Leo Lee: Serving Our Community For 66 Years, From The Kitchen Of New Toysun To The Aisles Of Discount Plus

My niece is graduating high school. I want to send a card. The kind that you lick to seal, the kind that can hold a check from a proud Auntie.

I pop in to see Leo Lee at Discount Plus. Leo has the best cards. I can’t remember him ever not being there, standing behind the counter, seven days a week, in a red vest with a name tag that reads: “Leo, May I help you?” Sorta pointless. Everyone knows his name. Nobody says, “I need paper towels; let’s go to Discount Plus.” They say: “Let’s go to Leo’s.”

As usual, he’s there, stationed behind register one, counting a river of silver: nickels, dimes, quarters. William, my seven-year-old, would be in heaven. Clearly, counting coins and calculating totals has been good for mind and body. Leo stands straight, smiling, in robust health, his mind as sharp as the disposable razors on display behind him.

Leo’s son Gregory, at register two, is all-Brooklyn, about my age (OK, probably younger.) Strong from hefting boxes of bottled water, he skips the vest and sports an AC/DC T-shirt instead. Observing them side by side, Greg is proof that great smiles can be passed down. Customer service, on the other hand, is a learned trait, one learned here, at 957 Coney Island Avenue.

I’m looking around, waiting for Leo to finish counting his Yangtze river of loose change before I start shooting questions. Leo’s has four wide aisles: housewares, health and beauty, school supplies, greeting cards.

By the entrance, a glass case sparkles with cologne, classic and contemporary. I see my mother’s summer scent, White Linen, and one that the woman whose children I babysat for in the ’80s wore. After tucking those kiddos in bed, I’d sneak a spritz of Charlie from her vanity table. She must have known. I reeked.

The men insist we can talk, even as they ring up customers. So we start, back and forth, over the counter. I’m mesmerized by three goldfish chasing tails through the roots of a water lily, in a homemade aquarium/planter, fashioned from what looks like a Costco pretzel jar.

