Mike Cockrill—From Cartoon Paintings To Exploding Businessmen Bunnies

The verve and wit of Exploding Businessmen Bunnies/New York Times, Mike Cockrill’s contribution to The Times, the current exhibition at The FLAG Art Foundation (545 West 25th Street in Chelsea), is clear even to a casual observer.

But for those more familiar with the Brooklyn artist’s forty-year career, connections to his stylistically diverse body of work provide an intriguing backstory for the piece. That story, created in his studio space at Brooklyn’s Old American Can Factory (232 3rd Street at 3rd Avenue, where he’s maintained a studio since 1979), functions as a thumbnail history of the borough’s development as a center of contemporary art.

The direct antecedent for the piece was a series of Exploding Businessmen Bunnies collages that Cockrill had been working on this past year, created with cut up men’s shirts arranged on canvas.

“The subject is a male character,” Cockrill explained. “And the rule is, they have bunny ears. That kind of de-activates the sincerity. They have glasses like me and they are cartoon-like. If you show somebody blowing apart, in an era where people are being blown apart—you can’t be too literal. You need some stylistic relief.”

The series first drew attention in 2016 when curator Donald Kuspit chose one of the collages for a show he was curating with Casey Gleghorn at the Booth Gallery. An open call from FLAG then gave Cockrill an opportunity to do something more with his works.

“Normally, venues of that high level have very closed curatorial programs where they’ll have an elite person bringing a bunch of elite artists in,” said Cockrill. “You stand in the wings and just say, ‘Wow, it would be so nice to be included in a show at a venue like this.’”

For the current exhibition, which runs through August 11, FLAG “put out a call to all artists, because the concept of the show was political,” he said. “The show called for works that used the New York Times as a source, and since the Times is for everybody, they felt all artists should have a chance to submit. I love that idea.”

Cockrill’s inspiration for the piece was to question what was making the businessmen bunnies explode. “It’s like, ‘Why is he blowing up? What’s making us crazy right now?’ Trump. . . and the media. We are suffering from Trump/media overload.”

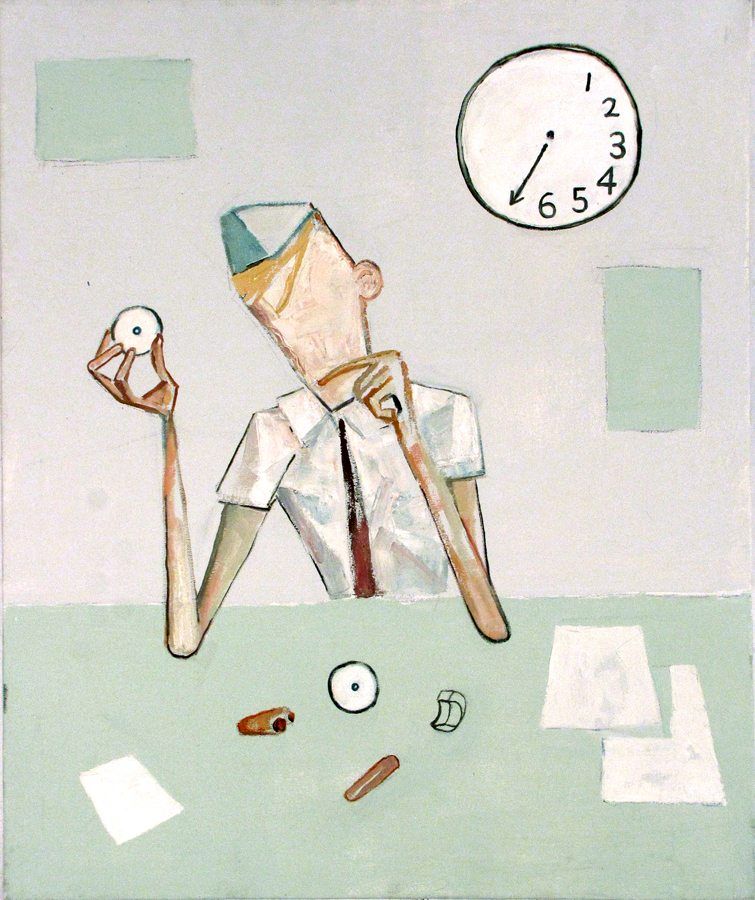

Cockrill traces the businessman back to his 2013 solo show, Existential Man held at Kent Fine Art. His paintings depicted simplified, modernist businessmen who, although they weren’t yet blowing up, had already started going to pieces. “The paintings in my Existential Man series depict a forlorn office drone, often portrayed in white shirt and skinny tie, who is literally falling apart. Even so, he bravely soldiers on.”

