Community Plans For Bushwick, Worries It Will Not Matter

BUSHWICK – From 2008 to 2018, the median price of a Bushwick home jumped 84 percent, making rent more and more unaffordable for those who have been there longest. High-rise, luxury apartments, co-working spaces, and artisan coffee shops line streets which used to be mainly occupied by single-family homes.

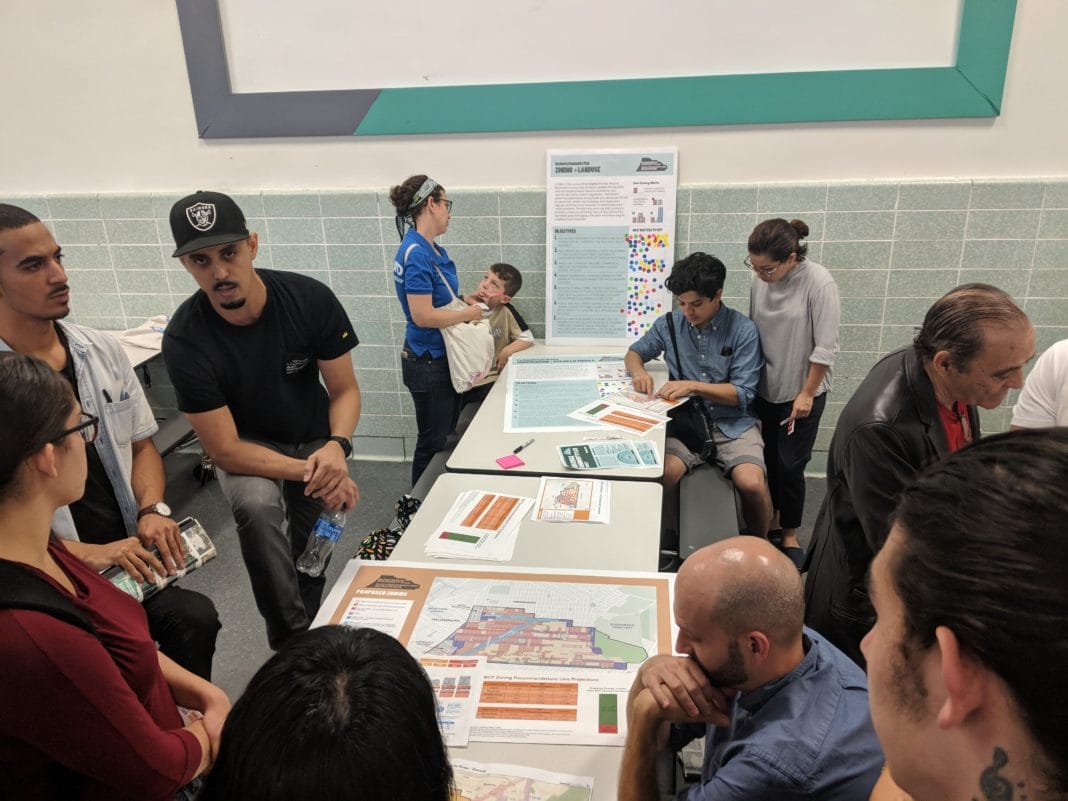

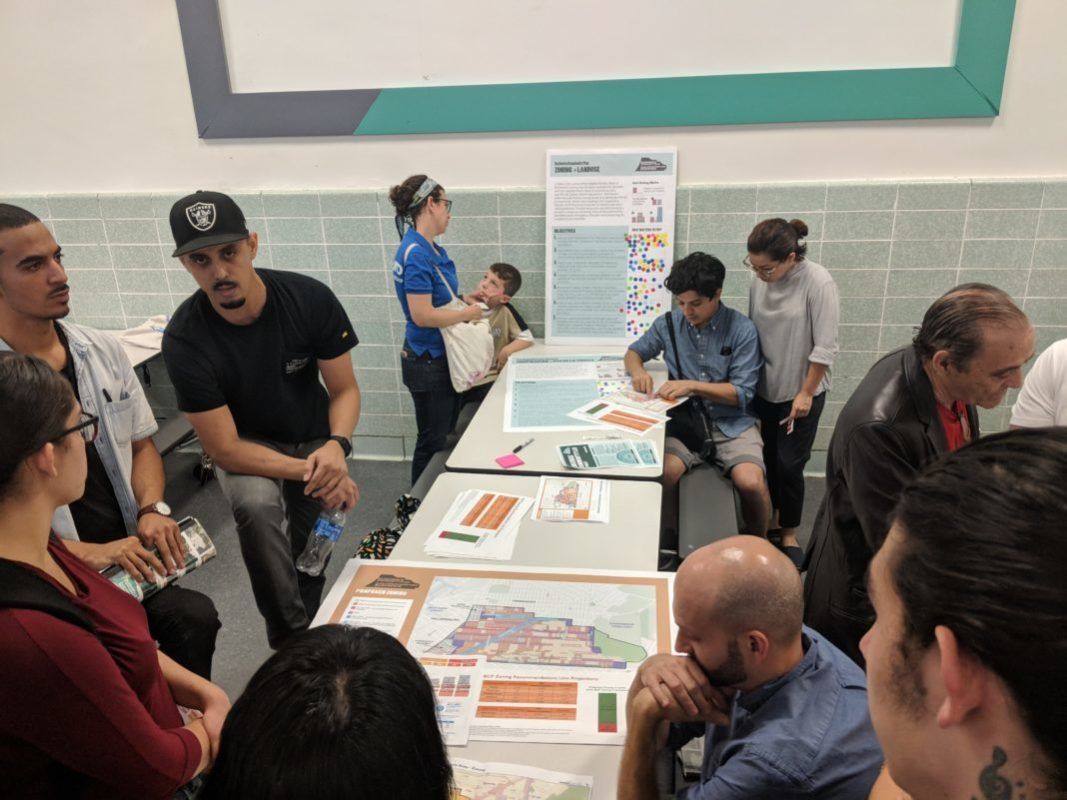

The continued gentrification and displacement of tenants who can no longer afford their rent led residents, nonprofits and local politicians to come together and create the Bushwick Community Plan (BCP), a rezoning guide outlining how Bushwick residents would like to see their neighborhood grow.

The plan, which was submitted in September, calls for a slew of changes including down-zoning housing, declaring some areas historic districts and investing in open space and health resources. However, this guide, which took dozens of people and four years to create, doesn’t actually have to be used. The government has no obligation to implement anything in the proposal, a fact which has fueled uneasiness among its creators and animosity from those who oppose the plan altogether.

Bushwick District Manager Celestina Leon says that the Department of City Planning’s (DCP) rezoning plan will most likely differ greatly from the one the community board presented, specifically regarding Bushwick Community Plan’s requirement that manufacturing space not be converted to residential space.

“We don’t want to lose the space that provided jobs for people for years,” Leon says. “Once you get rid of manufacturing, it’s most likely never going to come back. Once it’s rezoned the development happens so quickly—hotels, bars, commercial establishments—things not providing the same kinds of jobs [as manufacturing].”

