With Schools Closing, Is Catholic Education Disappearing in Brooklyn?

This week marked the last day of school for the Diocese of Brooklyn’s Catholic schools, with summer break now underway. But for some of those long-standing schools, their doors will not reopen in September.

Earlier this year, the Diocese announced the closing of two K-8 schools – Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Academy in Bensonhurst, and Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Academy in Mill Basin – along with the merging of two Bushwick schools, St Brigid and St. Frances Cabrini. Recently, the famed all-girl’s high school, Bishop Kearney in Bensonhurst, announced its abrupt closing, while St. Joseph High School in Downtown Brooklyn announced it will close in June 2020.

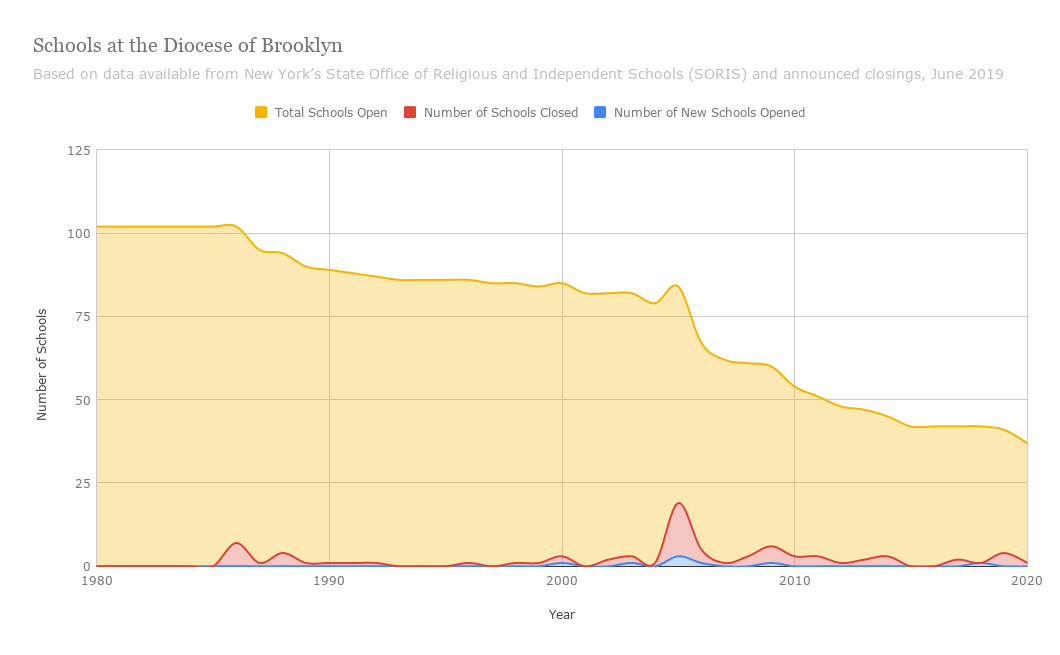

All these closings – including the high schools, which are run by the Sisters of St. Joseph and are not part of the Diocese – are being added to the long list of Brooklyn Catholic schools that have closed since the mid-2000s. According to New York’s State Office of Religious and Independent Schools (SORIS) about 45 schools have been closed by the Diocese of Brooklyn since the mid-2000s, and as of now there are only 36 left that have not been scheduled to close, a fraction of 102 schools that welcomed students back in 1980s.

“This is a very challenging time for schools and educators,” says Ted Havelka, the Diocese’s Enrollment Manager. “The schools are not able to maintain the same numbers.”

One of the biggest factors in closing a school is because of its declining number of students. According to The Tablet, Queen of Heaven saw a decrease of 60 percent over the period of five years. Our Lady of Guadalupe saw a drop of 75 students during that same time. Even St. Brigid and St. Frances Cabrini saw declining enrollment, hence the merger.

“Brooklyn is a great place to raise a family,” says Havelka. “But there’s financial constraints. Rent and housing costs are a major challenge.”