To find traces of his current themes, you can turn the clock all the way back to 1979, when Cockrill arrived from the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Art and got himself a studio in Brooklyn “because I wanted to be an artist.” He moved into the Old American Can Factory, where he’s been ever since. “I was living a dual life, working in a shirt and tie at Merrill Lynch by day and making my art by night in a raw loft in the Gowanus.”

At the time, there were few artists in the building, alongside a dwindling set of commercial tenants.

“There was a print shop that printed whatever you wanted, t-shirts and stuff,” he recalled. “Then there was a guy down in the basement making bottle caps and an old machine that was like Eraserhead.”

Cockrill took advantage of the low rent—he was paying $300 a month when he moved in—but there was a downside to the arrangement. “I got robbed so many times in my studio space, because this was a no-man’s land at that time,” he said. “The last time I got robbed, they didn’t take anything because there was nothing left to take. I had my paint and my canvases. They just came in, looked around, and left.”

The Old American Can Factory was also the home of artist Frank Shifreen’s studio, and about the time Cockrill moved in, Shifreen started hosting open-studio shows and networking with other artists in the building. Since many of the spaces were vacant, Shifreen had the idea to host a massive show in the un-rented areas of the building.

“The Monumental Show in 1981 was the first serious show in Brooklyn,” Cockrill said. “It was curated by Frank Shifreen and Michael Keane. It had like 150 artists. I got in because they saw some of my work and I lived here, but they called up artists they liked—Keith Haring, Komar and Melamid, Carl Andre.”

The show was a success, with thousands on hand for the opening on May 16. The crowds only got bigger when the landlord claimed Shifreen didn’t have permission to host the event. Besides establishing Brooklyn as a place to exhibit art, Cockrill saw the show signaling a change in style that would continue for decades.

“It was very interesting because you saw a shift in art in that show” he said. “There was a Carl Andre [work]; he found pieces of copper on site, bent them slightly, and made a row of them on the floor of the factory.”

“They were just walked on by people,” Cockrill recalled. “They didn’t function in any way that anybody even recognized as art. If you had put those in a clean white gallery, [they] would be like, ‘Ooh, look at these rusty copper plates in a row.’ But in a factory, they’re nothing. The Keith Haring was noticed. Everybody stood there looking at the Keith Haring because it was graphic. It was bold. It was fresh.”

Cockrill noted the same shift in the reaction to his own work in the show. “I did a little cartoon book with a person who lived [at the Old American Can Factory],” he said. “I also had large abstract paintings but they weren’t paid attention to. What was paid attention to was my cartoon book. There were people lining up to look at this cartoon book.”

“That’s when I realized, ‘That’s fresh. A big abstract painting is not that interesting right now.’” Cockrill decided to continue working with his collaborator on the cartoon book, changing his name to Judge Hughes for their work together.

One of the early Cockrill/Hughes collaborations was a wordless black-and-white graphic novel called The White Papers. Comprising the murders of JFK, Sharon Tate, and John Lennon, and rendered with explicitly sexual imagery, “that was the book that launched me,” Cockrill said.

The notoriety—and in some sense, the infamy—of The White Papers insured Cockrill’s inclusion in the mega-shows that characterized the Brooklyn art scene in the early 80s. With rosters of hundreds of participants and staged in alternative spaces instead of galleries, exhibitions like The Monument Redefined, the All-Fools Show and 1983’s Terminal New York in the expansive Brooklyn Army Terminal, helped establish the borough as a place for artists to show important work.

But most of the artists showing there weren’t from Brooklyn. “At that time, 1983, most of the artists I was aware of who were in that show were trucking out from Manhattan,” Cockrill recalled. “There were a few from Brooklyn. Williamsburg—it was the beginning of that by 1983, but there was no venue, besides a large factory, to show in Brooklyn.”