Leon says that city officials claim to have heard Bushwick residents, but their behavior thus far says otherwise. According to the Village Voice, Winston Von Engel, director of DCP’s Brooklyn office, implied at a meeting that the city was interested in keeping the architectural integrity of the area, but not bringing back any jobs or ensuring that the building could only be used for manufacturing.

“This isn’t a good deal and this isn’t going in a good direction,” local business owner Edwin Delgado told The Village Voice. “And the more time they take, the more families are being displaced.”

Community board member Robert Camacho has lived in Bushwick for 58 years and shares Leon’s concerns about manufacturing. Growing up in Bushwick, he says there used to be stricter rules about land use, but today factories are being turned into lofts and dance clubs, both of which have him asking “how the hell is that even possible?”

“When I was a kid my dad rented his basement because he worked in a factory, and somebody called the city on my dad and he had to pay a fine and break the basement up and stuff,” he says. “Now, people are doing a lot of stuff illegally.”

Some are cautious about the plan itself, and wouldn’t be thrilled to see the factories reemerge. Owner of Tina’s Place Athina Skermo says when she first opened the diner in 1969 her customer base was workers from the Boar’s Head meat plant and other neighboring factories.

Her kids and grandkids would come help after school, and she remembers thinking it wasn’t good for them to see some of the characters who came in and out. “It used to be very bad,” she says. “Lots of break-ins. Lots of fights. Prostitutes and people would overdose in the bathroom.”

Her son Raymond Skermo says him and his mom haven’t seen the plan, but if it negatively affects how many people are moving in, they won’t like it.