Havelka points out that many of the families they serve are leaving the borough due its high cost of living. At one school he recently visited, he was told about five or six students would be moving at the end of the school year, to either Long Island, New Jersey or Florida.

Another reason for the closures are budgeting issues. The Tablet reported that both Queen of Heaven and Our Lady of Guadalupe have deficits in the thousands.

Education expert Joseph Viteritti, the Chairman of the Department of Urban Policy and Planning at CUNY’s Hunter College, suggests the child abuse scandals in recent years may have not only blemished the reputation of Catholic education, but factored into the financing of the schools.

“The lawsuits became a burden,” Viteritti says. “The money comes from somewhere.”

But John Quaglione, spokesman for the Diocese, says that is not the case.

“That’s not factual,” Quaglione says. “The parish and the schools are separate.”

He explains that six years ago, Bishop Nicholas DiMarzio made a declaration that the schools become academies, so they would stop receiving subsidies from the parish. Those academies are run by a Board of Members and Directors, rather than just the pastor of the parish.

Whatever the factors may be, the closing of so many Catholic schools in recent years is not only a loss for students attending those schools, but also for Brooklyn itself.

According to Viteritti, those schools were a way to build Catholic communities, particularly for immigrants from Ireland, Poland and Italy. The families attended their local Catholic church on Sundays, and their children went to those parish schools during the week.

But as the ethnic demographics changed in Brooklyn, so did the Catholic schools’ role.

“Catholic schools became a resource for African-American and Latino families,” Vitteritti explains. “The public schools were not serving them well. So the mission became less about religion, to serving a community in need.”

It should be noted that while these schools do teach the Catholic faith to its students, many of the students are not Catholic, or even Christian.

“There’s one school that has over a dozen of religions,” Havelka says. “We’re incredibly diverse. We see families who want an environment that mirrors what they want to teach at home. They like the smaller classes. There is a strong demand for a value-focused curriculum.”

For many years, Catholic education had a reputation for its discipline, academics and high college acceptance rate. But these days, it is seeing another school organization produce the same thing.

“Charter schools provide an alternative without tuition,” Viteritti says. “They are doing much better than public schools academically, and it’s more profound with African-American and Latino students.”

He points out that he predicted this would happen in his book, Choosing Equality: School Choice, the Constitution and Society. It was published in 1999, just a few years before charter schools began setting up in Brooklyn, which was around the same time when the Diocese began closing many of its schools.

“Charter schools are seen on the same level of public schools,” says John Quaglione. “It does pose a challenge to us.”

Even so, both he and Havelka point out that the schools have a variety of programs that are meant to keep up with the other systems. They include STEM labs, music and art programs, and the use of iPads and Chromebooks.

Although the Diocese admits there are challenges up ahead to keep their schools open for future generations, they are optimistic and say supporters of a Catholic education could do their bit to keep it going.

One way is through Futures in Education, the Diocese’s fundraiser for its schools. There are opportunities to be an Angel Donor to a student, or even donate or raise money for programs.

Havelka also says alumni could get involved in their school’s boards or spread the word to anyone looking for a school for their child.

“It’s still not too late to enroll,” he says. “The schools are open in the summer. Families still want a values-based education. We’re very optimistic.”

Still, it is likely that the future of Brooklyn’s Catholic schools are uncertain.

“Look at the pattern” Viteritti says. “It’s declining in numbers. At some point, they’ll hold on and then level off. But I hope they continue. It’s sad to see choices evaporate. The more choices and opportunities, the better.”

Thursday saw the final day of Our Lady of Guadalupe Catholic Academy, and Mary Queen of Heaven Catholic Academy saw theirs Wednesday.

“It was emotional, very,” says Elesa Williams, a secretary who had worked at Queen of Heaven for 11 years. “When you know these kids and parents, it’s tough.”

She takes a deep breath to hold in some tears. “We’re packing. I’m sitting here, having to send out report cards to new schools.”

“I don’t like saying good-bye,” she adds. “I told the kids, ‘see you later’.”