Brooklyn’s Accidental New Town Square

When the Barclays Center was designated one of “The New Shapes of New York” by the New York Times in 2016, Justin Garrett Moore, executive director of the city’s Public Design Commission, saluted the “pedestrian-oriented public spaces.”

I scoffed, since the privately-controlled plaza was not just sponsored by Resorts World Casino NYC, its presence was an accident.

Since May 29, though, crowds protesting police brutality and racist killings—triggered by the gruesome killing in Minneapolis of George Floyd—have converged at Flatbush and Atlantic avenues, turning that plaza into Brooklyn’s new Town Square. The Barclays Center, thanks to its location at Brooklyn’s largest transit hub, its proximity to residential neighborhoods, and its mothballed-by-pandemic status, has become the locus of activism in Brooklyn.

Nightly crowds of chanting, sign-wielding protesters calling for justice have faced off against police, separated by metal barricades. The protests have been mostly, though not entirely peaceful, with moments of silence (and empty chairs for the mayor and governor), prayer, and taking a knee, quickly shifting to angry clashes with cops, pepper spray and worse.

The Barclays Center Responds

For days, the digital signage in the oculus, the arena’s oval canopy, projected discordant ads from GEICO, Ticketmaster, and JetBlue. On June 7, ads ceased at what one observer dubbed “Standoff Center.” The oculus offered a quote from Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr.—“The time is always right to do what is right.”–more gnomic than “Black lives matter.”

That same day, Taiwanese-Canadian billionaire Joe Tsai—the Alibaba co-founder who in 2017 bought a piece of the Brooklyn Nets from Russian oligarch Mikhail Prokhorov and in 2019 bought the rest, as well as the arena operating company—offered a calibrated statement to the New York Daily News.

“We have said that we will use the voice and platform of the Nets, Liberty and Barclays Center to facilitate empathy and dialogue,” Tsai said. “In Brooklyn, the Plaza”—he omitted the official name—“at Flatbush and Atlantic has become a place for people to assemble and have their voice heard. If it continues to serve as a place where everyone from our community—from residents to businesses to police alike—gather peacefully to listen to each other and find common ground, then it’s good with me.”

The plaza is hardly Brooklyn’s Hyde Park Speakers’ Corner, at least not yet. Cops were seen as not just policing protests but also defending the arena, and graffiti left by the protesters tagging signage (before, after) and Ona, the sculpture in the plaza, has consistently been cleaned up. The pavement chalk slogans like “Black Lives Matter” and “Dissent Is Patriotic” are reappearing daily.

On its back cover, the Daily News generously hyped its mini-scoop as “Nets owner happy to see team’s home become Brooklyn’s home for non-violent protest.”

Still, it’s hard to imagine that J Tsai Sports, until recently more focused on growing NBA fandom in China, where Alibaba prospers, sought that role. Arena managers had to improvise, reframing a privately controlled space as a public asset and suspending the plaza’s many rules rendered unenforceable by crisis.

Still, this and another Nets/Barclays statement decrying racial discrimination, plus Tsai’s significant donations to fight the coronavirus pandemic, represent a savvier strategy than that of the too-long silent New York Knicks/Rangers and the tone-deaf New York Islanders.

A De Facto Town Square Emerges

The past ten days have changed the perception of the arena.

“My wife remarked the other day that for barclays center the protests have done in 1 week what the last decade hasn’t made it feel like part of the community. de facto town square, center of spectacle etc.,” tweeted New York Times reporter Andy Newman.”

“Some guy just stopped to tell me he felt bad for Barclays Center having to be a magnet for protests,” NY1’s Roger Clark tweeted. “Weird to hear that after covering years of protest against construction here.”

“I felt it was sort of a righting of things,” came one response. “I don’t know who thought initially to use Barclay Center as a hub but it was brilliant.”

Some expressed pride. “Barclays Center is, in many ways, a public good though it makes money for private enterprise,” one NetsDaily commenter observed. “A public space, with national branding and awareness, became the space for a public protest.”

That, of course, was never the plan, especially since the much-hyped arena project wasn’t supposed to have a plaza and some never wanted an arena there.

“Jobs, Housing, and Hoops”— Plus An Atrium

In December 2003, the announcement of an arena project in Brooklyn, then dubbed Atlantic Yards, triggered enormous pushback, given the plan to wedge an 8-million square-foot project with 16 towers into Prospect Heights at the edge of Downtown Brooklyn.

The neighborhood was gentrifying, at a far lower density, yet also awaiting development. City and state officials had not marketed development rights for an 8-acre railyard, which would require an expensive deck. Nor did they see value in other underutilized public property, like the city-owned lot used as an MTA storage yard, guarded with barbed wire, at the tip of Atlantic and Flatbush avenues, where the former Ebbets Field flagpole stands today.