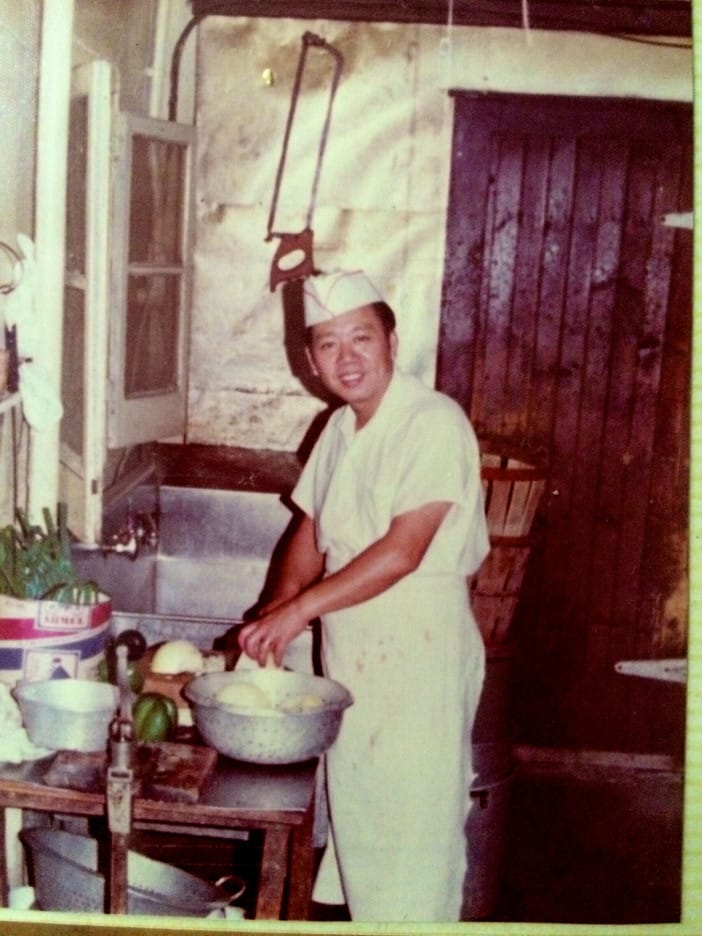

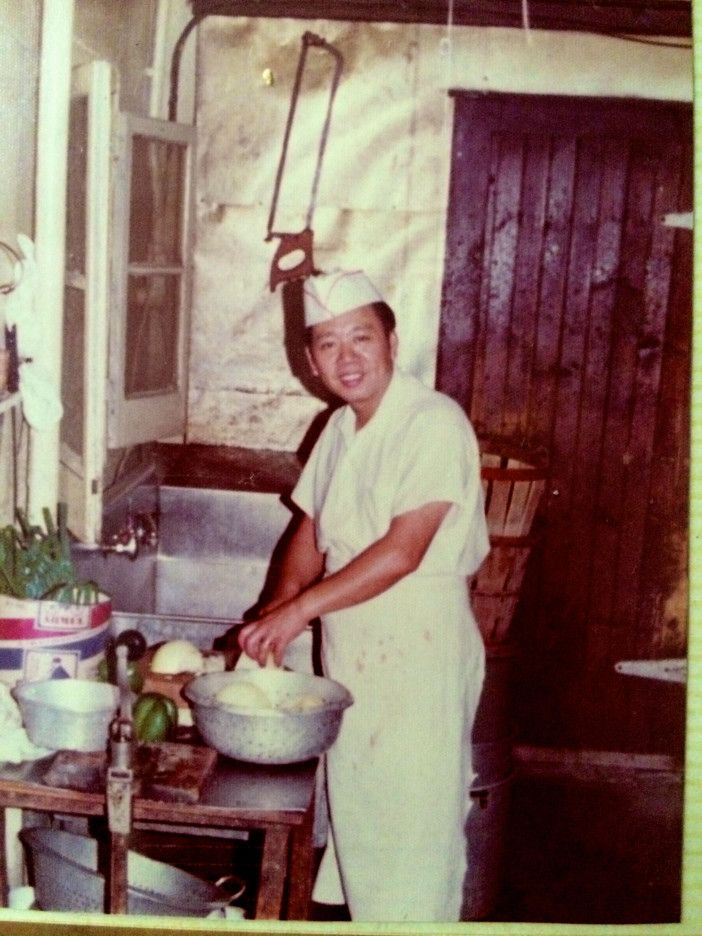

At 16, Leo Lee came from the village of Toysun, China, in the Pearl River Delta, 140 kilometers west of Hong Kong. But his father had arrived years earlier. In fact, Leo’s great-grandfather settled in Massachusetts in the 1880s and found work in a hand laundry.

“My father came here when he was 13,” Leo says. “He was living in Boston. He was a waiter. In World War II they drafted him. After the war, with the GI Bill, he brought me over. My mother came later. I was with him. I was 16. And then my father started the restaurant in New York, because he was already in that business.”

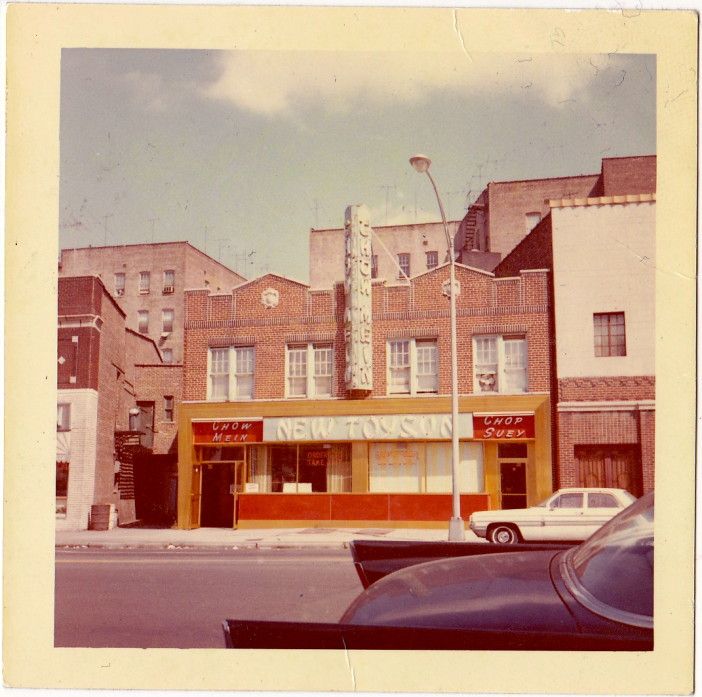

New Toysun, a Cantonese restaurant, named for the family’s hometown, opened in the space where Discount Plus is now in 1949. Leo Junior and Senior lived in the apartment upstairs.

“It was a sit down Chinese restaurant,” Gregory points out. “We also had take out from the start.”

Greg leads me to the north wall, rolls away a helium tank, and shows me the original phone used to take orders. He lifts the receiver and holds it to my ear. Whaddya know? A dial tone.

“Isn’t that something? It still works!” he remarks. “The take-out counter was here, along this wall,” where today, mylar balloons await inflation: “Welcome Home” and “Birthday King.” I wonder how many orders for shrimp lo mein were taken on that wall phone?

“I was a youngster going to school,” says Leo. “Erasmus High, and after school I helped out.”

“What was it like for you, as a child coming here in the ’50s from China. You were one of the only Chinese kids in this neighborhood. Did you make friends in high school?”

“Yes,” Leo answers.

“Did you speak English?”

“Not much.”

“How was it learning English at 16?”

“Not easy,” he says with a broad smile. “I went to a special school for two years, a public school. It was in the Bronx. PS 27. They had a class for kids who were older than regular elementary kids, 14, 15, 16, and they all came from different countries. We had kids come from Germany, Hungary, Italian, Puerto Rican. Me, I was the only Chinese. We mainly learned English.”

“And then you came to Erasmus, when your English was a little better?”

“Right. Not perfect, but a little better.”

It sounds pretty perfect now.

