The Stained Glass Maker Of Marine Park, Sarah Herbst

by Vanessa Ogle

The bright colors in the bar might be the same bright colors in the synagogue. Sarah Herbst, a third generation stained glass maker at All American Art Glass, has seen her family’s glasswork in a variety of places.

“I used to take a picture whenever I’d see one,” said Herbst, whose family has been creating and restoring glass since the Great Depression. “But there were just so many.”

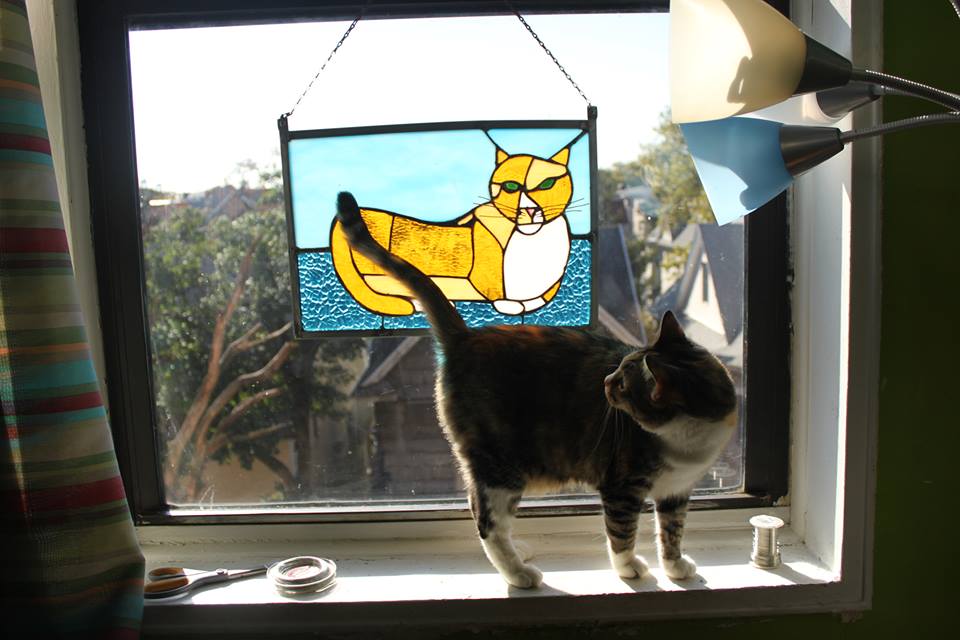

Though some of the standard images—multi-colored flowers or bright circles—she sees around were created by other glass makers, Herbst can usually tell her grandfather’s style: thick but breezy, even lines curving together to make palm trees, windmills, lighthouses.

Though Herbst’s great-grandfather was the first in the family to get into the glass business as a salesman, it was Herbst’s grandfather, George Herbst, who began creating stained glass artwork. He worked in a glass factory in Brownsville, where he learned Yiddish from the shopkeeper.

Herbst’s grandfather created ventilator-style windows, made lamps and designed cabinets. But much of his work, whether it was creating or restoring, was for synagogues—windows designs and nameplates— like the many on Ocean Parkway or at the Jewish Center of Kings Highway.

“There was actually an article about him,” Herbst said. “The Gentile who worked in the synagogues.”

Her father, Dan, began working with his father, even though initially the father resisted laboring with the son.

“It’s dangerous—glass is heavy, lead is heavy,” Herbst said, noting the different structural issues that can cause problems, like worn walls.

But Herbst’s father was persistent. He started helping his father when he was a teenager, assisting in making broken stone windows. The glass shards—pretty but often discarded pieces that were too small to use for most projects—were merged together, the opaqueness of the different pieces shining bright.

“These days, people buy doors with pre-manufactured glass,” Sarah Herbst said in a matter-of-fact tone that neither endorses nor disavows the inevitable changes that have occurred throughout the more than half century of business.

Herbst, though, does things the old-fashioned way.

“It comes in handy when you’re restoring because we literally will have the same glass.”

Even as a child, Herbst was helping her father with their business—even if it was just lending him her art supplies, especially the stencil lettering kits he’d end up using as a guide for stained glass nameplates. When she was in high school, Herbst would use some of the stained glass décor to make pendants or jewelry, including an unusual-looking jewel—white but a shimmery gold in the light—that turned out to be a piece from Tiffany Studios.

Eventually, Herbst began cutting glass and only needed to learn a few of the most important lessons, like not clearing out leftover glass pieces stuck in a pair of pliers with her bare fingers. It took her only one time to remember that one.

Though now, it’s some of the modern-day challenges for Herbst that can still sting. Herbst uses lead and won’t install a piece, like a broken stone window, in a home that has either children or a person with respiratory problems. And though she sometimes uses the Internet to market her art, there is often more pitfall than profit. Sites like Etsy mean expensive shipping and Craigslist customers have too often become synonymous with scams.

Herbst is able to find work in many religious institutions since, typically, many look for the old-fashioned style, consistent with what she—just like her father and grandfather—is able to produce. Recently, Herbst found out her father did glasswork for the synagogue where her maternal grandparents, who are Jewish, were married.

The studio, located in Marine Park, is in her father’s backyard.

“Born and bred,” Herbst, who has lived in Gravesend, Marine Park and now in Kensington, says of her home.

As Herbst flips through one of the thick photo albums that holds the blues, greens, yellows and reds—like the rose, more permanent than any pressed ones, her father made for mother when they first started dating—it’s clear that their art has become not only part of their past but also, of Brooklyn’s.

“It’s interesting. In some senses, living history,” she said.