“The only way we got through that first night was with my daughter on my chest” – Making Room For Fathers At Hospitals

FLATBUSH – My husband was snoring through my contractions, but that was OK with me. We’d gotten to Kings County Hospital in Flatbush at 10 am the previous morning to let doctors try to coax out our overdue baby. This had been a slow, boring process, during which we’d watched 6 episodes of Jane the Virgin and had been visited by a nursing student who showed up at my door and announced that she had been told to “come, watch a birth.” “Nothing’s happening here,” I had told her. I hadn’t given birth before, but even I could tell that this baby still had little interest in joining the world.

“Well, I have to stay for 2 hours,” she’d said, clearly a little miffed. And she had stayed, sitting in a corner, watching us watch Jane the Virgin.

So at 2 am, even though the contractions had picked up, I thought it made sense for my husband to get some sleep. But before he did, I made him a deal: if our daughter was born the next day, then he would take the bulk of the work that night so that I could finally sleep myself. “Obviously,” he said.

That way of proceeding, however, didn’t seem at all obvious to Kings County Hospital. Instead, mere hours after birth, visiting hours ended and my husband was sent home. Only I was allowed to spend the night.

The reactions I get to that part of the story depends on where the listener is from. People who grew up in any of the five boroughs of New York City often look at me like I have just complained that my birth experience compared unfavorably to Beyonce’s. “Well, yeah,” they say. “You didn’t pay for a private room, right?” People in Seattle, where I grew up, and nearly everywhere else, are outraged.

When I learned that my husband would have to leave just three hours after my daughter was born, I sobbed. I couldn’t even stand up without blood pouring out of me. How was I to change her diapers, or even pick her up to feed? By that point, I had already been awake for 34 hours. I kept sobbing, intermittently, the rest of the night. (A nurse asked me if these were “tears of joy” at being a new mother. They were not.)

There is no available centrally collected data that I could find about how many hospitals have this policy, but anecdotally, it appears that New York City is far outside the norm in not allowing every parent the chance to care for his or her infant during the first night of life, whether or not he or she paid for a private room.

After looking at dozens of hospital policies from around the country, and surveying a group of 50 mothers from across the U.S., I was unable to locate a single hospital outside the five boroughs or Long Island that did not automatically allow all parents to stay with their newborn overnight. The Institute for Patient- and Family-Centered Care had no information about the issue, nor did Judith Walzer-Leavitt, author of Make Room for Daddy: The Journey from Waiting Room to Birthing Room, who wrote a comprehensive account of how a woman’s partner has come to be an expected part of his or her child’s birth.

At Brooklyn Methodist Hospital in Park Slope, fathers are only allowed to stay if you pay for a private room: $350, not covered by insurance. At Mt. Sinai West in Manhattan “Visiting hours for birth partners not securing a private room are 7 am to 10 pm.” (A woman who gave birth there told me that even if you’ve paid for a private room, you might not get one unless you remind the hospital staff while you are in labor that you paid for it.) Also, a private room will run you $900, not covered by insurance–slightly more than the listed price for a room at the Plaza.

Maimonides, in Borough Park, the largest hospital in Brooklyn, allows someone to be overnight with you–just not the father: “For the comfort of our patients we can permit an overnight stay for one female support person per patient.”