“So how were the kids in the neighborhood. Were there any gangs? Was there any fighting between the Irish and the… whoever?” Irish is what comes to mind, fair or not, because in East Harlem, during the Great Depression, Irish boys liked to beat up on Greek boys, or so said my Grandpa Theodore.

“No, in those years they were more peaceful. Nobody carried a knife. Nobody carried a gun. You boxed. You hit each other with the fists.” Leo laughs. “It was different.”

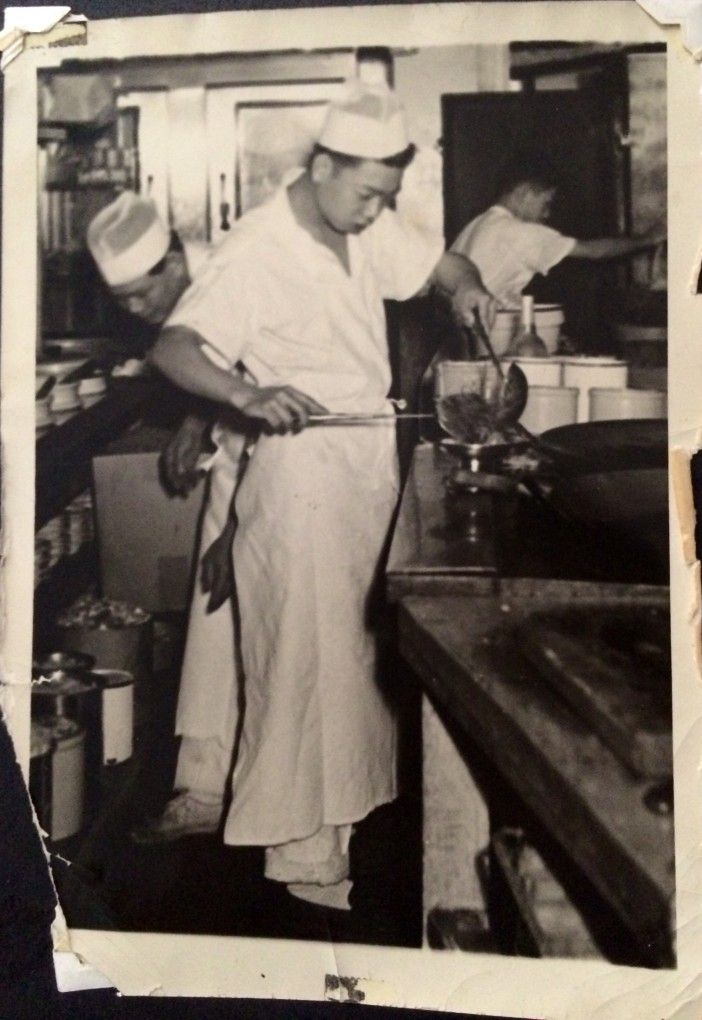

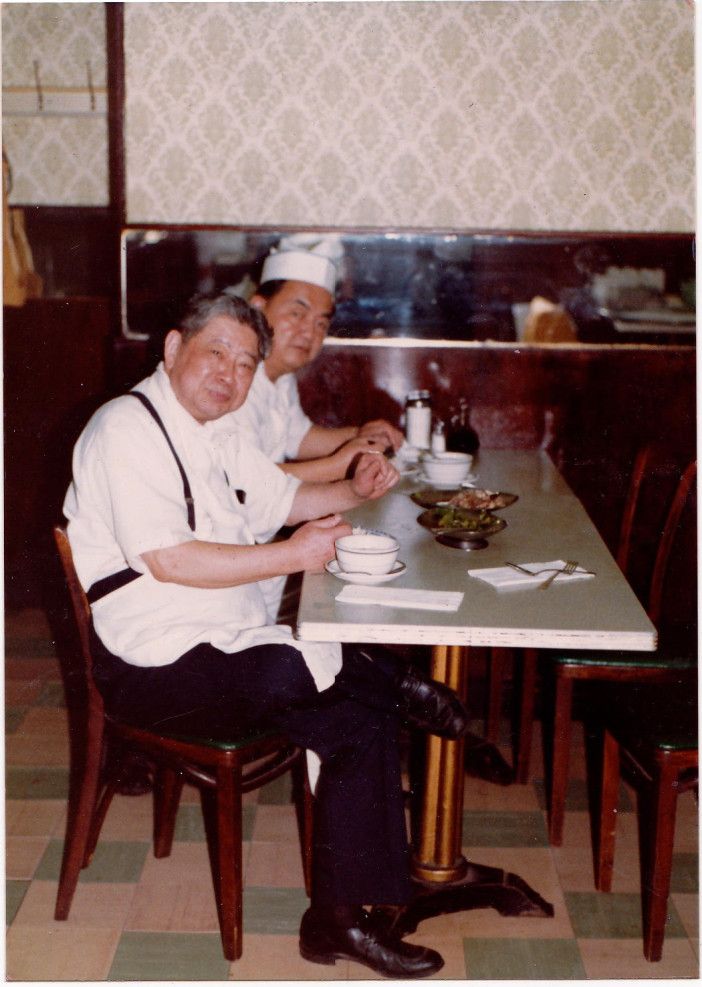

“We had about four or five waiters. In the kitchen, we had about four or five people too. Plus my father and me.”