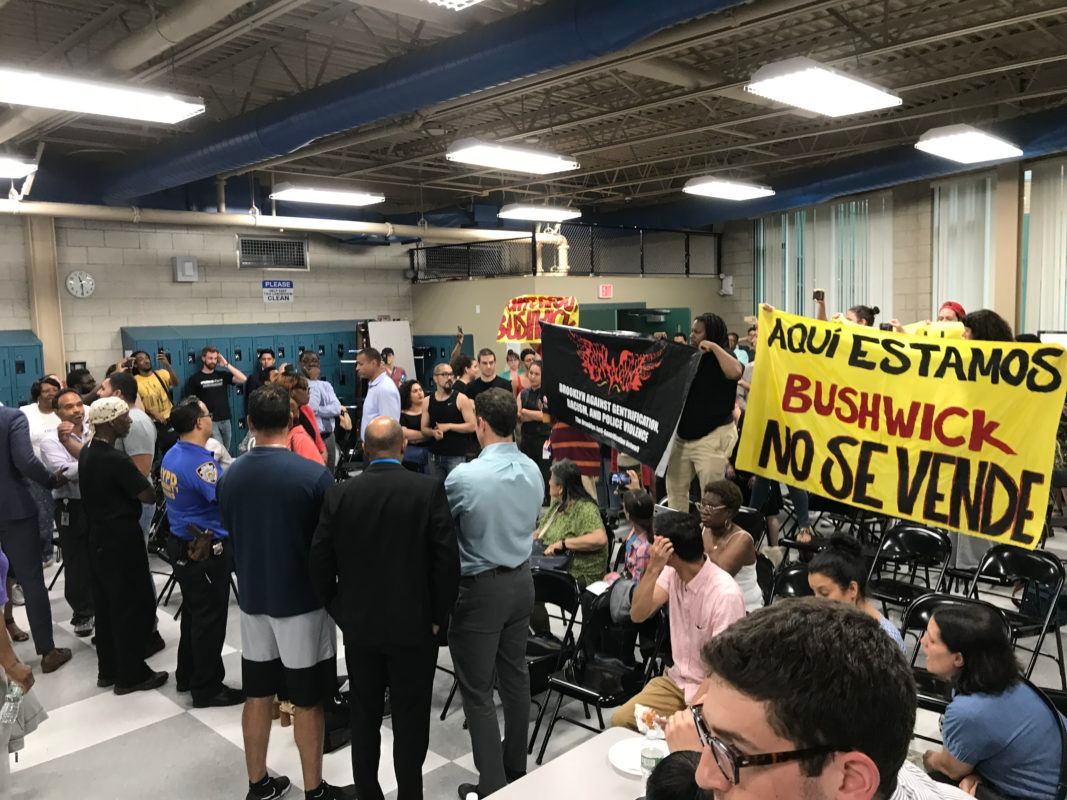

Others, like anti-gentrification groups Mi Casa No Es Su Casa, The Audre Lorde Project and G-REBELS, are against the plan altogether, calling it a sham. Bushwick was not scheduled to be rezoned by Mayor de Blasio, and they feel like the Bushwick Community Plan unnecessarily opened the community up to a rezoning that will end in more displacement.

And Leon says, they have a point. Historically, the city doesn’t adequately take heed of community plans. In Crown Heights, city council approved a community plan which rezoned 55 blocks of Crown Heights West in order to preserve the neighborhood’s character but didn’t include any requirement for affordable housing, which the original community plan called for. And in Manhattan, the Chinatown Working Group spent five years drafting a plan that would help preserve the affordability of the neighborhood by creating a “Special District” that would implement protections for immigrants, working class and public housing residents. It would also ban “supertall” structures. In 2015, the DCP dismissed the plan for being impractical.

Leon says that East Harlem is another good example of a revised rezoning plan put forth by the city which garnered mixed reviews, with many concerned that affordable housing won’t be available for those making under $10,000 a year. Opponents also questioned some of the investments the rezoning includes, such as $25 million for East Harlem’s public market, La Marqueta. Marina Ortiz, an advocate with East Harlem Preservation and a board member of the East Harlem-El Barrio Community Land Trust told City Limits that these investments are “‘looking toward the future,’—and that future will not include us.”

The rezoning plan in Industry City, which proposes 1.3 million square feet of new commercial and industrial space, has led Sunset Park residents to worry about further gentrification to their neighborhood, and looking at an independent study to asses impact of proposed changes.

Leon says this information paired with what the DCP has communicated with Bushwick residents so far doesn’t instill much trust. “The question is, how much confidence do we have in our council members being able to push this forward,” she says.

Council member Antonio Reynoso also wants this plan to be history-making, in that it’s a plan the community actually supports. “I want to make sure that this is the first plan that gets pushed through, word for word. I want this to be the first rezoning plan that the community supports, not that the community fights,” he said when the plan was presented, according to The Bushwick Daily.

Chief Executive Officer of Riseboro and contributor to the Bushwick Community Plan Scott Short believes that the word “rezoning” garners a knee-jerk pushback, but that inaction would have been worse. “Bushwick is going to continue to grow,” he says. “And we put forth a plan to make sure the development evolves to make [the community] an inclusive and equitable place.”

Leon says that the board should hear from the city by mid-April how much of the Bushwick Community Plan will be implemented.