NYC Blacks And Hispanics Dying Of COVID-19 At Twice The Rate Of Whites, Asians

By Yoav Gonen, Ann Choi and Josefa Velasquez, originally published in THE CITY.

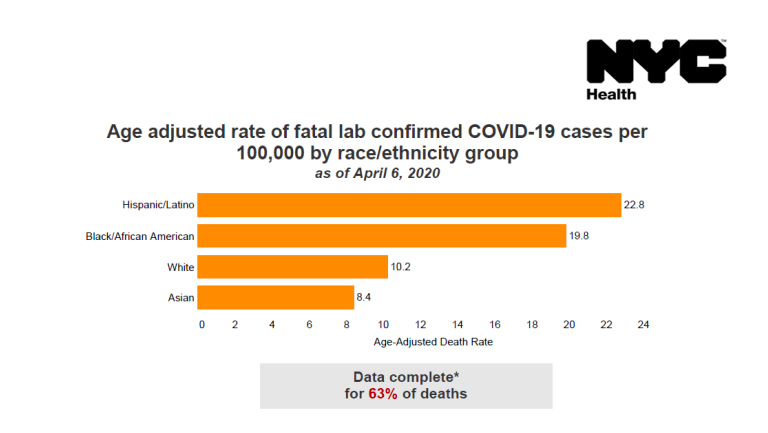

Black and Latino city residents have died from coronavirus at twice the rate of white or Asian New Yorkers, preliminary data released Wednesday by city officials shows.

Latinos have died at a rate of 22.8 per 100,000 residents and black New Yorkers at a rate of 19.8 per 100,000 the analysis shows.

By comparison, whites in New York City with confirmed cases of COVID-19 have died at a rate of 10.2 — and Asians at a rate of 8.4 — per 100,000 people.

As of Wednesday morning, more than 3,500 residents had died of coronavirus, the city Department of Health and Mental Hygiene reported. That figure does not count more who died at home and were not tested for the virus.

Among 2,472 New York City residents who succumbed to COVID-19 through April 6, the Health Department obtained details on race and ethnicity on 1,555.

Of them, 34% were Latino, 28% were black, 27% were white and 7% were Asian, the statistics indicate. A remaining 4% were classified as “other.”

As recently as April 5, Mayor de Blasio called the collection and release of racial and ethnic data on coronavirus fatalities of secondary importance to the task of shoring up public and private hospitals overwhelmed with severely ill patients.

But on Wednesday, following widespread demands from elected officials for data and action, de Blasio struck a different tone — saying he was “very angry” about the disparities and newly taking concrete steps to address them.

“It made me angry to see that the disparities that have plagued this city and this nation, that are all about fundamental inequality, are once again causing such pain and causing people — causing innocent people — to lose their lives,” the mayor said. “It’s sick, it’s troubling, it’s wrong — and we’re going to fight back with everything we’ve got.”

Long-standing Disparities Cited

City officials on Wednesday attributed the discrepancies along racial lines to a host of factors — particularly the prevalence of underlying chronic illnesses among low-income communities and the uninsured.

They also cited patient concerns about seeking medical treatment because of immigration status, anti-immigrant rhetoric across the country and language barriers — issues that can hinder access to health care in the Hispanic community.

“What we may be seeing here played out … is that cycle of those underlying drivers to poor health outcomes essentially on steroids because of the acuity of this virus,” said Dr. Oxiris Barbot, commissioner of the city’s Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

The mayor said he’s planning to double down on providing sufficient resources to the city’s public hospitals, which serve a disproportionate share of low-income people, along with black, Latino and immigrant communities.

He cited Elmhurst Hospital in Queens — which was the first of the city’s medical institutions to require significant outside assistance to keep from being overrun during the current crisis.

More Testing Promised

Gov. Andrew Cuomo released the city race and ethnicity data Wednesday as part of a new statewide tally.

He said that the state would be doing “more testing in minority communities.”