“Were there any special dishes that your father cooked that were from Toysun?”

“Mostly all the dishes were from Toysun, except they added some dishes, like chow mein. They didn’t have that in China back then.” Enter Chinese-American cuisine.

“Where does chow mein come from?” I’ve always wanted to know.

Leo shrugs, “I have no idea. It started here.”

Greg explains: “Chow mein, lo mein, it’s all varieties of stuff they made in China, it’s a little different over there though.”

Right. That’s an understatement. I’m guessing Cleveland lo mein is as close to Toysun home cooking as Spaghettios are to Nana’s lasagne bolognese.

“What about chop suey?” I belabor the point. “That was on all the old menus too. Did you make chop suey?”

“Yea,” Leo laughs, “Now they call it mixed vegetables.”

New Toysun, a real chop suey joint. I’m tasting crunchy cabbage, celery, bean sprouts, and scrambled eggs. Yum.

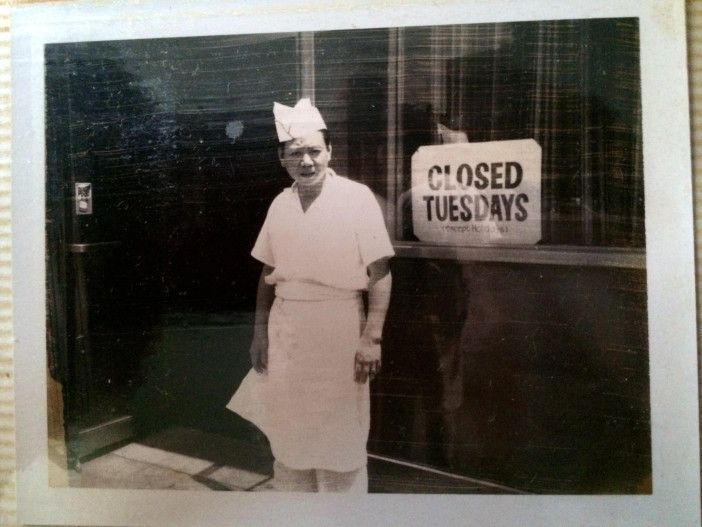

“How many days were you open?”

“Seven days,” says Leo.

“No you weren’t, you were closed on Tuesdays,” Greg corrects.

“At the end. In the beginning we were open seven days.”

“So the restaurant ran from 1949 until…? When did it close, about?”

“I don’t remember…” says Leo.

“1990,” Greg helps out.

“Wow, And it was a sit-down restaurant that whole time?” I’m thinking of Nice China Town at 1411 Foster. I’m hooked on their mock chicken broccoli, but the three uncomfortable booths are only for resting your fanny while waiting for your order to come up.

“Sit down and party room,” Greg adds. “On weekends it would get busy. Friday, Saturday, Sunday, you’d have a line out the door, so you had to open up the side party room to handle the crowd. So basically, you would have four waiters in that party room, and how many in here, Dad, four?”

“No, three.”

“So we’d have seven waiters on the weekend, just so we could handle the crowd,” says Greg.

“We could hold about 200 people…” Leo reminisces.

“Where did all the waiters and cooks live?” I ask.

“Most of them lived in Manhattan. Chinatown. Canal Street. They’d take the train and they’d get here,” replies Leo.

“In the ‘50s there was a movie theater next door called The Leader,” Greg recalls of the space at 947 Coney Island Avenue. “And they would close at like, one o’clock in the morning. You’d think that would be dangerous today, but because the movie let out, there were a lot of people on the street after the movies, who wanted to eat.”

“Was the place ever robbed?”

“No,” says Leo.

“Good. Was there a gun behind the counter?”

“No.”

“In those years, there were no gates. The door, you could kick it in. The whole city, even in Harlem, everybody had glass doors, and you could open them without clippers. And at night, nothing happened. The store owner used to go out into the street talking to the neighbor. The summer is warm and, and he’d leave the door wide open,” Leo shrugs.

“No air conditioning,” I observe.

“We had air conditioning,” Leo corrects me.

“Wow, air-cooled, from the start!” Not bad.

“Yeah, but explain it, Dad; it’s different,” says Greg.

“In Brooklyn there’s water underground, and it’s cold, so what they did is they had a pump, and they would pump up the cold water from the ground. It would go through a coil, cool the coil, and a fan would blow through it, and blow out cold air. Water-cooled!” Leo boasts gently, his nametag imperceptibly rising on his vest.

“We still use it. It’s in the back as our second unit, but it doesn’t work as cold as this new system, but still, it’s 50-degree water underneath the ground.” Greg seems happy to have the backup unit to carry them through July and August.

“That sounds so environmentally friendly too,” I add.

“So we had our own well dug back then.They didn’t want you to use city water to do that. Today that would be very expensive, to have your own well dug. Then they’d have to test that water and everything.”

“Next door, the movie theater had the same system too,” Leo points out.

“What was the name of that theater again?” I forget.

