100 Most Jewish Foods – A Conversation With Tablet’s Alana Newhouse

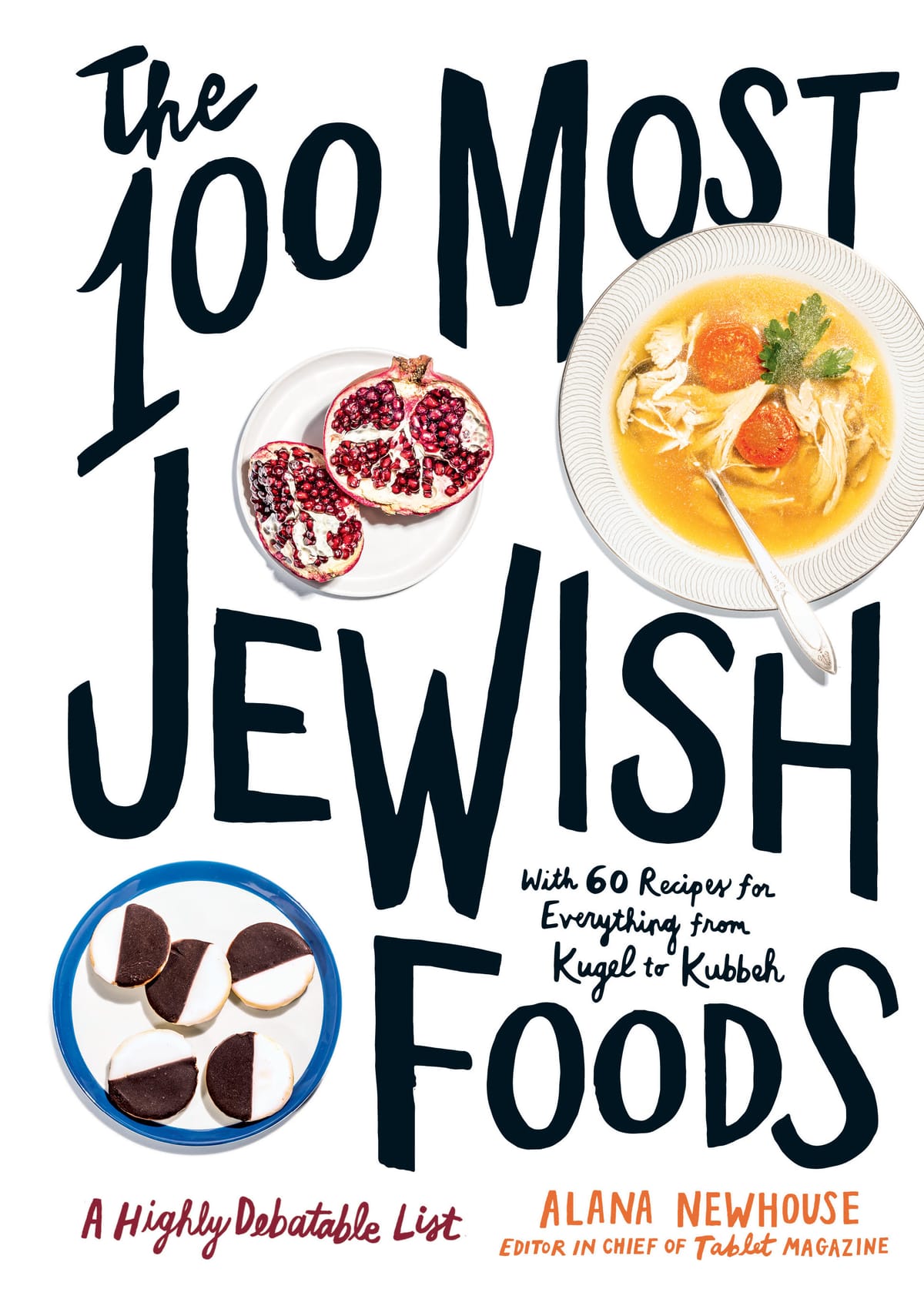

BROOKLYN – The 100 Most Jewish Foods, a book by Tablet’s editor in chief Alana Newhouse, is a perfect gift for this Passover — gorgeous and funny and well written. It is, if you like food and/or the Jewish tradition, a delight. Naturally heavy on Brooklyn, The 100 Most Jewish Foods is also unafraid of the ways in which food can be a window into history, culture, and politics. We’d expect nothing less from folks behind Tablet – the leading online magazine about Jewish identity and culture.