Though it took years for that to change, Cockrill’s sense is that most New York artists these days live and work in Brooklyn. “Artists wouldn’t step foot in Brooklyn, because it was almost like a status thing: ‘I don’t want to be in Brooklyn. I want to be a serious artist. Serious artists are in Manhattan.’” said Cockrill. “Then Williamsburg came along in the 90s. I joined a Williamsburg gallery, 31 Grand, run by Heather Stephens and Megan Bush. That was one of the best things that ever happened to me, joining 31 Grand.”

Part of the reason for the development of galleries in the borough was economic, reflecting Brooklyn’s more affordable rents. But Cockrill also sensed a different aesthetic in the developing Brooklyn spaces.

“Heather and Megan encouraged me to be me,” he said. Manhattan galleries “let me be me, but there was a little bit of fear like, ‘I can’t sell that. This work you are doing is gonna make my life hard.’”

“But in Brooklyn,” Cockrill found, “it was like: ‘Go for it!’ And they had the confidence in the work that they were able to sell it—like sold out. I never had sold out a show in New York before, till I got to Williamsburg—though I did sell out a show of my Baby Doll Clown Killers in LA. New York was resistant.”

That was a reflection, Cockrill said, of Brooklyn embracing the shift in taste that he first experienced at The Monumental Show. “Society had to change. The collector’s habits had to change,” he said. “I was using a lot of figuration in my work. Figuration was looked down on in the 70s and even in the 80s. The East Village showed figurative work but you could still run into dealers that thought figurative work was illustration. And on top of that, I was using sexually explicit imagery. That was also a taboo, and critics did not know how to wrap their brains around that. [They] pretty much attacked it.”

“But in the 90s,” said Cockrill, “women artists came along who were using very explicit sexual imagery in their work, and some males, but I liked what the women were doing. They were really kind of breaking that all down. And suddenly if they’re doing it, it’s sort of cool. My suggestive, aggressive work was beginning to gain acceptance.”

While the Brooklyn galleries were successful in documenting the shifting styles, Cockrill doesn’t think they’ve managed to achieve the cultural cachet that the most celebrated Manhattan galleries have.

“Bushwick has been an emerging venue for a while and I love democratic energy,” Cockrill said. “Some serious galleries have moved in, but I still feel, from what I’ve seen, most of the work is not ready for prime time. A lot of it is pretty good, even great, but clearly the Lower East Side has taken over as the new location. Even so, rents have gotten so high everywhere that the future seems up for grabs. Once something becomes too trendy, it’s going to be a problem. Artists and galleries are survivalists. They will go where the rents are cheaper.”

And just as rising rents in Brooklyn shape where artists can show, they also limit where they can work. “That’s a whole different thing,” said Cockrill. “Where you work is different from where you show. I’m really happy to have a studio in Brooklyn, and I know artists would love to have one here. I don’t know how younger artists can do it, because they have to get further and further out into undesirable areas. One other thing that has become great about Brooklyn are the art services. I can get my framing done in the Gowanus. I buy my art supplies around the corner at Artist and Craftsman and I had a recent series of bronze sculptures fabricated at the New York Art Foundry on the Gowanus—but they just lost their lease.”

Cockrill worries that skyrocketing real estate could cripple the vitality of Brooklyn arts in the next decade. It’s critical, he said, for artists to be working where they can see the work their peers are creating. “It’s super critical. I think artists need to go around and look at art. Don’t kid yourself, Facebook isn’t really the same.”

“When I was in my 20s, I didn’t know what art was,” he said. “And I would never have done The White Papers if I hadn’t met Judge Hughes, and I would not have done those cartoon paintings. I painted them, but I had a collaborator who was pushing me and made it okay to go there and challenge basically the entire art world at that time.”

“Not every artist is gonna help you,” Cockrill said. “Some will hold you back, and some are cautious. And you don’t want to talk to those artists when you’re young. You wanna talk to the one who breaks you down but finds an inner core in you and says, ‘You know what? That other stuff is bullshit.’”

Check out The Times exhibition on view at The FLAG Art Foundation, 545 West 25th Street in Chelsea, through Friday, August 11.