“The Leader. L-e-a-d-e-r. Like the Leader of the Pack,” says Greg. “The Leader Theater, then the Leader Lanes, the bowling alley, after that. Here’s a picture of the corner from 1949. So that’s the movie theater and if you can look really close, on the marquee, it says something about being cooled. They didn’t even know what the word air conditioning was. What’s it say here Dad?”

“Air conditioned?” guesses Leo.

“No, Dad, I just said, there was no such thing as air conditioning. How could they use the word air conditioning?”

“Air-cooled maybe?” Leo

“What happened to the bowling alley?” I ask.

“The pharmacy took half of it,” Greg explained. “Not all of it.”

I’m picturing a wall of glass bottles, aspirin and cough syrup, backing up to six lanes of rolling thunder, balls kissing pins, all night long. How’d that work out I wonder, a pharmacy sharing a common wall with a bowling alley?

Back to the restaurant.

“Wait, so how late were you feeding people?”

“At least midnight, and on weekends even later, one or two, ” says Leo.

“Can you imagine that?” Greg exclaims.

No I can’t. I’m trying to calculate what time Leo’s head hit it’s pillow on weekends. Had to be 3am. No wonder he lived upstairs. (Still does. Owns the building now.) New Toysun served up midnight snacks, nightly, for 41 years straight. Holy cannoli! (or better, holy egg roll-y!)

“I never experienced that,” Greg sighs. “But they used to tell me…”

The Brooklyn that never slept. Today, at midnight, you can pick up a gallon of milk or a Mexican mango at the grocery catty-corner to Leo’s, but really, Coney Island Avenue at Newkirk is dead after the Mr. Softee truck pulls away from the curb around eight.

“What happened to the restaurant in the ‘60s?” I ask, “When did your mother come?”

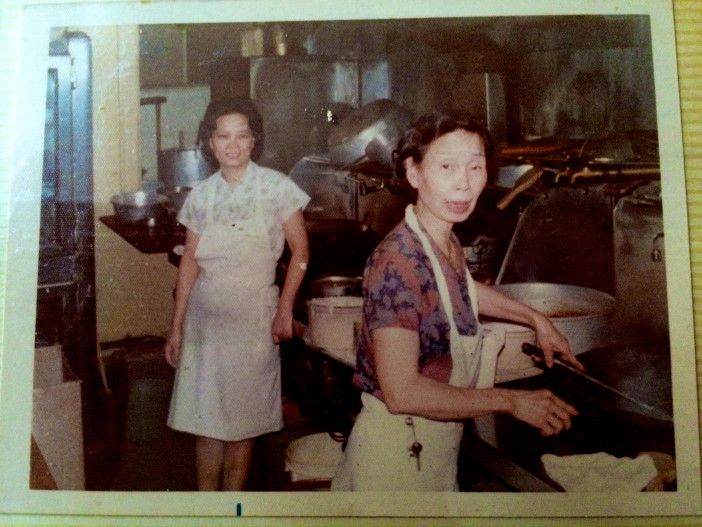

“My mother came in the mid-’50s,” said Leo.

“..and she jumped right in?”

“Yeah. She was in the kitchen. And then my sisters and my daughter, they would help out with the take-out and the cash register, after school.”

Wait, I’m not up to your daughter yet Leo. I want to hear about your romance.

“What is your wife’s name Leo, and how did you meet her?”

“Betty. I was on vacation in Hong Kong. Somebody introduced us, and on Monday we got married.”

“Wait, wait, wait… Leo, how many days did you know her before you got married?”

He smiles slyly, “I would say… less than two months. She was a high school student. I was about 24.”

“Crazy huh?” Greg laughs. “I waited eight years to propose, and I thought that was too soon.” What a difference a generation makes.

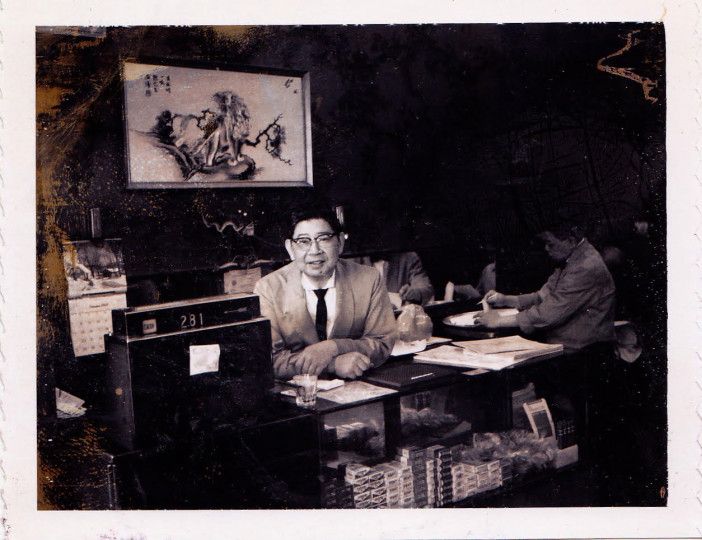

“Who controlled the cash register?”