I had the pleasure of talking to Newhouse, who lives in Brooklyn Heights, about all those things last week. The following conversation is slightly edited and condensed for clarity.

LZ: The book weaves together food, recipes, history, and experiences – how did you settle on the concept?

AN: I feel like the conversations about identity and culture that have been happening in the country, so many of them important and long overdue, given the vagaries of the internet quickly turn very toxic and not at all deepening, which is not what you want those conversations to do.

One of the things that struck me was that food was one of these places where people and particularly Jews, but I’d say that probably holds true for all cultures, where they could talk and feel about their history and identity – bravely. They did not have to apologize for not knowing enough, or not being left-wing enough or right-wing enough – they were just able to engage with no constraints. And so I thought – well – if that feels good to people, feels safe to people- let’s use that to have that deeper conversation, particularly about Jewish history and the global community and how we understand that.

LZ: Tell me about the process. What was it like deciding who gets matzo and who writes about chopped liver, choosing what to include? The list is alphabetical and includes gems like Chinese food, sushi, and used tea bags, among more traditional challah, kugel, and shakshuka.

AN: At Tablet we had done a number of lists, like the 101 great Jewish books, films, and such, so we knew we had to blow the doors open, both in terms of what’s going to be on the list and who was going do it. We were lucky to work with Gabriella Gershenson, an unbelievably brilliant food editor, who helped us cast out a wide net, and then we paired it down.

As we paired it down, and it took a few months, we realized that say kishke, derma and helzl are inherently the same – meat stuffed in different things depending on the region one came from, though helzl uses chicken’s neck as a casing – so we consolidated the entry.

One thing that bugs me is that – and I am going to put myself out there – challa really should not be on the list. Jews are supposed to have bread on Sabbath, but people in each region developed their own. Challa is a sabbath bread, and I think it should be with what ended up as the Yemeni bread entry, not standing on its own, but it is a fight I lost. Challa has become too iconic for the contemporary Jewish community. The list was supposed to be both familiar and challenging, and I was told I was becoming too esoteric about it.

LZ: You published the list on which the book is based in the spring of 2018. What was the feedback you received?

AN: Well, within hours there were Tweets saying it was a “super Ashkenazi,” “super New York” list. They saw a picture of chicken soup and lox and had a knee jerk reaction. In fact, there are dishes from global communities from around the world, often written by people from those communities. That was the one reaction that annoyed me after the list as published. Otherwise, the feedback was excellent. A lot of teenagers really like it, really somehow find it exciting.

LZ: Do you think it is because it is accessible?

AN: The contributors are not all Jewish. The entries engage with how Jews live in the world and have lived in the broader society. It doesn’t feel, I hope it doesn’t feel insular. And I think that a lot of people have reacted to that. It feels like you are engaging with something that is at once authentic and specific while not feeling like we are closed off.

LZ: Like the borsch entry?

AN: Or like Marcus Samuelson’s entry on lox which is amazing and is in some sense about the bigness of these foods and how broad their reach is, both practical and emotional. And then there is the Amanda Hesser and Merrill Stubbs brisket entry, which is amazing. They just got it right away – “We have, we absolutely have a perspective.” I think that people like that they can feel like they can engage with their Jewishness without getting lost in something that feels too constricting. The story of Jewish food is a story of particularity but also a story of worldliness.

LZ: A practical question – where do I get all this food?

