Local Lawmakers Slam City Property Tax Exemption Program, Saying It Has Lined Developers’ Pockets & Paved The Way For Gentrification

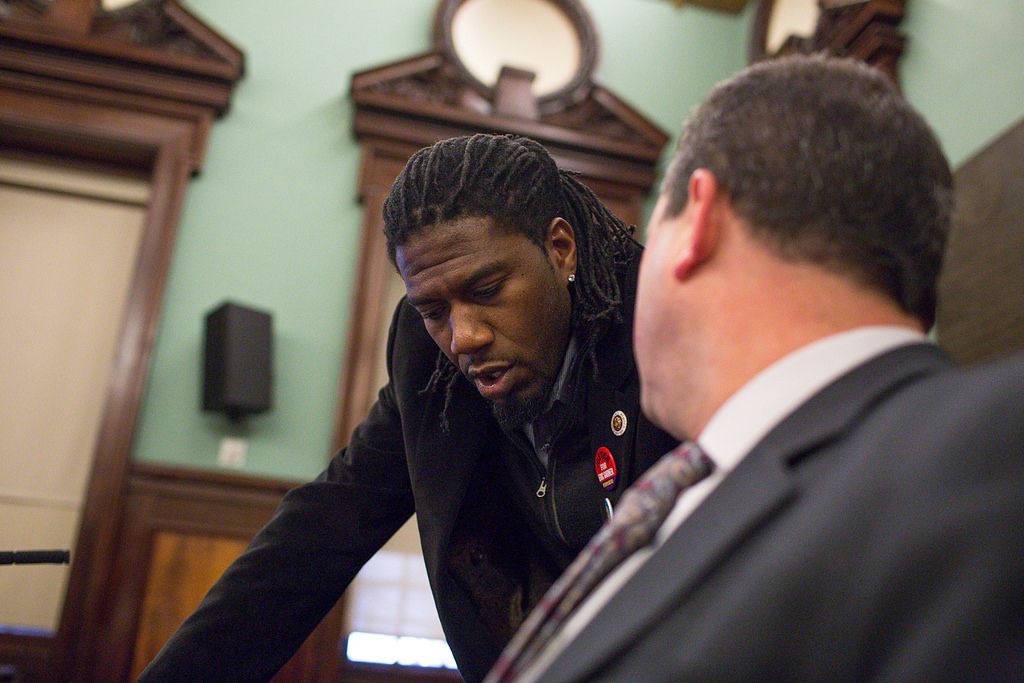

Local legislators slammed the city’s 421-a property tax exemption program at a hearing led by Councilman Jumaane Williams yesterday, calling it “all but a complete debacle” and saying the “broken code” has helped to line the pockets of large developers and paved the way for rapid gentrification across the city.

City officials are currently reviewing the 421-a program, which is set to expire on June 15, 2015 – meaning state legislators will have to vote on it in order for the program to continue. Therefore, lawmakers could allow it to sunset, revamp the program before renewing it, or give its current form the green light.

“It’s clear from today’s hearing that the 421-a tax exemption is all but a complete debacle when it comes to building affordable units,” Williams said in a press release of the program that was set up during the 1970s recession to incentivize development at a time when residents were fleeing the city. “… The only way it would be conceivable to continue this program is through an overhaul so thorough that it would make the current program unrecognizable. Which begs the question, should it even be renewed or should we just create a brand new incentive? I look forward to further discussion with the administration on this issue.”

As part of the program, developers were offered a tax abatement allowing them to pay real estate taxes on the assessed value of the land before construction for 10 to 25 years, depending on the project. At that time, affordable housing did not have to be built to receive the abatement.

However, buildings between 14th and 96th streets in Manhattan were excluded from this program, and developers were only able to get the 421-a tax abatement if they built affordable housing – including the 80/20 projects. (This, then, saved developers big bucks – often saving them millions in taxes with the 421-a program and allowing them to borrow money at incredibly low rates as part of the 80/20 program.)

At that time, developers didn’t have to build their promised affordable housing in the same building and could instead construct it elsewhere – often outside of Manhattan. This led to major criticism of the program, and it ultimately was revised so portions of Brooklyn and Queens also became part of this excluded zone – meaning the developer would have to build affordable housing if they wanted to land the 421-a tax abatement. Today, developers of almost all residential developments of five units or more can receive the 421-a tax abatement.

Critics have said 421-a has resulted in developers landing big tax breaks and not enough affordable housing being built. According to a new report from the Association for Neighborhood and Housing Development, the 421-a program in the fiscal year 2013 cost the city $1.1 billion in forgone tax revenue but resulted in only a little more than 13,000 affordable rental apartments.

This has led to vehement criticism from legislators like Williams, the newly inaugurated Assemblywoman Rodneyse Bichotte, Councilman Brad Lander, and Councilwman Laurie Cumbo, as well as from numerous affordable housing groups, including the Flatbush Tenant Coalition.

“There’s simply no justification for 421-a in its current form,” Lander said in a press release. “The one billion dollars in taxes the city gives up each year largely subsidizes the construction of exclusively market-rate units, in gentrifying neighborhoods, that would very likely be built anyway… Unfortunately, many of the decisions about whether to make those changes have to be made in Albany. If the program is not dramatically transformed through negotiations this spring, the Council should act to end the program.”

Manhattan Councilman Ydanis Rodríguez too slammed the program, saying in the same press release that, “for too long we have allowed the broken 421a tax code to rapidly gentrify communities across the city through on taxpayer dollars.”

“This program was developed during a time when the city was in decay and grown out of step with our city’s needs,” he continued. “Now, in an era of multi-billion dollar developments popping up throughout the city we must come together and instill substantive and extensive reforms law so that we can keep New York City affordable.”

Mayor Bill de Blasio’s affordable housing plan appears to advocates for 421-a to prevent what is known as “double dipping,” in which developers are able to qualify for benefits from a variety of affordable housing programs using the same residential units. According to the mayor’s plan, the program should be altered so the 421-a tax abatement is only available to a developer who agrees to produce more affordable housing than would otherwise be required.

During yesterday’s hearing, however, Capital New York reported that the de Blasio administration’s top housing official would not give her opinion on the 421-a program and “would only say that the administration is analyzing the program including looking for ways to make it more efficient.”