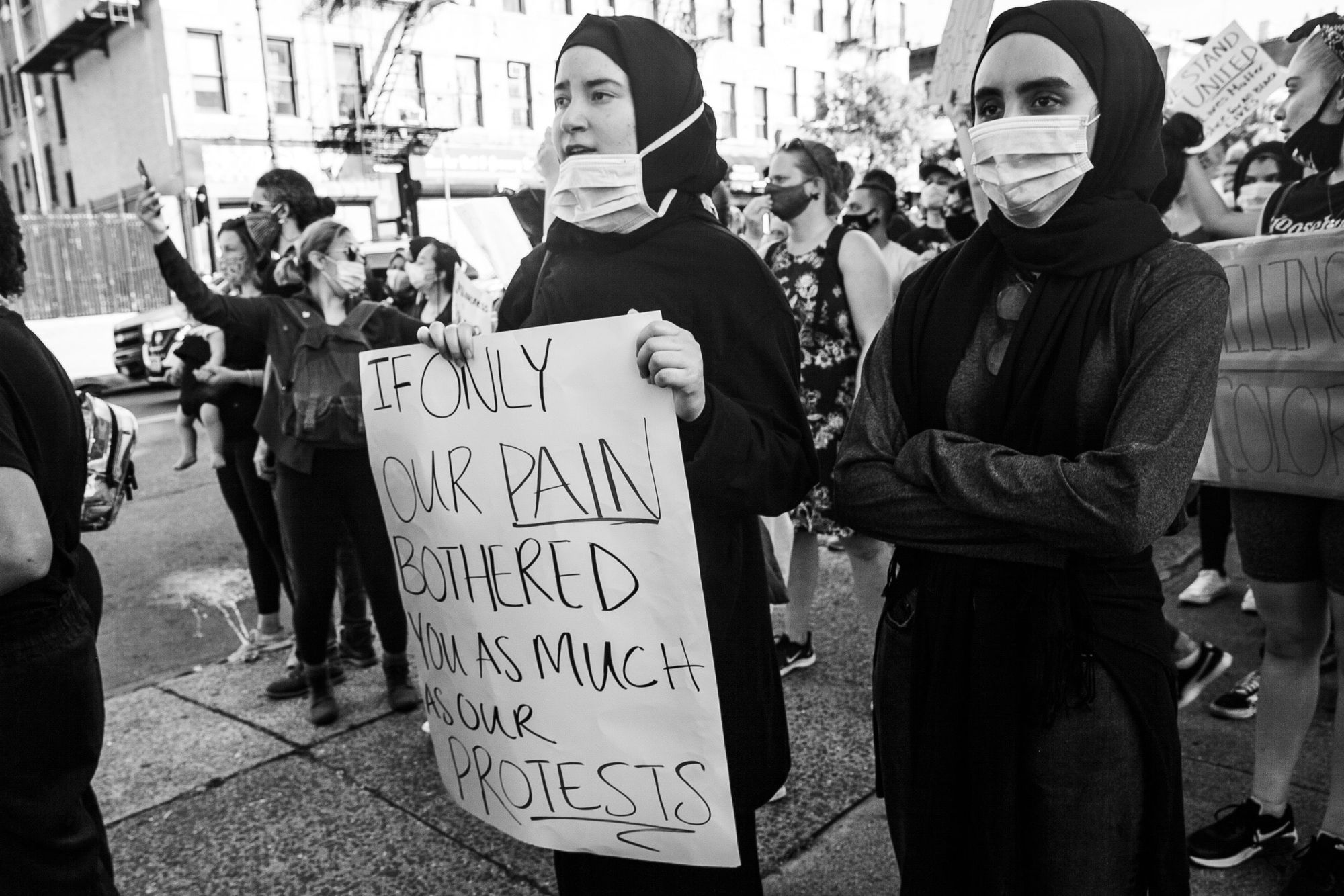

Muslims Against Police Brutality Protest: Bay Ridge To Barclays Center

BAY RIDGE – Three hours, seven miles, and 23,000 steps. That is how long it took about 2,000 people to march from Bay Ridge to the Barclays Center. It was pouring early on in the day yesterday, but by the time it was 4 p.m., the sun was brighter than ever. There were women in hijabs, children perched on their dad’s shoulder, and Black Muslims standing in the front, leading it all. They were chanting “Black Lives Matter” and holding posters that read, “Justice for George Floyd.” It was a peaceful protest. And it was organized by three Black Muslim women: Esraa Elzin, Nicole Najmah Abraham, and Nazahah Booth.

“That’s like the three most hated identities,” Elzin laughed. “Muslim, women, and Black… It’s like society wants to erase us in every form.”

