Protest Groups Clash In Fort Greene Park Over Burning Of The U.S. Flag

The planned flag burning of both American and Confederate flags at Fort Greene Park on Wednesday night, July 1, did, in fact, happen, although not where protest organizers had said it would happen and not without angry and impassioned counterprotests from flag-waving New Yorkers who ended up vastly outnumbering and out-vocalizing the anti-flag protesters.

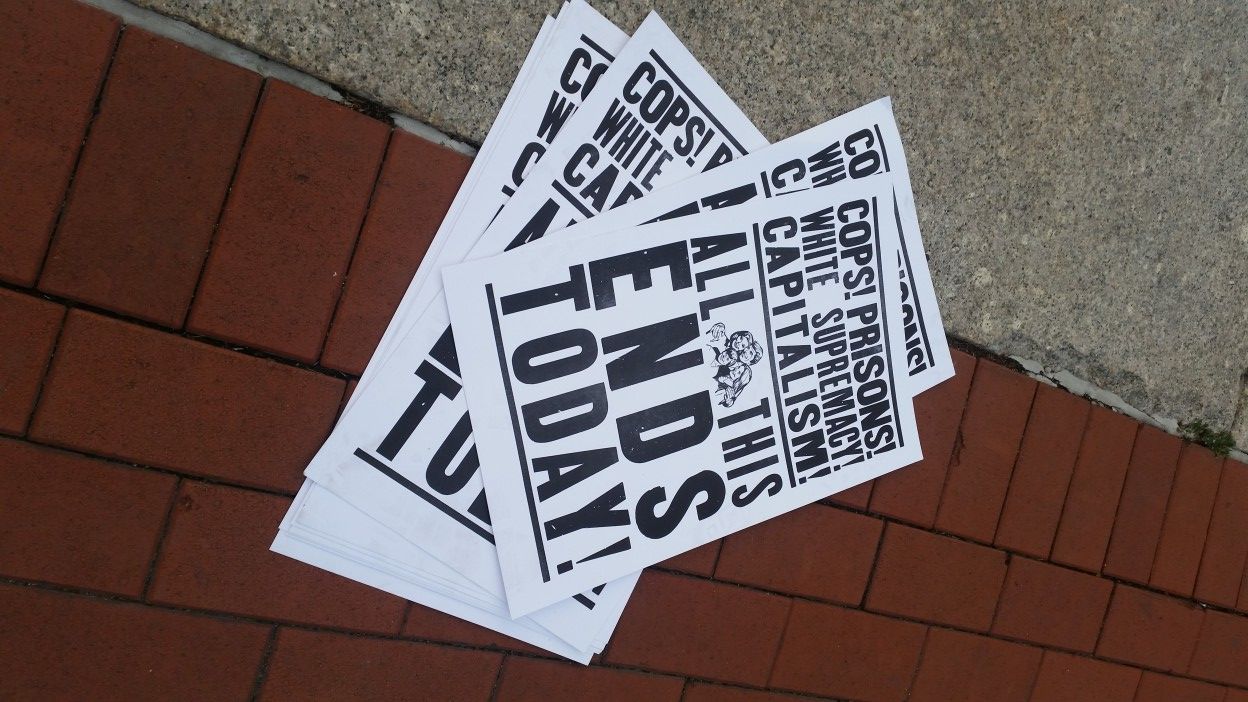

Chants of “USA! USA!” and “If you don’t like it, then leave!” punctuated the air at the corner of Myrtle Avenue and Washington Park, where camera crews, protesters, and counterprotesters converged in anticipation of an event, entitled “Burn The American Flags,” announced earlier in the week by an activist group called Disarm NYPD.

“I have my beliefs about what the flag represents — a country that started by escaping a tyrannical country for a better way of life,” said Joey Reichling of Glendale, Queens, who came clad in an American flag bandana and scarf. “I don’t want people to burn the flag. If they don’t like it here, then they should leave. Our government has its flaws, obviously, but they’re going about it ridiculously. This isn’t a flag of race; it’s a flag of a nation.”

The first clash of protesters occurred within minutes of the 7:30pm protest start time, between pro-flag counterprotester Diane Atkins of Bay Ridge and fellow Brooklynite Victoria Phillips, who while not part of Disarm NYPD, supported their stated mission of demonstrating “for the Charleston nine and all of those killed by racist violence in America” and criticizing the flag as “a symbol of oppression and genocide” that is part of “a consistent pattern of state-sponsored terrorism and racialized dehumanization.”

“My mother’s life was shed for this country. She is in a military cemetery. But you don’t get policed the same as I do, as my son does. I don’t have the same rights,” shouted Phillips through the crowd that surrounded her. “My 10-year-old son was chased by a police officer who told him to tell him what gang he was in. He said he’s in no gang! And he didn’t believe him. The flag doesn’t hold the same symbol for me as it does for you.”

In response, Atkins shouted that “we fight like family, but we always come together. . . [These protesters] are irrelevant. . . I don’t care what you think; this flag, people in our country died to protect.”