“My father, and the waiters helped out.”

That’s trust. I can’t really see restaurant owners letting waiters ring up cash-paying customers today. I couldn’t get anywhere near the register of the Times Square honky-tonk where I waited tables back in the Madonna era…

OK, I want to draw all the branches of the family tree here.

“So Leo, how many children did you and Betty have?”

“Three. Paula, Andrew, then Gregory; he’s the youngest.”

“And how many children do you have Greg?”

“I have two children. Nicholas and Melissa.”

I live around the corner from an elderly woman. She’s over 90, but with the help of an aide, she still gets out into her garden most mornings. From our living room window, which overlooks her backyard, my son William and I have watched her tending squash (I think it’s squash) the length of my arm. I’ve harbored a foggy notion that Mrs. Hom is somehow connected to this story, and I want to clear the haze.

“And the house on Foster…”

“That’s Dad’s aunt,” Greg clarifies. “Her husband also worked here, Dad’s Uncle Tom.”

Tom Hom.

“They both worked here,” Leo corrects. They came over in the late ’50s, maybe ‘57.”

“Your aunt’s family bought that house on Foster in the ‘50s?”

“They were living above the restaurant for a couple of years, but then they needed more room. They had three kids, so they bought that house. A few years later.” Leo explains. “Also my Uncle Tom, my mother’s brother, he was an ex-GI too. That’s why, after the war, with the GI Bill, they brought the family over.”

Dang. Cheap home mortgages and cash for college tuition, and now apparently this — help to haul immigrant families stateside — that Servicemen’s Readjustment Act of 1944 had to be the best economic — and moral — piece of legislation signed into law by any politician of the 20th century. Way to go FDR.

“You know what?” says Greg. “I gotta give you a book. A writer named Harvey Wang wrote a book about the restaurant. He talked about how my grandfather said that the only way you get out of working in the restaurant, is when you get married, cause when his daughter got married she moved to Connecticut.”

“I love that. Let’s get back to the food.”

“What was the most popular dish on the menu?”

“I think chow mein probably,” Greg suggests.

“Chow mein, barbecue spare ribs, and shrimp lobster sauce,” Leo states. End of story.

“We had specialty stuff, like Worshiu Chicken, that you don’t see around anymore,” offers Greg.

“How do spell that?” I ask.

Greg laughs.

“How do you spell Worshiu Chicken?” he turns, and repeats to his father.

“Who knows?” I ask.

“Do you know dad?”

He did.

“W-o-r-s-h-i-u. Chicken. It’s breaded chicken with special vegetable sauce on top.” Sick. No really, hou sik. That means delicious in Cantonese.

“And is that specialty from your family’s part of China?”

“Yeah, with a dark gravy…” Greg describes it, “with all kinds of mixed vegetables: Chinese mushrooms, regular mushrooms, celery, bamboo shoots and other vegetables, in this sauce, poured over the fried chicken breast.” Slobber.

Noon approaches. Never mind that I’m facing a wall of Lotto tickets, standing under a strip of Chapsticks in assorted flavors, and surrounded by cases of bottled water. In my head, I’m pulling chopsticks out of their paper sleeve and rubbing them together in anticipation of the lunch special: Worshiu Chicken.

“And what was famous in our restaurant, and in Chinese restaurants in the ‘50s, was the family style, where you picked two items from column A, two items from column B. It was dependent on how many members you had in your party. You had dinner for two, three, four, five, six. Column B had the more expensive items…”

Leo takes over: “Say dinner for six, you get three from column A and three from column B.”

Greg jumps back in: “And each meal included…”

And now, so excited, they both talk together: “Dessert, tea, soup and egg rolls.”

“What were the soups?” I ask.

“Wonton or egg drop.They got the choice,” says Leo.

“And what was for dessert?”

“Ice cream, Jell-O, cookies, sliced pineapple.” Again that lovely smile.

“Nice!” That’s refreshing, a dessert menu that doesn’t offer a flourless, dark chocolate wedge with a squirt of syrup.

“I gotta get you that menu,” Greg jots a note to self. “Dinner for six was like what Dad? Twenty dollars?”

We all laugh.

Arnold, a longtime resident of 570 Westminster around the corner, approaches the counter with a pair of slippers, lined in rubber fingers that massage the instep. Like Leo, everyone knows Arnold, and his shedding golden retriever. He jumps into the conversation: “Everything was excellent, excellent, no matter what you ordered. You hear me? And his ice cream was even better!”

“His ice cream was good?” I ask.

“I used to take three quarts a week! Cherry pistachio,” Arnold sighs for effect.

“They sold ice cream, to go?”

“Well, regulars like Arnold would start doing that,” explains Greg. “We really didn’t publicize it.”

I’m imagining double scoops cherry pistachio, dished up in restaurant china dessert bowls, red and green, Merry Christmas delicious!

“Ahhhhh… Are you kiddin’?” exclaims Arnold. “Lemme tell you something,” and he’s staring me down now. “Anything you ate here, in this restaurant, was excellent!” I glance at Leo. “Don’t look at him!” commands Arnold. “I’m telling you the truth! They also had another good restaurant across the street, an Italian Restaurant, Vesuvius.”