“But not just testing for the virus. Let’s actually get research and data that can inform us as to why are we having more people in minority communities, more people in certain neighborhoods — why do they have higher rates of infections?” Cuomo said at a news conference in Albany.

The mayor also announced the launch of a multi-million dollar ad campaign in multiple languages to better communicate with the most-impacted communities about the crisis, and a grassroots outreach effort to have healthcare workers relay similar messages directly to people at home.

He said the city also will ramp up ongoing efforts to connect sick New Yorkers to a clinician for a phone consultation through the city’s 311 call center.

Public Advocate Jumaane Williams, who has been calling for the city to provide the data by race and ethnicity, said neither the numbers supplied nor the city’s response goes far enough.

“We need to know the racial breakdown in rates of testing and of positive confirmed cases to find and correct these clear failures,” he said in a statement. “The coronavirus may not discriminate, but the response, or lack of response, clearly has.”

Williams has called for a lockdown of the neighborhoods most affected by the virus, and has requested a reassessment of which businesses are deemed essential enough to remain open amid widespread closures.

The high rate of COVID-19 fatalities among Hispanic residents represents an anomaly for a group that has the lowest mortality rate and longest life expectancy rate among all New Yorkers.

THE CITY previously reported that Queens neighborhoods with the highest infection rates are home to many service workers in construction, food and janitorial service.

According to the city’s comptroller’s office, more than 75% of all frontline workers in the COVID crisis — those in health care, grocery, transit and trucking — are people of color.

More than half of health care workers were Hispanic and black. Hispanics make up 40% of grocery, convenience stores employees and 60% of cleaning service workers, the March report finds.

Demand for More Data

City Comptroller Scott Stringer said while the newly released race and ethnicity of those who died provides crucial context, more data is needed.

“This is critical information that underscores years of health disparities in our communities of color that we as a city must address. But there is another level of information we need — we must track hospitalizations and deaths by occupation,” said Stringer.

“Expanded data will make clear just who is shouldering the burden. New Yorkers deserve transparency and solutions that directly address our challenges in real-time.”

Cuomo on Wednesday said he didn’t plan on reducing the number of frontline workers still required to work through the pandemic.

“Frontline workers do have a greater exposure than most people. I think that’s one of the things we’ll find when we do this research on why is the infection rate higher with the African-American community and the Latino community,” Cuomo said.

“I dont think we can reduce the essential services — we’re down to basically food, pharmacy, basic transportation, which frankly is more for our essential workers to get where they’re going,” the governor said.

“I don’t think we’re in a position to say eat less, or use less drugs, or use less health care. I think we have to get through this now and then learn from it and see what changes we can make in the future,” Cuomo added.

The governor’s office did not immediately comment on whether it would be setting up additional testing sites or where they might be located.

Bronx Hardest Hit

State Health Commissioner Howard Zucker on Tuesday attributed the disproportionate rates of COVID-19 among different races and communities to underlying health conditions.

“Some of the communities have challenges with their health in general — they’re more apt to have some of the challenges with asthma and diabetes. And so anytime anyone who has underlying medical conditions ends up with this virus or the other viruses it puts them more at risk,” he said.

The city’s actions to address the disparities follow more than a week of pleas from elected officials and requests from news organizations that the de Blasio administration make data by race and ethnicity publicly available.

A number of states and cities have already released similar data, including Illinois — which provided early data on confirmed cases by race and ethnicity on March 27.

The city’s concrete steps also follow reports by THE CITY that the pandemic is disproportionately killing residents of The Bronx.

De Blasio and Barbot said collecting the data has proved difficult because hospital officials have been too overwhelmed with treating thousands of critically ill patients to focus on inputting data.

Nearly 2,900 coronavirus patients were in hospital ICUs as of Tuesday evening, according to city data.

Barbot said city officials resorted to accessing hospitals’ electronic patient records on their own to collect the information.

“There were technical issues that had to be addressed, as well as legal issues,” she said.