Six Feet Of Food Cooked In 675 Square Feet: Brancaccio’s Food Shop Celebrates Five Years On Fort Hamilton Parkway

Joe Brancaccio has been busting balls at his shop at 3011 Fort Hamilton Park for exactly five years as of today. When you walk into Brancaccio’s Food Shop to grab one of the sandwiches from a growing list, a roast chicken that was announced with a thousand exclamation points on his Facebook page, or any other number of the delicious, comforting prepared food items that are packed into the small space, the owner is there to greet you, exchange barbs joke for joke, and ultimately make sure you walk away with the best version of his food possible. The first time you’re there, you’re a regular; if you return again, you’re basically family.

Not that he thought there’d be regulars when he first opened on January 21, 2010 — or any customers at all, frankly.

“When I was going to buy this spot I did a head count outside the place with a counter,” he says. “‘Could this be a customer? Is this your demographic? Could they dig your food?’ I didn’t need a clicker the second day — the first day, I couldn’t count 10 people that walked in front of the store in an hour.”

Still, the space, nestled on what was then a fairly empty block between East 2nd and East 3rd Streets, seemed meant for him, and he was ready to take it. Kidfresh, the organic prepared foods start-up he’d been working at as a chef, had just closed its store, and he was ready to do his own thing. Driving around looking for the perfect location became his full-time job, until he found himself cruising up East 3rd Street from 18th Avenue, where he’d just passed his grandparents’ old house.

“Whenever my whole family gets together, they always speak about the East 3rd Street house. So I’m like, ‘East 3rd Street, East 3rd Street,” Brancaccio says. “I take it straight up, and there’s this strip of storefronts that are untouched, and I’m like, ‘Fuck, why has no one taken this?’ There’s a for sale sign in my shop — I’m not talking about a real estate sign, I’m talking hand-written on cardboard — and I’m thinking ‘Wow, I know this spot, my mother sent me the listing for this.’ So I jump out. There’s garbage piled everywhere. It certainly wasn’t what it is today. I get out and I’m like, let me make the call, let me see.”

And by May, he was in contract on the space, a former sushi restaurant — but, as these things go, he didn’t go into closing until September, which gave him time to assemble a small team and design an initial menu, though it wasn’t without its difficulties.

“People who cook for a living, they spend a lot of time going hungry,” he says. “That was a hard summer.”

But as intimidating as it was, he’d been ready for it for years. One of the inspirations for the design of Brancaccio’s Food Shop is the summer kitchen of his other set of grandparents (the other inspiration, sometimes: his teenage bedroom), who lived in a house in Dyker Heights where the family had to show up early at Christmastime to beat the rush of holiday light gawkers. That basement space was where he basically started a lifetime in the kitchen — he and his younger sister Barbara and their cousin Stephen would play restaurant down there, among the various “props” on hand from his grandfather’s furniture business. His first foray into actual cooking, at around the age of nine, was about as ambitious.

“The first time I turned on a stove and cooked something it was wither one of two items — French toast, or you know those cinnamon buns that come in the canister that you bang against a counter to open? That was probably the first thing,” he says. “Those things were so fucking awesome. They came with a can of fondant — I could eat that with a spoon, wow. So that’s where that started. But I didn’t take it seriously until after I graduated college.”

Though he’d bussed tables as a kid, he ended up studying finance and economics at St. John’s University. Throughout that time he knew he wanted to own a restaurant, even before he’d really worked in one. Then a friend introduced him to the owner of Urbino, an Italian restaurant on Carmine Street, who invited Brancaccio to come into the place to see if it was really for him.

“It’s not that long ago — but seems like yesterday for me, 20 years ago — you didn’t really go into this business if you weren’t born into this business,” he says. “Or you didn’t hang very long. It’s not just that 90 percent fail rate, it’s like, ‘What did I get myself into, I can’t work six or seven days a week, I can’t work these hours.’ How long can you come home at two in the morning before you’re totally strung out? It’s a hard life.”

The allure of that lifestyle proved too hard to resist for him, though, and every time he passed a restaurant that was about to open, the windows papered over and promising endless possibilities, it solidified everything he’d always known he wanted.

“That excitement I used to get when I saw newspapers go up over a window and know a new place was coming in and I would think, ‘I wish that was me building that,'” he says. “I was so jazzed for whoever was papering up windows.”

So he rounded out his “mathematics of cooking” by attending the Institute of Culinary Education, did his externship at Montrachet, then worked as a chef to help reopen the massive Lundy’s in Sheepshead Bay, where he and his coworkers may have pursued the excitement of the kitchen life a bit too hard.

“When you get real into it, there’s the romance of the business, the addictiveness, the after-work stuff,” he says. “That was my first taste of the subculture that could burn you out very quickly. I lasted three years — you could wreck your life in three years. I needed to stop that and think about working days.”

That’s when he took a job at Agata & Valentina, where he worked for about nine years, and where he ultimately began building the base for what his shop is today.