“Friends of ours,” says Greg.

“That was excellent too,” observes Arnold. “Lemme tell you, they had a few good places, at that time. Nowadays you’re getting all crap wherever you go, and they’re charging you big money. For nothing! We agree?”

“We agree,” I reply, “I cook at home a lot.”

“There you go!” And Arnold’s out the door.

I love Arnold. Back to the New Toysun.

“What was the decor like?” I ask.

“The wallpaper was green…” Leo starts.

“And the booths were green…” Greg continues. “The wallpaper had a green and white flower motif, I think.”

“And plain wood tables?” I suggest.

“No! No!” I’m shot down. “Tablecloths! ALL tablecloths!” Greg insists.

“We had Formica tables, but we put the tablecloths on top,” Leo points out.

“And cloth napkins, not paper!” Greg adds.

“And who was your clientele? Chinese-American?” I ask.

“No. Mostly white. 99 percent,” Leo replies.

“And what was white, here in this neighborhood, back then?”

“Jewish, Irish, and Italian, 95%” says Greg.

“Your Jewish customers didn’t keep kosher?” I ask.

“Right, exactly. Non-kosher,” confirms Greg.

“Did you ever have Chinese families come eat?”

“Very rarely,” says Greg.

“Did you have a cocktail bar?” I am picturing Singapore slings with paper umbrellas, propped by multiple maraschinos.

“No, we didn’t have a liquor license,” says Greg. “But there were customers who would bring their own bottles of wine.”

“BYOB even then,” I remarked.

“Yea,” Greg laughs. “BYOB. Even back then. Isn’t that amazing?”

“Where did you shop to buy the vegetables and the food for the restaurant?” I ask.

“They delivered,” says Leo. “Wholesale. On the phone.” On that wall phone. “I’d say: ‘I need two crates of celery, two bags of onions.’ And they’d deliver. Same goes with the meat.” Leo smiles, just that easy. It was a business. The Chinese restaurant business. But it was more than that too.

“What about your family’s traditions? Being the only Chinese-American family in this neighborhood, running a restaurant seven days a week, did you ever get into Chinatown to celebrate the New Year, or to a temple?”

“Mostly we stayed as it is. We didn’t go anywhere,” says Leo.

Of course, how could they go, when customers showed up on their doorstep daily for spare ribs and cherry pistachio?

“Our holidays in China weren’t allowed to be religious,” Greg explains. “Our holidays were based on the moon. The moon festival, and Chinese New Year of course, and then there are all these holidays based on food, that’s how I always remember it. We still do it. Make the special foods for the holidays.”

Moon-inspired holiday meals. Mmm… mmm…

“Like there’s a holiday that just passed now. Where you make the umm… I don’t know what you call it… It’s like a tamale…” Greg tries to describe it.

A Chinese tamale? Please, do continue…

“Rice wrapped up in like umm…”

“Bamboo leaves,” Leo interjects.

“Bamboo leaves, with meat and stuff, and then you steam it. What’s that holiday called, do you know?”

“That’s in May,” says Leo.

He doesn’t know. It’s OK.

“Right. And you made it recently,” adds Greg.

“Yes. Then there’s the one with the moon cake in August,” adds Leo.

Holiday names and observances seem beside the point. It’s all about the food.

“Right. I don’t really know the history of those holidays, but I remember growing up, always at certain times of year, certain foods, and we continue to do that.” I’m more than satisfied with Greg’s explanation. I just hope they remember to save me a Chinese tamale when the moon cycles around to the right month next year.

“So on these holidays you’d put those dishes on the menu, as specials?”

“Naah…” they both jump to answer.

“Oh, just for the family,” I stand corrected. “But you’d eat those special foods here, at the restaurant. I have to say, Leo, as an American walking into a Chinese restaurant, sometimes I see them serving food to their own family, and I say: ‘That looks good, I wonder if that’s on the menu?’ And it’s not always on the menu.”

They’re laughing (with me? at me? whatever).

“Well that happened with us,” says Greg. “Because in that party room, during lunch time when the cooks and everybody ate, it was more traditional stuff, and some customers would say, ‘We’d like to see that on the menu.’ Today you’d see more of it because all the restaurants in Chinatown, on 8th Avenue, cook like that now, and not like the traditional American-Chinese food. But most of their customers in those 8th Avenue restaurants are Asian. You do see some other people beside Asian though.”

“So what would your waiters eat on lunch break? Congee?’’ I ask.

“Yes, they would make congee for the workers.”

Gotta admit, I can’t picture my Scottish-American neighbor, Don Loggins, and his family, who dined often at New Toysun, turning down two from column A and three from column B, for five steaming bowls of congee. Leo Sr. knew what he was doing with his menu.

I’m now just noticing the music, piped in through speakers overhanging the registers. I’m yanked from the ‘50s to the present. Okay maybe only to the ‘80s synthpop era: “She’s a maniac, maniac on the floor, and she’s dancing like she’s never danced before…” Flashdance, I983. I can’t name one 99-cent store in the area which offers music to shop by. Only the Rite Aid or Duane Reade, and Leo’s is closer to one of these than a 99-cent store. But Leo’s is oh so much better than a chain…

“What else do you want me to know, about your experience, your restaurant, anything?” I ask.

