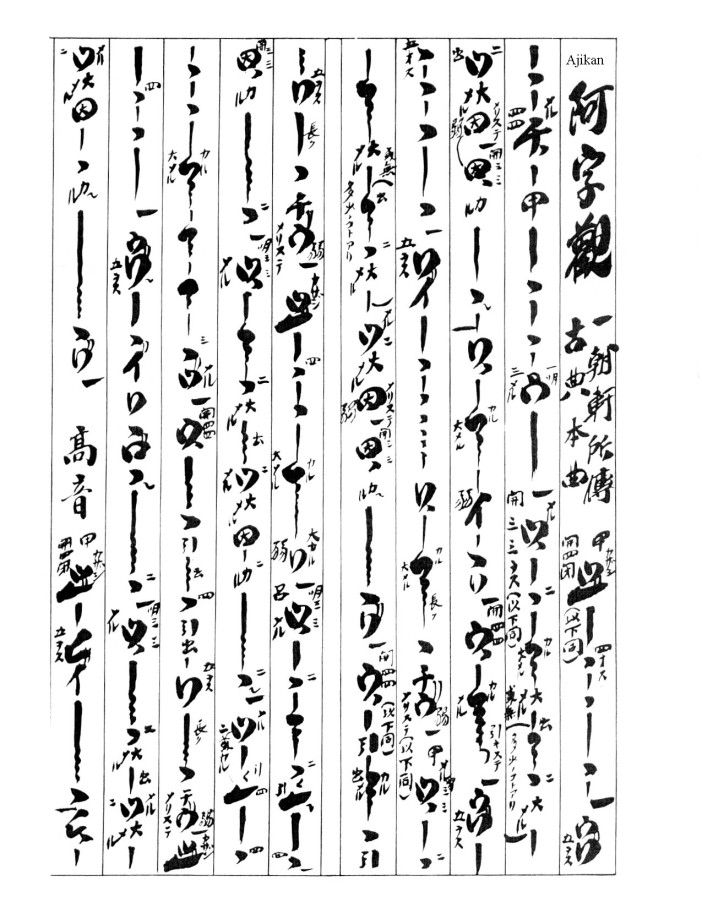

The shakuhachi is a very difficult instrument to learn. Just getting a sound can take weeks and there is an incredible amount of detail in both the playing techniques and the subtlety of the phrasing. Since the instrument has only five holes, many of the pitches and sounds we learn, in order to play the traditional music, require a combination of partial hole covering and adjusting of the head position. Then there is also the interpretation of the notation.

The shakuhachi was originally played by Buddhist monks who practiced Sui-Zen, or breathing meditation. By focusing their breathing, their minds and their bodies, in order to create sound, they engaged in mindfulness, a state of awareness. The concept of “Enlightenment in a Single Sound” (Ichi on, Jobutsu) is associated with shakuhachi practice. To practice shakuhachi is to become mindful and aware while you are in that moment.

I teach the traditional music of shakuhachi as passed down from a centuries-old lineage and strive to be faithful to the original intent of the practice. My dojo is located in Park Slope, and I also teach a shakuhachi class at Columbia University.

You received the Dai-Shi-Han (Grand Master) certificate. Tell us about the what it takes to achieve this status?

My first certificate, Jun-Shin-Han, was bestowed after more than 10 years of study, indicating that I had achieved a deep enough understanding of the music and the ability to teach the traditional repertoire. More than 100 pieces of music must be mastered in this curriculum.

The Shi-Han (Master) certificate came three years later and the Dai-Shi-Han (Grand Master) another three years later. Both later degrees are awarded based on a candidate’s achievements in promoting, sustaining and advancing the tradition. This can be achieved by being an active shakuhachi teacher (sensei) and performer. It takes a lifetime to learn the shakuhachi, so the sooner you start, the longer it takes.

Are there intersections between traditional Japanese music and music genres and styles within Western culture?

The sound of shakuhachi has been heard by many people in movie and TV soundtracks, but most often merely as sound effect. Traditional Japanese music can be quite different than Western music; different scales, rhythm, timbres, etc. However as the contemporary music world continues to seek new sounds and musical thought, so have the two traditions been coming together. I am artistic director of Kyo-Shin-An Arts, a not-for-profit arts organization that commissions and presents new works for Japanese instruments and Western classical instruments. I am also a composer of such music and have written numerous pieces for shakuhachi with orchestra and chamber ensembles.

Since you’re a neighbor, can you tell us a bit about your local haunts and favorite activities to do in the Slope?

I am a Brooklyn native (grew up in Brooklyn Heights) and have lived in the Slope for more than 25 years and raised three children here. Brooklyn is a much more dynamic place today than it was in the 1960s. And certainly Park Slope is one of the most beautiful neighborhoods. I love all the gardens in front of the brownstones, and I am an avid Prospect Park user as a runner, bicyclist, and picnicker. I also enjoy our fabulous restaurants. If I tell you my favorite haunts, I’m afraid they may become popular and I will no longer be able to get a table.

The Performance Rundown: Between Sound and Silence, a concert of Zen Buddhist Music for the Shakuhachi, Japanese Bamboo Flute

Where: Brooklyn Zen Center (505 Carroll Street between 3rd and 4th Avenues)

When: Saturday, September 26 at 7:30pm

Admission: $15 suggested donation; reservations recommended