To those resisting Atlantic Yards, it represented overdevelopment, an abuse of eminent domain and sweetheart deals for powerful local developer Forest City Ratner, with a state public approval process that bypassed local elected officials.

To those welcoming it, it represented what Forest City called “Jobs, Housing, and Hoops”: a return of major league sports to Brooklyn and a venue worthy of a city-like borough, plus construction jobs, office jobs, and “affordable housing” that might counteract gentrification. Many of the promises made by developers haven’t been met.

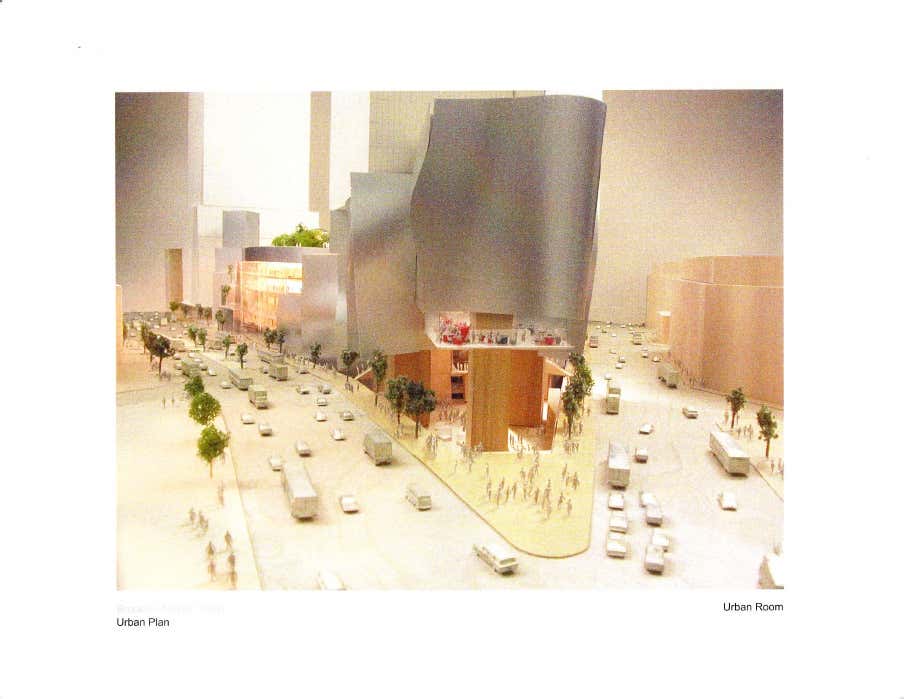

A key Atlantic Yards selling point was Frank Gehry, the world’s most famous architect, who was to design the entire project. His arena would be surrounded by four towers, notably a wedge-shaped showcase at Atlantic and Flatbush, Brooklyn’s tallest building, which Gehry dubbed “Miss Brooklyn.”

“The design’s most exceptional feature is the configuration of office towers surrounding the arena,” New York Times architecture critic Herbert Muschamp rhapsodized after the announcement. He cheered the planned public space on the arena’s roof, as well as the street-level “‘urban room,’ a soaring Piranesian space” at Atlantic and Flatbush serving the arena, “Miss Brooklyn,” and the Atlantic Terminal transit hub.

Muschamp’s successor Nicolai Ouroussoff also hailed Gehry’s atrium, a “vast public room.” By embedding an arena “in layers upon layers of housing,” Gehry had managed to “bury” a tired formula for standalone venues, he wrote. (Three towers had been reassigned for apartments, not office space.)

Revising The Arena During 2008 Recession

However, as Forest City executive Jim Stuckey once warned laconically, “Projects change, markets change.” In 2007, Forest City snagged Barclays Capital, a British bank eager to make a big splash in the United States, as arena naming rights sponsor, in part thanks to Gehry’s role. But the starchitect didn’t last.

During the recession of 2008, developer Bruce Ratner dumped Gehry’s design for a smaller, cheaper arena, decoupled from the towers, which would be built piecemeal.