AN: First of all, you have to ask yourself if you care if it’s kosher. But I would like to say that even if you don’t care, kosher stores are a perfect place to start because there is a good chance they will have what you want. If you took our list to the Pomegranate in Midwood or to Russ and Daughters you could get upwards of 20 of the things on the list. At Pomegranate more than that. But then there are also things you cannot. For example, eyerlekh, which are unhatched chicken eggs, I think the only place in the city you can get them is in Chinatown.

Then there’s stuff like Jacobs lentil stew – its a dish from the bible. It is not something Jews make – its a conceptual entry. So, I don’t know how you’d source that. I’m at heart a newspaper reporter, so I just want people to get out and go, go to Lee Avenue and peek your head into these stores and see what they are selling. That’s what I would encourage people to do.

LZ: Your list of contributors is heavy on Brooklyn residents, past and present. How do you think of Brooklyn and its role in Jewish life?

AN: When a place becomes an icon, it is hard for the place to remain a real place, and Brooklyn is both of those things. Its both historically incredibly significant, culturally iconic and just a place where you still live, which makes it somewhat unusual. A lot of times things become iconic once they are over, which is not the case for Brooklyn.

LZ: Brooklyn is quite diverse among its Jewish communities.

AN: Different Jewish communities maintain different threads of the Jewish culinary history in the borough. More secular Jewish communities maintain the more popular cultural Jewish traditions. I think it’s not insignificant that Russ and Daughters just opened in Brooklyn. It is important, and it means something about the resilience of this food as part of the borough’s identity.

Brooklyn maintains its role as the native place for many different kinds of Jewish communities including communities that aren’t comprehensively Jewish [meaning they include non-Jews]. You have access to and engagement with Jewish culinary life whether you are aware of it or not and just because you are not orthodox and keeping kosher and going to the same six stores, it does not mean you are not holding up a thread of something. The fact that Brooklyn is able to maintain all of those different threads from many different kinds of jews, means it is sustaining a certain kind of iconic status that makes it very important.

LZ: Increasingly covering Brooklyn for us has also meant covering antisemitic incidents in Brooklyn, and it has made me think a lot about how people talk about each other and how we engage with each other. How do we get neighbors to acknowledge each other and our right to peacefully coexist?

AN: I think we should not pretend there are no differences among us. After 9/11 I covered religion and went to so many Muslims-Christians-and-Jews-get-together events, and after a few of them – it struck me how limited they were in their power because they were speaking to the converted. We need to talk to the people who are the most inside of their communities, communities, the most representative of the individual community’s fears, concerns, and impulses.

LZ: Those are not pretty pictures.

AN: But you have to go to the not pretty pictures. Otherwise, you are not going to move the needle. It’s like you go to couples therapy and all you do it hear – let’s just talk about what you love about each other. Oh, forget it, its never gonna work. You have to actually address the things that are causing the conflict and be unafraid. I also think the internet is a terrible platform for this. It is very hard to be hateful to someone to their face, or at least much harder than over pixels.

The conversation about antisemitism is very complicated. Brooklyn’s experience is very specific, and to do with specific communities that have a long history together. We make a mistake when we try to erase the specificity of Brooklyn and try to imagine national or global trends as being perfectly applicable in every specific instance. Not to say they are irrelevant. They are not, but this is a very specific place, with a very long and very specific history, and very specific politics, very specific geography and all of this plays into real life human beings on streets having specific interactions. I think Brooklyn really does deserve to have this addressed in its specificity.

LZ: Why do you think it is so hard to talk about it, have meaningful engagement?

AN: There is an incredibly radioactive conversation happening on the national level. Nobody in Brooklyn wants to be part of that. The fear is – we have these conversations, and we are made into pawns with our neighbors on national TV talking about global antisemitism when all I want to talk about is antisemitism on Nostrand Avenue. Which is totally different. I understand why people are hesitant. They don’t want to be pawns in someone else’s media game. I just want to fix my school, my street, I do not want to be on FOX, and people no longer know how to address things now. Traditionally the way to address this was locally. I don’t think it can happen anywhere but literally on those streets.

LZ: Think food can help?

AN: I hope so. If it can help, I will bring it myself.

In the meantime – read the book, available at local bookstores and online.