Soon, the argument got so heated, with more pro-flag counterprotesters interjecting with their own criticisms and admonishments for Phillips that “that’s a lie! That’s a fake story,” “America isn’t about racists,” and “if you have a problem with the government, take it out of the government. This flag is on caskets. You don’t like this country, then leave. This is my country.”

Eventually, retired U.S. Army veteran Mark Brummitt, dressed in camouflage fatigues and leading his canine Kita, by a leash, managed to break through the raucous circle and stand between the women. The duo had a calming presence, at least for a short while.

Brummitt, a 13-year-veteran who, after service, served as a pastor in Missouri and now lives in New Jersey working on “Who’s Saving Who?” — a nonprofit that works to provide disabled vets with rescue dogs — told Phillips that “it doesn’t have to be like this. . . This is where we come together and start to move in the right direction. Instead of coming and burning flags, we need to talk.”

“I’m here today for my human rights. Burning a flag won’t fix it, but when we do things like this and come together and march, you get national attention,” insisted Phillips. “More people need to educate themselves and have this constructive conversation.”

Reflecting on their dialogue, Brummitt told us that “we [as a society] need to break through the hate and fighting to address issues instead of burning the flag. The flag represents our way of life, everything we stand for, her opinion, everything to this point.”

As Atkins, Phillips, Reichling, Brummitt, the assembled media and onlookers stood at Myrtle and Washington, a wisp of smoke appeared above the tree line further inside the park, triggering a mad dash up the hills and towards the Prison Ship Martyrs Monument, where a small barbecue grill bowl had been set up at the top of the steps and an American flag was in mid-burn.

As noted by CBS2 News, “one of the flag-burning opponents, John Carroll of Ridgewood, Queens, managed to pull the burned flag out of the flames. . . They’re losers looking for a few minutes of fame. And they didn’t even have the guts to do it down there where they were far outnumbered, and I got here before they destroyed it completely.”

“It was a small dinky fire and I could barely make it out,” said Joshua Trust of Bay Ridge. “The cops were not even here. The counterprotesters hadn’t gotten here yet. I’m neutral [but] it was sad seeing anything burn.”

In addition to Carroll, a group of bikers from the Hallowed Sons Motorcycle Club also arrived in time to stop the flag-burning. While Carroll and a biker went for the flag and doused the flames, though, the rest of the bikers went for the handful of bandana-masked protesters.

“They took off like little b—hes,” one biker told the New York Post. “They lit the f–king flag and took off running once they got slapped once or twice.”

No arrests were made, although the assembled police quickly interrupted the melee to prevent the protesters from being injured by the counterprotesters. The irony of the police being protested against preventing violence on those who despise them was not lost on some.

“Police and the American flag are separate things,” said Brooklynite Ms. Kat. “Not all police are bad. we need police to keep crime down.”

But for others, being saved by the cops was less notable than the fact that no one was arrested.

“My friend got pushed down. An Army guy has knives. And the biker dudes are armed with hammers,” said a 25-year-old protester who went by the name Sia. “I’ve seen people push cops and get arrested and beat for so much less [than what counter protesters] are doing today.”

Sia, who was there as a protest medic, continued, insisting that “the way I see it is you have to look at the flag as something that represents a whole country, not selected [good] parts. The battle is still being fought to fight white supremacy. It’s an ongoing struggle. The flag can represent whatever they think it represents, but I still think you shouldn’t attack people for freedom of speech. It reflects negatively on them to physically attack people for nonviolent action.”

Hedy Aldina of Sheepshead Bay disagreed, stating that “too many heroes fought and died for it. It’s a horror to have it burned. What our flag represents is the greatest thing. It’s their freedom to do so and my right to try to stop them.”

But anti-flag protester Gabriel from New Jersey responded: “If someone dies for something, does that mean it’s just? The flag represents genocide, the prison industrial complex. . . These people are so sure we’re free and can say what we want, but they’re the ones who are violent. It’s clear who’s hyped on the flag as a drug.”

Amanda Meltzer, 24, of Brooklyn, joined Gabriel as he made his statements, but was shouted down by Atkins as “white trash.” Later, she told us that her belief that the American flag “represents oppression and genocide” began shortly after her family moved from Manhattan to Cambodia.

“I was seven and on a trip to Vietnam, our car was dodging craters. I asked my parents what they were and they told me they were from American bombs during the Vietnam War,” Meltzer said. “At the time, I couldn’t understand how that could be. Why would they bomb Cambodia?”

The idea of childhood experiences impacting life-long opinions and belief systems also resonated with the Bryant family of Fort Greene — all 12 of them — who came to witness the protest, but also to support the flag.

“My kids saw the news about the event and were like, mom, is that okay? Are they supposed to do that,” recalled mom Kisha of her brood of 11, aged four to 22. “They wanted to come. This is the first time they’re seeing conflict up close; it’s a good education for them, to see people try to come together and not destroy us.”

As five-year-old Takieya explained it, “I learned about the flag in school [and] I want to be here because I didn’t want them to hurt the flag.”