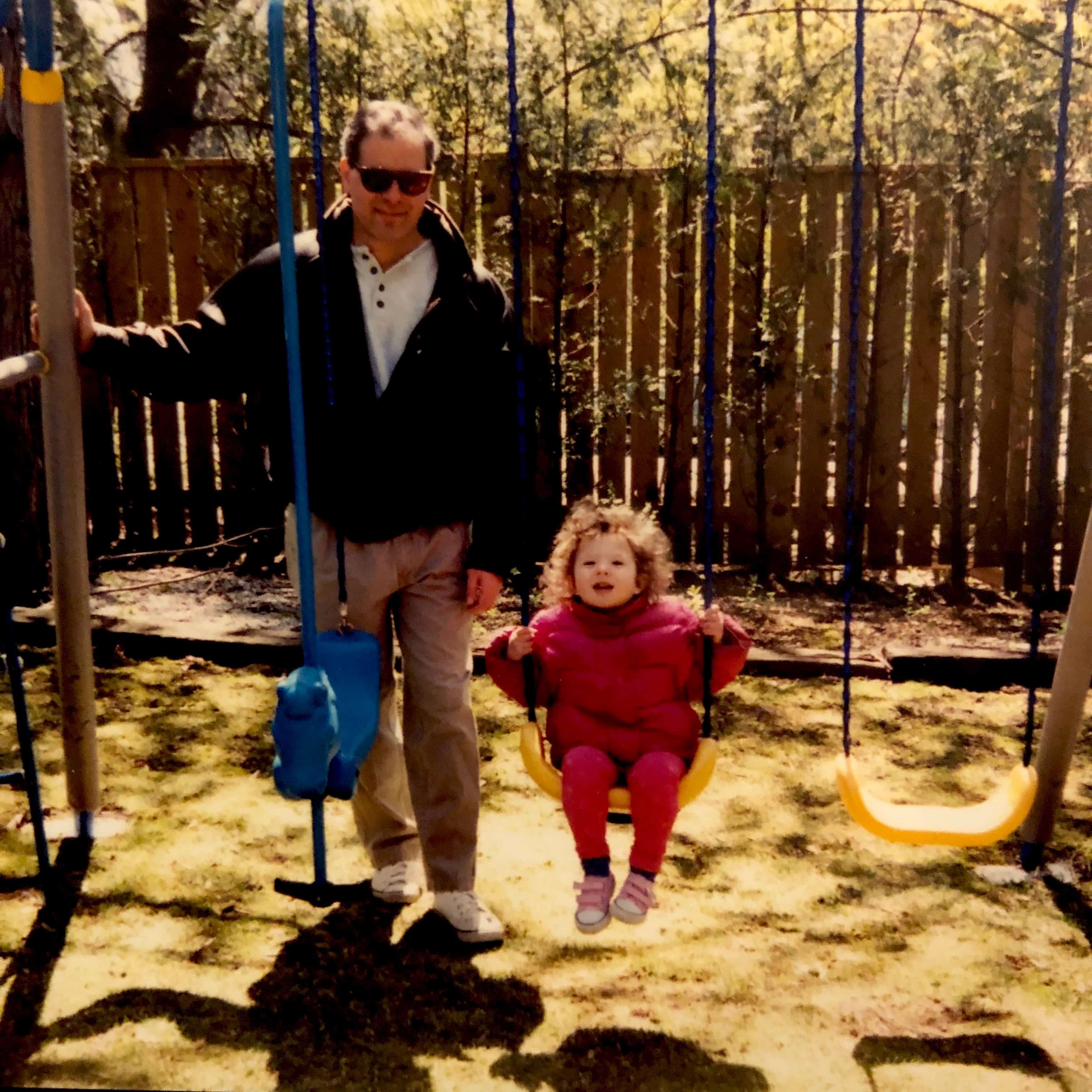

Father’s Day

Hallmark enforces the calendar’s arbitrary days of celebration. For many adoring children, this Sunday is Father’s Day. Those like me will be reminded that their father died.

COVID-19 has stopped Father’s Day celebrations all over the world.

Mask-clad daily, I’m suffocating my thoughts of self-pity. It is a privilege to wear a mask and to breathe underneath the cloth. What else am I hiding from friends and family beyond hidden smiles and obstructed frowns? My father passed away at a hospice near Kensington Market, in Toronto, Ontario – I cover my grief and cower at its power over me, years later.

Recently, a friend called me from the hospital to tell me her dad was dying: There’s fluid in his lungs, she said. I heard her voice crack in my phone. She’s blinking back tears. He’s dying. He’s been strong, but not stronger than the disease.

I close my eyes as I listen, inhale through my nose, and I can almost smell the hospital fumes: disinfectant soaps, hand sanitizers, the rubber of the gloves. The beeping of machines, the murmur of nurses, the squeak of their shoes, and the monotonous timbre of a doctor relaying news. I picture my friend, but then – I see myself, years ago in the hospital with my father. I was sixteen.

There is no correct way to mourn. Here I am, eight years later, in Brooklyn, still mourning.

In an age where we mourn on Facebook, vlog trauma, and TikTok the walk to closure, a forlorn Instagram post gets more likes than a picture of a newborn baby. People stare at others in situations of despair, in grief. It took trial, error, performativity, and creativity for my coping process to start. My art nudes pop-off when not removed by the powers that be. The key to validation is vulnerability on platforms. I feel seen.

However, now is not my time to be seen, for there are more fathers dying, human rights issues to be reconciled, systemic racism to be eradicated — more learning must be had. More mourning.

My eyes are closed as I listen to my friend on the phone. If I open them, I’m forced to confront that I am no longer in a hospital room. That my dad is dead.

I go to the funeral. I wear the dress I wore to my dad’s funeral. No one knows that. I place myself there to show care. I cannot wait to hold my friend close. I want to appeal to the adolescent, incessant, and unwavering pit in my stomach. I know this pit is in her stomach too.

I watch the casket go into the ground. My throat tightens, and my eyes well up. A lady to my left seems too close and wears perfume with notes of vanilla and peppermint. I take this as a hint – the scent, the tight clasp of her hands – that she too, maybe, is in the club, our mourning band. To my right, a man has furrowed his brow. He smells of musk and sweat in this June weather somehow. Perhaps he is a father, I quietly think. I inch toward him, turn to face him, and muster a vacant blink.

After the burial, the condolences, and the respects, I sit on the bus home and reflect. I ashamedly admit to myself that I wish I was the griever. I want the excuse to take a week off of work. I want time to heave, to cry and ask God: Why? Why today – 8 years later – does it feel the same?

Yet another friend’s dad died last week.

I went to the funeral. He was buried in a fine suit, patent leather shoes, and a new tie. The service was held on Zoom. My dad was Jewish and was buried in a smock. We mourned.

This virus has stopped celebrations of Father’s Day all over the world.

Today, I hug no one. I grieve for my father and try to breathe under the mask I wear every day … a mask that has nothing to do with the pandemic.