Gravesend: Southern Brooklyn’s Historic Capital

Ever wondered about those big ol’ houses you pass on your way to the train station? Curious about the famed Sheepshead Bay race tracks? Ever wanted to know how our neighborhood, so unique from the rest of Brooklyn and New York City, came to be the way it is? Joseph Ditta did, too. His curiosity was sparked by strolls through the Gravesend Cemetery and the names dating back to 1650, which also dotted the areas streetnames. Ditta began compiling photographs, postcards, lantern slides, stereoscopic views, engravings, paintings, textiles, artifacts, manuscripts, books, and maps to piece together the early days of the Village of Gravesend, which includes Sheepshead Bay and many of the surrounding neighborhoods.

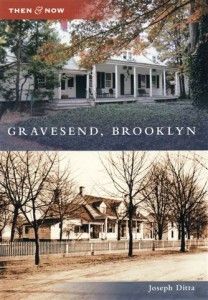

Now 42 years old, Ditta has turned his research into a book titled Gravesend, Brooklyn. He chronicles Gravesend’s rise from a farming town established in 1645, through its annexation by Brooklyn in 1894, and its present years. He hopes his work will “give the busy residents of Gravesend, Brooklyn, reason to pause and ponder the historical significance of sites they pass each day without truly seeing.” He took a moment from his unending research into Southern Brooklyn’s history to talk to Sheepshead Bites about the past, the present, and the future of Sheepshead Bay.

What is so interesting about Southern Brooklyn history?

Few people realize that Southern Brooklyn has only been part of Brooklyn for little over a century. What is now Brooklyn, or Kings County, was originally divided into six self-governing towns founded in the 17th century on the southwestern tip of Long Island. Five of the towns were settled largely by Dutch immigrants; these came to be called Bushwick, Flatbush, Flatlands, New Utrecht, and Brooklyn. The sixth and southernmost town, Gravesend, was founded by a band of English religious dissenters who fled intolerant Massachusetts for the more hospitable climate of New Netherland (rechristened New York once the British took over in 1664). Eventually, the town of Brooklyn became an incorporated city, and between 1854 and 1896, absorbed each of its neighbors (Gravesend was annexed in 1894) until its borders equaled Kings County’s. Brooklyn, in turn, became a borough of Greater New York City in 1898. It is that history on the cusp—the transition of Gravesend from Long Island farming town to an urban neighborhood in the city (now borough) of Brooklyn—that fascinates me. There are surviving traces of that transition that have defied development, and I have spent more time looking for them than I care to say!

Why did you write a book about Gravesend, and not a much cooler neighborhood like, oh, say, Sheepshead Bay?

Ah, but Sheepshead Bay is in Gravesend! The historic boundaries of the town of Gravesend were much larger than the current neighborhood of that name (which is roughly contiguous with ZIP code 11223). My book focuses on as many localities as those borders once encompassed, to the extent that I could cover them in Arcadia Publishing’s 95-page format. Gravesend included all or parts of the Southern Brooklyn neighborhoods of Bensonhurst, Ulmer Park, Brighton Beach, Manhattan Beach, Gerritsen Beach, Plum(b) Beach, Marine Park, Madison, Midwood, Homecrest, and Sheepshead Bay. Even in my limited space, I present a number of sites in Sheepshead Bay, such as the home of John Y. McKane, Gravesend’s corrupt town supervisor, which stood at the northeast corner of Voorhies and Bedford Avenues; the Ocean Avenue Bridge; the mansions of Millionaires’ Row along Emmons Avenue; and the makeshift tents of Plum(b) Beach.

What’s the most fascinating tidbit you came across while researching your book, Gravesend, Brooklyn?

That’s a tough one, since I am obsessed by the most obscure details of Gravesend history! I had shifting favorites as I worked on each caption in turn, and even now, published book in hand, I am hard pressed to say which most fascinates me. A strong candidate is the fence surrounding the Homecrest Presbyterian Church at 1413 Avenue T, depicted on page 48. The church was built in 1901 (with a 1922 addition), but its fence, salvaged in 1929 from the front yards of a demolished row of houses on West 23rd Street in Chelsea, Manhattan, dates from 1845! If you’re in the area, be sure to have a look at this remarkable example of early adaptive reuse.

What do Sheepshead residents have to be proud of in their ‘hood’s history?

That waterfront, hands down! Where else in New York City can you find a similar, sheltered inlet complete with fishing fleet? Originally called “The Cove,” the Village of Sheepshead Bay actually developed quicker than many other areas in the Town of Gravesend, due, in large part, to the presence of the world-class Coney Island Jockey Club (a.k.a. the Sheepshead Bay Racetrack), which brought wealth, hotels, and railroads to what had been a sleepy backwater. The heyday of Sheepshead Bay is long past, perhaps, but I hope my book will help to perpetuate the memory of what is lost so current residents can find grounding in these shifting times.

The past century has seen a lot of change in Southern Brooklyn. What have been some constants throughout that change?

I’ve lived in Gravesend all my life—not terribly long at 42 years—but sometimes even I can’t recognize the place. If I have trouble, imagine what shock would be in store for someone who lived here centuries ago, were they suddenly brought back. One thing they’d recognize, despite the elevated F train rumbling through it, is the layout of the Gravesend village square, which survives virtually unchanged from the 1640s, although engulfed by the 19th-century street grid (here’s a map pinpointing the site). The intersection of McDonald Avenue and Gravesend Neck Road is ringed by Village Road North, Village Road East, Village Road South, and Van Sicklen Street. This four-block pattern is among the earliest examples of town planning in North America.

The area has probably never changed as much as it has than since the fall of the USSR, when waves of Eastern Europeans arrived, and we saw a strong U.S. economy and a housing boom changing the landscape from one- and two-story homes to condos and low-rises. Can you give us more insight into these changes?

Even the venerable Gravesend village square was affected by the unfortunate boom! In 2003, several older, frame homes on oversized lots on Village Road North were demolished for towering brick and steel monstrosities that are completely out-of-scale with their surroundings. Do the occupants of these buildings have any idea of the age of the street on which they live? Do they care? That, I think, is the crux of this “knock-’em-down / build-’em-up” crisis: no one seems to care; not the sellers of the old homes, who’ve made a quick buck; nor the buyers of the properties, who’ve made a killing; nor the residents of their shiny new condos, who (while I’m sure they’re hardworking people going about their lives) have no idea of the history they’ve unwittingly usurped. It is a relief that the fever to build has broken. My book takes stock of what survives, at least in part.

Drawing from your knowledge of the area’s history, what do you think the area will be like in a decade? In a quarter century?

I really can’t guess! Will the hipster crowd be lured this far south in search of cheaper rents? Will there be a hipster crowd in a decade? I’ll still be here representing the unhip, so ask me again in 25 years. Whoever else is around then will, hopefully, appreciate that they live within the former boundaries of a town founded on the principle of religious freedom, and expand that tolerance on a broader scale, thereby keeping Gravesend a safe and inviting community.

You can purchase a copy of Gravesend, Brooklyn from Arcadia Publishing. It is also available from Barnes & Nobles, Amazon, and Borders.