Three Powerful Exhibits At Brooklyn’s African Diaspora Arts Museum

Because of the distortions introduced when you try to depict a round globe on a flat sheet, most world maps show the continent of Africa as much smaller than it really is, relative to other places in the world.

The same thing can happen with Western ideas about African culture; the art, music, and literature of a diverse continent and the people who trace their roots from there can shrink to a single notion.

In a very small space at 80 Hanson Place, the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts manages to sketch a truer map, with room for a wide variety of cultural expression. Three current exhibitions, originally scheduled to end February 26 but now extended through March 12, are particularly successful in the museum’s mission to “incite dialogue on pressing social and political issues facing the African Diaspora.”

“Surrogate Skin” pairs the works of African-American artists Doreen Garner and Keisha Scarville in a provocative and poignant exhibit. Photographer Glenna Gordon’s “Diagram of the Heart” offers a glimpse into the unique Nigerian genre of literature littattafan soyayya.

“Tea Time” a series of large works on vinyl by Theresa Chromati that are visible from outside the museum in the window gallery, is at once playful and challenging.

Doreen Garner’s sculptural work in “Surrogate Skin” recalls the medical exploitation of black women’s bodies, using silicon, pearls, hair weave and surgical instruments in grotesque arrangements that suggest human organs.

Two particularly notorious stories are called out explicitly in the works. “Reliquary for Henrietta Lacks,” centered around a gleaming chromed skull, comments on the case that will be featured in an HBO film to be released in April. The skull, a small vial gripped in its teeth, rests on a red pillow and a veil of black hair.

A biopsy was taken from Lacks’ cervix when she gave birth to a daughter in 1951. Without her knowledge, cancerous cells were used as progenitors in a line named HeLa that has been used in medical research ever since, though Lacks died without ever knowing her tissue was being used.

Another piece references the sinister work of J. Marion Sims, hailed as “the father of modern gynecology.” The 19th-century physician purchased slaves to use as the subjects of his medical research. Three of them named in his records, Anarcha, Betsy, and Lucy, were operated on multiple times, including 30 separate surgeries on Anarcha alone. The operations were performed without anesthesia, as Sims believed slaves were able to bear great pain due to their race.

Garner’s piece is built around a discarded wedding dress, dyed blood red and surrounded with pearls, crystals, and hair weave. With knowledge of the history referenced in the piece, it’s difficult to even look at. And hung in front of a shiny, mirrored surface, the viewer not only sees the piece but becomes a part of it.

Scarville’s work uses commonplace objects, often in large photographic prints with muted colors, to suggest the lives of the people who used them. In a self-portrait, she drapes herself in the clothing of her deceased mother to rekindle a human connection with the departed. “Lucid” performs a similar exercise in three dimensions, with two chairs connected by yarn and covered with discarded clothes.

Mounting the exhibition with Garner and Scarville’s disparate work together allows connections that deepen the meanings of both artists individual visions.

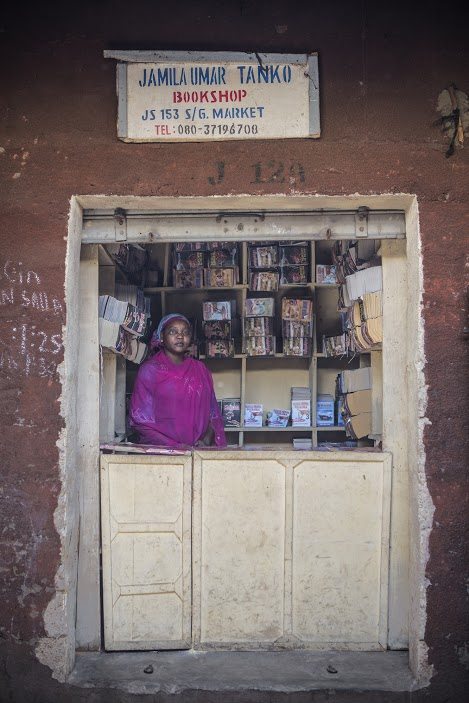

In another gallery, Glenna Gordon’s photographs are centered on the creation of “books of love, (littattafan soyayya)” paperbacks written and assembled by hand by Muslim women in Nigeria. A unique style of romance novels, the books often document social practices unfamiliar to Westerners, as revealed in the translated synopses included alongside a display of the colorful covers of the books.

Gordon’s pictures often focus on individual women, like Jamila Umaar Tanko, who opened a tiny store, the size of a closet, to sell littattafan soyayya when she discovered male shopkeepers did not pay her properly for her books.

Another photo shows a mass wedding organized by the Hisbach, the Islamic morality police, for widows and divorcees.

Gordon said she works to avoid using the work to either judge or explain the society reflected in her photos and the culture they depict. Instead, they offer a tantalizing glimpse and evoke a desire to better understand the complex limits and possibilities of the women she depicts.

Theresa Chromati’s colorful work begins with the recognition of the enjoyment of tea drinking as the passive residue of colonization. But it also celebrates the practice as the possibility of solidarity and human connection. In her large, cartoon-style illustrations, masked black figures are dressed in teacups and teapots, lifting a massive carton of milk, dancing joyously or posed in postures of defense.

MoCADA, the Museum of Contemporary African Diasporan Arts, is open Wednesday through Sunday. (Noon to 7 PM on Wednesday, Friday and Saturday; Noon to 8 PM on Thursday; and Noon to 6 PM on Sunday).