Residents Don’t Like The Smell Of Coney Island Creek Resiliency Study

Residents scorned some of the initial assessments presented on Thursday for a flood barrier in Coney Island Creek, arguing the city was pushing a proposal that did more to boost tourism than address the waterway’s longstanding pollution problem.

“I really think this is a boondoggle of monumental importance,” said Ida Sanoff, a Brighton Beach resident and executive director of the Natural Resources Protective Association. “Every meeting I’ve gone to, they’re pushing one thing and one thing only. And that’s the eastern floodgate. Why? Because they can also put a bike path over it and more people can come into Coney.”

Representatives from several city agencies, including the New York City Economic Development Corporation (NYCEDC) and the Mayor’s Office of Recovery and Resiliency, came to the MCU Park Baseball Gallery to discuss their study on building a flood barrier in Coney Island Creek.

A spokesperson for NYCEDC said the goal of the study was to “to create a shared vision between the community, the City, and our State and Federal partners for how to protect the communities around Coney Island Creek from storm surge and sea-level rise.”

Throughout the meeting, presenters stressed the study was only halfway complete and none of the proposals were near ready to be finalized.

“We’re not at the stage right now where we have a specific concept to deliver to you,” said Elijah Hutchinson, NYCEDC’s assistant vice president for resiliency. “We’re here to talk about flood protection and to start to get your feedback and ideas as to how we can start to put together a plan.”

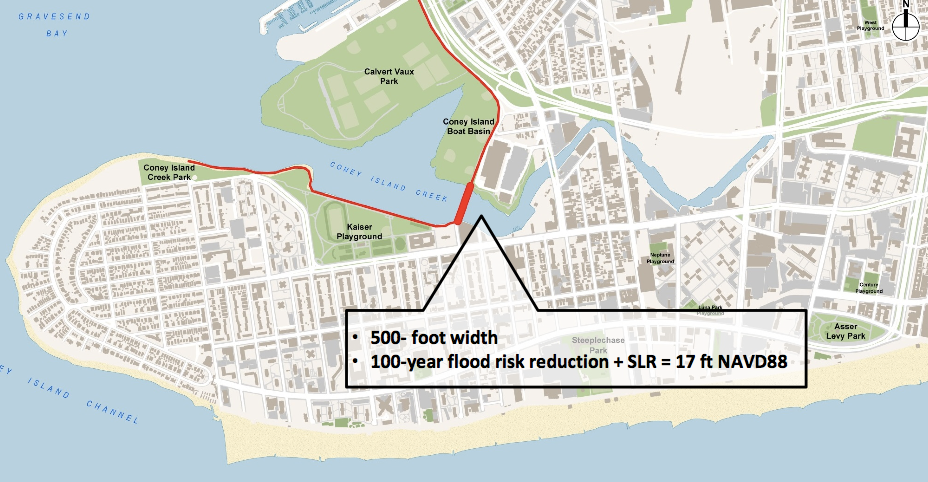

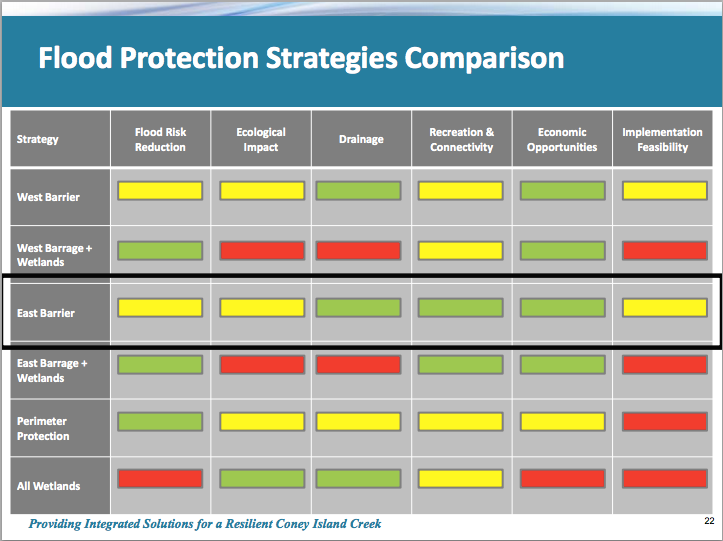

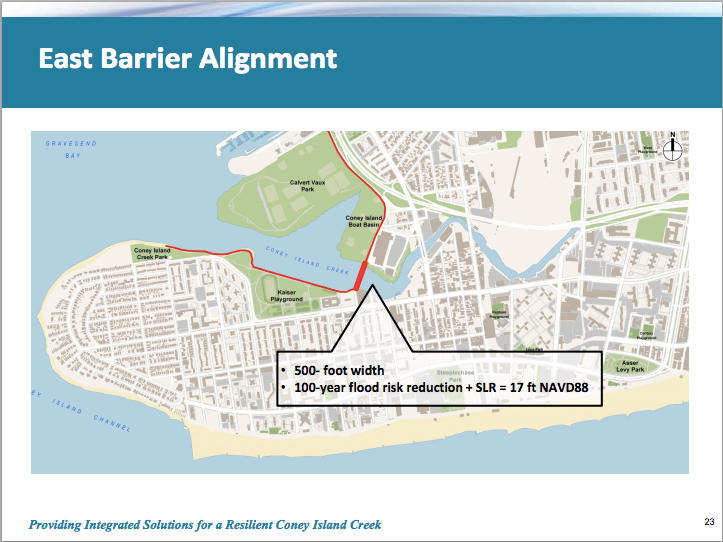

However, the presentation repeatedly identified the East Barrier proposal, which involves building a mechanical gate across a narrow section of the creek near West 22nd Street, as the most feasible option. The floodgate would remain open to allow water to flush out to sea and would only close during extreme weather. The land west of the barrier would be lined by walls built to withstand a so-called 100-year storm, the representatives explained.

Some residents at the meeting worried the proposal did little to address the creek’s pollution and drainage problems. A 2014 study concluded Coney Island Creek was the most fecal-filled waterway in New York City due to raw sewage and storm runoff that gets dumped there when the city’s antiquated sewer system overflows.

“It seems like what they’re proposing is to build this bathtub,” said Coney Island resident Marissa Solomon, who lives near the eastern end of the creek. “How are you going to get rid of the water that’s sitting behind this barrier when it’s closed? And how are you going to make sure that water isn’t filled with all this toxic muck that’s lying at the bottom of the creek?”

The city has begun a multi-billion dollar effort to upgrade its sewer infrastructure, which is expected to reduce the amount of sewage spilling into Coney Island Creek by 90 percent. But that project will do little to decontaminate the sediment resting on the creek bed.

Julie Stein, northeast stormwater lead at HDR, Inc., an engineering firm involved in the study, said researchers had looked at every inch of shoreline along the creek and made environmental considerations a priority.

“We wanted to prove that a barrier would not exacerbate water quality because that’s key to long-term ecological health,” she said.

City Councilman Mark Treyger, who represents Coney Island and attended the meeting along with Congressman Hakeem Jeffries, said any final proposal produced by the study must recognize the environmental hazards that exist in the creek.

“There is no question that Coney Island Creek has been historically neglected. There are very bad things down there,” he said. “It is my hope and expectation that the final outcome of this plan will involve an environmental cleanup of Coney Island Creek. Ultimately, it is science, sound science, that should govern and dictate this process.”