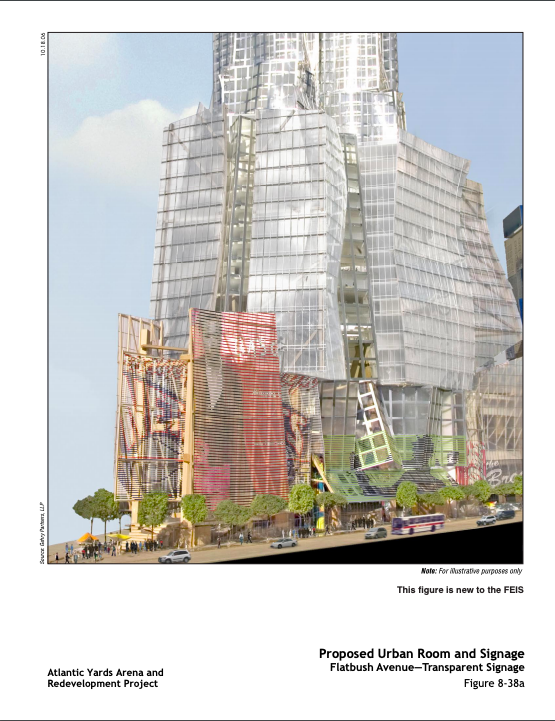

The functional but prosaic design, based on the Conseco Fieldhouse in Indianapolis, came from the firm Ellerbe Becket. Once a leaked image was derided by Ouroussoff as a “charmless monstrosity,” Ratner smartly hired the buzzy firm SHoP to wrap Ellerbe Becket’s structure anew.

SHoP devised the Barclays Center’s signature pre-rusted metal sheath, plus a distinctive oval canopy, the oculus, to deliver digital ads and signage. With no market for “Miss Brooklyn,” SHoP instead produced a plaza.

That plaza, announced as temporary, now seems permanent, given the key role it’s played serving arena operations. Indeed, since 2015, project developers have sought to shift the bulk of the unbuilt “Miss Brooklyn” across Flatbush Avenue. (In 2014, Atlantic Yards was renamed Pacific Park, once Shanghai government-owned Greenland USA became majority owner.)

Across from the arena, instead of the large tower previously approved to replace the big-box stores Modell’s and P.C. Richard, Greenland has proposed a giant two-tower project. One justification: it would preserve the plaza. (The bulk shift requires state approval, and seems stalled for now. Here’s a look at Pacific Park’s current state and future plans.)

Plaza Promises, Plaza Realities

In 2010, upon unveiling the plaza design, developer Ratner claimed it would “quickly become one of Brooklyn’s great public spaces.” Beyond serving the arena, he said, “it was also designed much like a park so it can be programmed for community events and diverse activities, such as a greenmarket and holiday fairs.”

At a public meeting, SHoP partner Gregg Pasquarelli said, “Forest City Ratner is very interested in working with the community” regarding plaza programming. Café tables might be set up. “Wouldn’t it be great,” he added, “to have to have a live digital feed of Prospect Park on the inside of the oculus?”

Well, that plaza’s never been a park, and no one’s viewed Prospect Park on the digital feed to our knowledge. Yes, there were sporadic farmers’ markets and food truck rallies in 2013, poorly attended concerts last year, and, more recently, a food pantry with the Food Bank of New York City.

But the plaza has more often served to distribute t-shirts, make videos, hold a boxing weigh-in, host a live band for hockey fans, welcome an early morning TV shoot, or create a mural, activities often tethered to sponsors. In 2014, elected officials held a pep rally there, aiming to attract the 2016 Democratic National Convention.

After all, despite below-market or free land, tax breaks, and $100 million of taxpayer money to acquire private property to develop the arena and plaza, it’s not truly a public space. The arena and plaza, though nominally owned by New York State to enable cheap tax-exempt financing, are controlled by Tsai’s private entity.

Posted rules for the privately operated space prohibit amplified sound, destroying or marking any property, posting advertisements, and street performances—rules that are very much enforced during more peaceful times, such as ejecting my Jane’s Walk tour last year concerning Atlantic Yards/Pacific Park. (They are not as diligent about policing their own operations – the arena itself has regularly encroached on public space, using sidewalks near the loading dock on Dean Street for deliveries and illegal parking.)

A Space For The Public?

Despite the rules, the plaza has tolerated dissent before. Develop Don’t Destroy Brooklyn and allies organized a protest on Sept. 28, 2012, ahead of the arena opening with a Jay-Z concert.

On Dec. 8, 2014, crowds protesting Eric Garner’s death at the hands of the NYPD–gasping “I can’t breathe” after a chokehold– held a “die-in” at the arena plaza. One activist’s sign–“Respect existence or expect resistance”–today seems powerfully prescient.

What next? At some point, even if the arena can’t hold large events, it will shift back to commercial activities–say, for example, welcoming Brooklyn Nets fans to the plaza when the NBA season resumes in Orlando, scheduled for July 31.

Will that MLK quote stay in rotation, even after the ads return? Will the Barclays Center welcome more dissent?

The arena will always have a complicated role as a symbol of gentrification or renaissance in Brooklyn, depending on whom you ask. For now, the plaza, however accidentally, has fulfilled a 2010 prediction from architect Pasquarelli: “it’s quite a significant space, it’s something that’s very civic.”