For these women, it was important to hold a protest titled “Muslims Against Police Brutality.” We spoke with them this afternoon about how it feels to be Black and Muslim in America, and the racism they face both in the country as a whole, but more specifically, within the Muslim community.

Booth’s brother and friends attended the many protests that have been happening in NYC these past few days. They told her they didn’t see many visible Muslims. What was the reason behind that? she asked.

“Me being a Black Muslim woman, I represent being Black and being Muslim, so it’s not ok for me to be a Muslim, and my presence as a Muslim is not being seen against police brutality. Our presence as Muslims and as Black Muslims need to be seen,” she said. “A lot of the Muslim community was silent. There wasn’t any speaking out against what happened. There was no action.”

She acknowledged that there is a lot of anti-Blackness in Arab and Desi communities. And so they planned to begin in Bay Ridge to educate those communities, “because there are a lot of Muslims here that are Black and have been here longer than they have. It’s important for those Muslims to know it’s their fight, too.”

“When it comes to masjids, structural changes have to happen. Not only do you have to be anti-police, but you also have to be pro-Black,” Booth said about mosques. “As an organization, it is morally wrong for you to work and uplift police as an institution because it is institutionally racist. And by associating yourself with these institutions, you become a racist institution.”

Elzin works in a predominantly white industry. For her, this week has been exhausting.

“I get it, you’re not racist. But how do we get you to be anti-racism? How do I get you to hate racism the way Black people hate racism?” she said. “How do I get you to speak about it every goddamn day of your life?”

“We’ve moved on from the idea that solidarity is someone who has Black Lives Matter in their bio, to what are you doing, where are you donating… and more importantly, what are the discussions you’re having in your home?” Elzin said. “We know anti-Blackness affects the Muslim community. How do you get them comfortable and actually be in solidarity with us? There’s a whole lot of work you have to do at home instead of putting a quote in your [Instagram] story.”

For Abraham, solidarity is when a person does something not to serve themselves, but because they genuinely care.

“Why does this make Muslims uncomfortable? Solidarity to me is that when it doesn’t serve your own self-interest, are you still putting yourself on the line to empathize with me?” she said. “Or is it going to make this organization look good when we put out a statement?”

Abraham acknowledged that there was some hesitance as they were planning the protest (which they planned in five days, by the way). People seemed to question why there was “Black” and “Muslim” in the name of their protest. And the women themselves wondered if it would be a problem. But in the end, they did not care.

“Why were other Muslims having hesitations? As Esraa said, it’s not a matter of just saying you’re not racist; it’s a matter of becoming anti-racist. That’s from your actions; not from your all Black screens and quotes,” Abraham said. “How can you have empathy for the Black Muslim community if you never made a true connection to that? You don’t identify in so many ways, you never put yourself in a position to identify with us. You’ve never identified with our happiness, with our success, so how can you now identify with our pain?”

During their march to the Barclays Center, when they got to Fifth Avenue, they encountered a group of what they describe as white people standing across the street from a masjid. At that time, a Black brother was sharing his emotions on the megaphone.

“We had a bunch of white people across from us trying to shut us down,” Elzin said. “This is the reality of Bay Ridge. It’s the racism from the Muslim community and racism from white people. I have dealt with all ends of it in this neighborhood.”

When they got to their destination, they prayed Asr. They prayed while non-Muslims stood around them silently and linked their arms to protect them. For Abraham, it was such a profound moment.

“It was a surreal situation to see just so much support. I remember just standing in prayer and feeling the sun in the back. The scenery was great,” she said. “We had the opposing side with police standing and then all the non-Muslims supporting us. I remember all this stillness in the area. During salah, I remember thinking that we’re in a historic moment.”

Both Booth and Abraham did not watch the video of George Floyd being murdered. It hurts too much, they said.

“Seeing Black people being put in that position, I can’t watch that. I can’t even watch movies about slavery. I don’t even condone people sharing that video all over the place because it’s dehumanizing,” Booth said. “It’s very believable that a police officer would kill someone in that matter. You don’t need to watch it. It’s something that is known.”

Abraham agreed.

“I don’t believe in trauma porn, specifically Black trauma porn,” Abraham said. “People are sharing and watching it like it’s entertainment. I don’t condone watching these videos. I did not need to see it to feel the pain that came with it. It was too violent and atrocious and too evil.”

The message these women have for everyone is to reflect. And to the Muslim community, take some action.

“We don’t need to reflect. We have to reflect every single day we walk out with these skin tones and hijab. We need other brothers and sisters to have these conversations and reflections and call people out,” Elzin said. “We can’t do all the work ourselves, it’s exhausting. At the end of the day, if you understand the deen, this is basic information. Protesting is literally part of our religion.”

And like Abraham said, “Our problem is not that [the Muslim community] isn’t doing enough. It’s that they aren’t doing anything at all.”