“All I can tell you is we worked hard and we made a living,” Leo delivers this as if he’s said it many times before, as if he’s speaking for his entire family, going back, for generations.

“You made a good living,” I add. A Horatio Alger story, set on Coney Island Avenue.

“And he always says he’s been serving the community, from this location, for 66 years. 40 in the restaurant, and now 26 in this discount store,” Greg adds.

“Were you one of the first discount stores in this area?” I ask.

“Yes,” Leo answers.

“It’s a good location — next to the school,” I point out. PS 217 has 1,400 kids — that need pencils.

“Greg, after the restaurant closed, did your mother work in the store or was she pretty much done?”

“She was pretty much done. She would sit in the back and do certain things.”

“But you’ve done all the ordering…” I say.

“Yeah, I do pretty much all the ordering.”

“What’s your top-selling item in this store? You’re gonna tell me it’s Lotto tickets, no? Or cigarettes.”

“School supplies and beverages,” Greg doesn’t have to stop to think. “And paper goods. Everybody needs paper towels and toilet paper.”

It’s true.

“And lemme tell you, you’re the only place in the area to get a card. I get my greeting cards here.” Okay, there’s the Rite Aid, three blocks east, on Newkirk at Marlborough, but you’re hard put to match a card to its envelope there.

“And we give 50 percent off,” Greg brags.

“Exactly, you can’t beat it!” I may be the only tree-hugger who hasn’t taken well to electronic greeting cards.

“What about the language? You obviously still speak Cantonese, Leo. What about you Greg?”

“I speak Cantonese with my parents. My wife is also Asian, but we’re Americanized, so we don’t really speak Chinese to each other, so my kids only know bits and pieces. I kind of regret that. My son is taking Mandarin now — which is totally different from Cantonese — but he wishes that we had spoken more Cantonese in the house.”

“Well, it’s not too late…”

“Right, Well, he’s picked up a lot in the last year, but it’s much easier when you’re just growing up with it. I tell my mom that she should have spoken more Chinese to them, but she liked learning English from them.”

“That’s how it goes,” I observe. The American experience. Fuggedaboutit!

“Like my son tells me, his friends that are more, what’s the term? FOB, ‘fresh off the boat,’ whose parents haven’t been here long. They speak strictly Chinese in the house, so even though his friends have been in this country a while, they are fluent in Chinese.

“But you know, when I grew up, I went to 10 bar mitzvahs. All my friends were Jewish and Italian and Irish. That’s who lived here.”

God bless America. Really. I mean it.

One last question:

“What’s on your bucket list Leo? Do you know that expression? What do you want to do before you…” I flex my foot to demonstrate: “kick the bucket?” He still doesn’t get it. “Before you die Leo,” Not classy, but I want to know. “Is there something you want to do? Anyone you want to see?”

“I don’t have anything in mind,” he reflects.

I’m a little surprised. I wasn’t expecting a Perillo tour of China’s Great Wall, but how about Vegas or Niagara Falls? What about a family meal with all the third cousins at the best dim sum off Canal Street?

“So you don’t want to retire?”

“No,” he says.

“You don’t want to sit home and…”

“No,” he cuts me off. “I enjoy this.”

And why not? He gets to work, side by side, with his grown son (and sometimes even his grandson), who so expertly stocks the store with items people need, at affordable prices. He gets to reminisce with old timers like Arnold. He’s gets to stay useful, connected. Those human desires never retire.

As I slide five quarters across the counter for my niece’s graduation card, I think of the closing scene in A Christmas Story, that holiday flick from 1983, same year as Flashdance. When the hounds scarf the yuletide turkey, Ralphie and family wind up downtown, celebrating Christmas at the local Chinese restaurant. The waiters circle around the table (yes, covered in cloth) present roast Peking duck (head still intact,) and belt “Deck the Halls!” There’s great heart in that scene, and there’s great heart here, at 957 Coney Island Avenue, always has been, whether they’re selling egg foo young back then or triple A batteries today. Triple happiness.

I leave, warmed by this family’s story, and really hungry. I return the very next day with my own 11-year-old. He has his first summer job as mommy’s helper to his piano teacher, and he wants to spend his earnings on a treat for his five-year-old charge. He heads for Leo’s four-tiered candy carousel. One buck buys two Tic-Tacs or two packs of Trident Gum, or kid brother William’s favorite: a baggie of Hershey’s Kisses.

“This is the best discount store,” raves Theodore, trying to choose between mixed fruit or mango Tic-Tacs. “They have really good deals!” He eyeballs the bottled water, already a comparison shopper. “You can get five eight-ounce bottles of Kirkland water for one dollar, or four 12-ounce bottles, or three 12-ounce bottles of the Poland Spring!” He’s amazed, how can they offer such good prices?

Beats me. That’s Leo, serving the community for 66 years, and still going strong!