“One of my prime philosophies is that you have to do something new in this business,” he says. “Prepared foods is not new by a longshot — the people I worked for [at Agata & Valentina] for 10 years invented the concept as far as I’m concerned. But it was new in this area. And I just wanted to cook fresh food every day, keep it small.”

That’s the equation that’s helped him build a successful small business, which, he says, has only happened because he’s cooking from the heart.

“A place works when it’s true to yourself and it’s true to who you are,” he says. “People see if you’re perpetrating a lie. My place works because I’ve been cooking food like this for 15 years. It’s true to who I am.”

He had toyed with the idea of a sit-down restaurant, but as a self-described control freak (to this day, nobody answers the shop phone, which goes directly to his cell, but him), he wasn’t interested in making anything bigger than what he ended up with.

“I didn’t want to deal with front-of-house staff, the moving parts of a restaurant,” he says. “I cook. I’m not a server, I’m not a wine guy. It’s more people, more people that are out of control (mostly). It’s more difficult for a controlling person to deal with people who are out of control. I just wanted to deal with cooks, because that’s what I’ve always dealt with.”

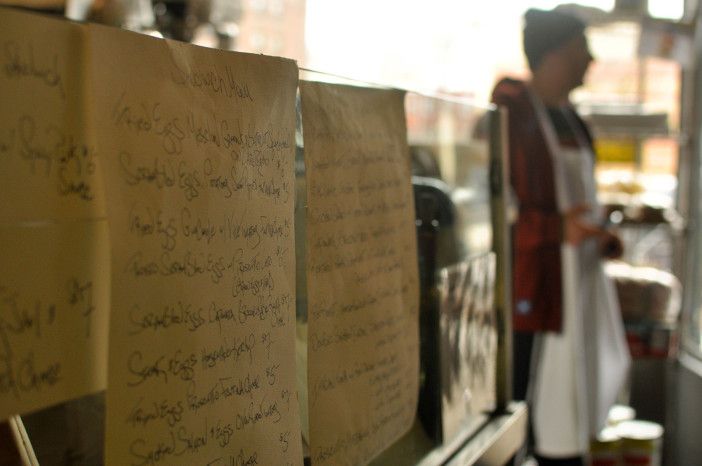

So in his shop, which is around 675 square feet, on a busy day it’s him and six employees shuffling around a few hot plates (there’s no gas line in the space, which leads to an “astronomical” electric bill and some blown-out breakers in the summer) in a nicely conducted dance that results in “six feet of food,” he says. “That’s what it comes to, a six-foot showcase.”

In the five years since it opened, that six feet of food is basically the only thing that’s changed, as the menu has grown and continues to evolve. And every day it’s been open, Brancaccio has been there to make everything is how he wants it to be — he says he hasn’t had a vacation in about six years, and looks forward to major holidays that fall on a Monday or Wednesday, on either side of the shop’s regularly closed Tuesday.

“At the end of the day, if something goes wrong, there’s no one you can point the finger at but me. I can’t blame anyone for anything but me,” he says. “Even though there are very capable hands in the kitchen, it needs to be right. A chef can’t manage from outside the kitchen. Something aways happens, something always goes wrong.”

And that’s part of the reason why he’s never opened a second space, though opportunities have come in regularly.

“The offer’s been there a bunch of different times,” he says. “I think I know the direction I’m headed in 2015 — I’m going to work on something, but it’s going to executed from my kitchen, because I can’t do it any other way.”

The neighborhood wouldn’t have it any other way, either. Though it may have seemed like a bit of a ghost town on that first day he stood outside counting pedestrians, by the time he opened, his local, soon-to-be faithful customers were ready for him.

“I put the papers up in my windows the day I bought it, because of course that’s what I wanted to do,” he says, explaining the excitement of finally being able to be the guy behind one of the new places he’d always been curious about and psyched for. “I was probably wearing a suit at the time, I came right from lawyer’s office, went to Home Depot and bought butcher paper and put it up and was like, ‘Wow, okay, people are going to know, I’m going to start to build.’ And no one said anything the whole time! Then I took the paper down and the floodgates opened.”

Brancaccio clearly appreciates his customers, and knows how lucky he is to remain in business in New York City for five years, but he admits that some of that initial sheen has dulled a bit — though he knows how to find it again when he wants to.

“The realities of the food business are harsh,” he says. “That romance, you can’t lose sight of what attracted you to it. You have to tell stories like this. The only thing that keeps you going is to always remember what you liked about it to begin with. That kind of eases the pain in writing the checks, and there are a lot of checks to write.”

And if we’re lucky, that big picture that he’s always keeping his sights on will remain on Fort Hamilton Parkway for a long time to come.

“Can I make it 20 years? I don’t know,” he says. “If I could do this ’til then, if someone said, ‘You could keep what you’re doing or branch out,’ I would keep what I’m doing.”