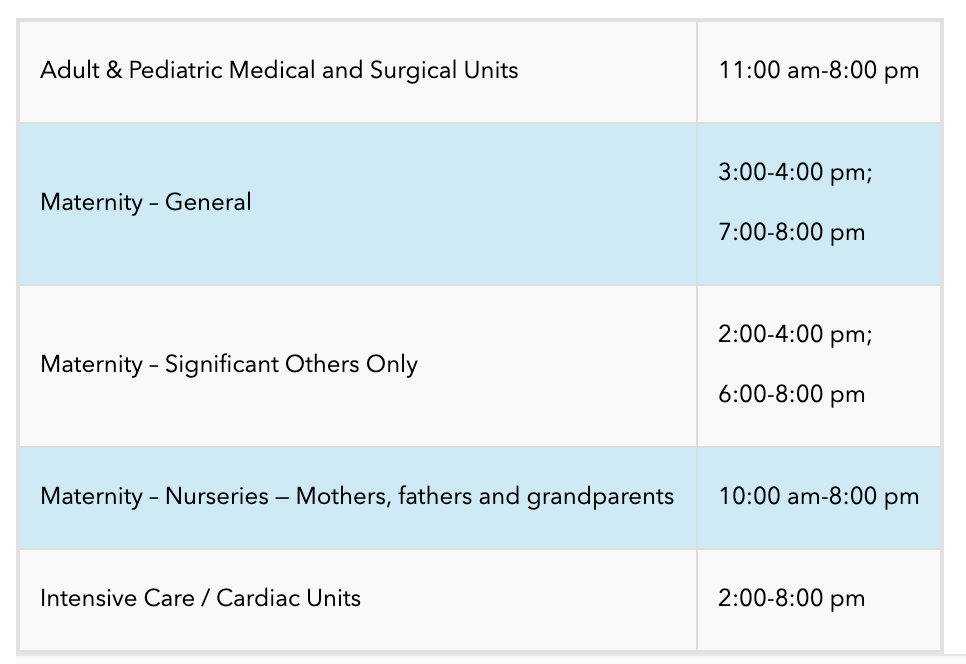

There are even discrepancies at hospitals within the NYC Health and Hospitals network, which don’t have private rooms at all and primarily serve lower-income residents on Medicaid. Two of its three Brooklyn hospitals–Coney Island and Woodhull–allow fathers to stay overnight–the one where I gave birth (Kings County) did not. According to their own website, my former hospital’s policies have gotten even more restrictive since I gave birth there in 2017–Kings County Hospital’s website now states that it allows significant others in the postpartum recovery area for only four hours a day: from 2-4 pm, and then again from 6-8 pm.

New York Health and Hospitals said in an emailed statement: “There are incredible benefits to creating an early bond between a newborn and its family, which is why each NYC Health + Hospitals facility has been moving toward family-friendly visiting hours and visitation policy.” The spokesman stated that Kings County Hospital was “in the process of updating its website to reflect current policy” that fathers could bet at the hospital between the hours of 8 am and 11 pm. (Though this was described as a “change” this was identical to the visitation policy in place during my stay in 2017.)

Several Brooklyn mothers who chose to pay for private rooms to allow their partners to stay described the profound impact that it had on their hospital experience. Diana Trautner, who lives in Brooklyn and gave birth to her daughter at Mt. Sinai West in 2017, described herself as “uncomfortable with this idea of tiers of care…because to me having my partner there definitely impacted my care.” She described her partner as a “24/7 aide, emotional support, the person who reminded the staff I needed medicine and most importantly my daughter’s caretaker.” Another Brooklyn resident, who didn’t want her name used and who had her daughter at Methodist, told me that she felt it would have been “cruel and unusual and traumatizing” to have her husband forced to leave her alone to care for her daughter overnight after she had just given birth.

The lack of access to private rooms also impacts families that are formed through surrogacy or adoption. Today, the person who gave birth may not be a parent at all — two men, for example, may become the only legal parents that a child has. Brian Esser, an attorney who represents adoptive and surrogate parents in Brooklyn, noted that under New York law, even if the birth mother or surrogate has consented to an adoption, her rights are not automatically terminated by signing the papers. For the two (or often more) days that a newborn stays in the hospital, the child’s intended parents are thus in a kind of legal limbo, which different New York hospitals handle different ways.

Esser has found that while some hospitals are accommodating, others have little knowledge about adoptive parents. He noted that, in his experience, “birth mothers who have made the decision to choose a certain family to adopt their infant are invested in having the adoptive parents bond with their child.” It sometimes falls to the birth mother to advocate for the adoptive parents, however, and it is far from a guarantee that they will be able to stay with their child full-time. New York Health and Hospitals did not respond to questions about whether they had a policy that ensured that adoptive parents or parents who used a surrogate were able to care for their newborn.

Another complicating factor is that in all NYC hospitals, the standard of care is that the new baby “rooms in” with the mother rather than staying in the nursery. This practice is encouraged by the World Health Organization’s Baby Friendly Hospital Initiative. To be accredited by the WHO as “Baby Friendly” — a designation that certainly sounds desirable — 80% of mothers must “report that since they came to their room after birth. . . their infants have stayed with them in the same room day and night.”

A mother who asks to have her baby cared for in the nursery should be “educated about the advantages of having her infant stay with her in the same room 24 hours a day.” The word “father” appears exactly twice in the 38-page document that sets out the extensive criteria for Baby Friendliness.

One of the times the word is used is in a discussion of the importance of skin-to-skin contact for infants, which states: “In the case of incapacitation of the mother, another adult, such as the infant’s father or grandparent, may hold the infant skin-to-skin.” Esser notes that this particular push–to eliminate nurseries, and to assume that the biological mother is the child’s only caretaker–is problematic for surrogate or adoptive families. “It’s clear,” he said, “that they’re giving absolutely no thought to adoption or surrogacy in those contexts.”

Esser notes that for adoptive and surrogate families, who already face barriers, “The way adoptive parents and intended parents experience those couple days in the hospital really can help to create that sense of stigma.”

There is growing awareness that fathers who take paternity leave are more involved in their child’s care when that leave is over–those few weeks make a difference in enabling parents to have egalitarian relationships. In New York City, however, the mother or possibly a nurse will be the only one doing feedings or changing diapers nearly half of the child’s first 48 hours.

Nick Thalhuber, a Brooklyn father of a two-year-old, who was able to stay with his wife and daughter, described the practice of having mothers be solely responsible for caring for their children after giving birth as “insane:”

“The only way we got through that first night was with my daughter on my chest.”