Gowanus Superfund Town Hall: EPA Provides An Update On The Cleanup

GOWANUS – With cleanup efforts officially kicking off at the Gowanus Canal’s Fourth Street Basin last month, elected officials and EPA representatives hosted a town hall meeting at the Wyckoff Gardens Community Center Thursday evening to update locals on the Superfund project.

Congress Member Nydia Velazquez kicked off the meeting recollecting the 17 years she’s spent working on cleanup efforts for the Gowanus Canal.

“Like many of you here today, I have been working on this issue since 2000,” she said, “specifically seeking federal resources” to fund the cleanup.

She recalled that early on it became clear that the level of contamination and pollution required the federal government, “the power and authority of the EPA,” she said, to help identify the polluters and hold them accountable for the cleanup.

“Every step of the way through this process, one of my priorities has been ensuring that this is a community-driven process,” Velazquez continued. “That is why in 2002, we secured funding for the comprehensive community planning study for Gowanus through HUD (Housing and Urban Development Agency). It was completed four years later and led to the formation of the Gowanus Canal Conservancy. It was through this inclusive process, with much input from local residents and small businesses, that we finally saw in 2010 the designation of the Gowanus Canal as a Superfund site.”

Velazquez also praised the EPA for forming the Gowanus Canal Community Advisory Group which she said, meets monthly, follows every step of the cleanup process, promotes local dialogue, and helps to shape the cleanup process.

In another effort to involve the community in the cleanup process, Velazquez has asked the EPA to create a local job training program. “Starting in 2019, a lot of new jobs will be created,” she said. “I want the EPA to create a Superfund Job Training Institute so we can train able bodies that live in this area so they can reap the benefits of the economic activity that is going to happen here.”

The cost of the cleanup project is $506 million, according to the Congress Member. “When [the federal government] cut the Superfund program by $380 million, we restored the funding. For 2017, the funding for the Superfund was $1.08 billion and we are on track this year to approve a similar amount or maybe slightly higher. No one should be concerned that the Superfund program will not have the money to continue the work that we are doing here,” she assured everyone in the packed room.

“We are cleaning up the canal the right way, in a manner respectful of community needs…. We have a long way to go, but today, the pilot dredging marks an important milestone, and I am proud we have come this far in implementing the cleanup design,” Velazquez concluded.

Natalie Loney, the EPA Community Involvement Coordinator, followed Velazquez providing a history of the Canal and information on how it became a Superfund site.

The Gowanus Canal was a major transportation route after it was completed in the 1860s, with barges transporting goods including marble, brick, wood, coal, etc., through the waterbody, with gas plants, mills, tanneries, and chemical plants dotting its shoreline.

Multiple manufactured gas plants located along the canal, took coal, heated it up, and used the gas produced to light people’s homes, Loney explained. “A byproduct of that coal processing is coal tar,” she added, much of which can be found at the bottom of the canal today.

“Very soon after the canal was built, it was declared a nuisance by the Board of Health,” she continued, with locals dumping garbage into the canal contributing to the pollution. Since the canal at Butler Street is a dead end, there was no natural flushing of the waterway. Loney said to resolve this, the city built a sewer outfall at the head of the canal, sending sewage into the canal to help flush it, adding further contaminants to the body of water.

The EPA conducted a Preliminary Assessment and Site Inspection and determined that the Gowanus Canal did qualify for the Superfund site list in 2010. This meant that the canal was now eligible for Superfund funding for its cleanup if there were no Potentially Responsible Parties (PRPs) responsible for the contamination. Loney adds that responsible parties were identified and will be funding the cleanup of the canal.

“The contamination is so extensive in certain parts of the canal that it’s also migrated down into the original native sediment. If we scraped off all of the sediment from the bottom of the canal, there are still areas where the contamination is so extensive that the original bottom of the canal is also contaminated,” Loney explained. “This sediment can be anywhere from about 10- to 20-feet thick over the entire surface of the canal, however that contamination in the native sediment goes several feet down, 100-feet in certain areas.”

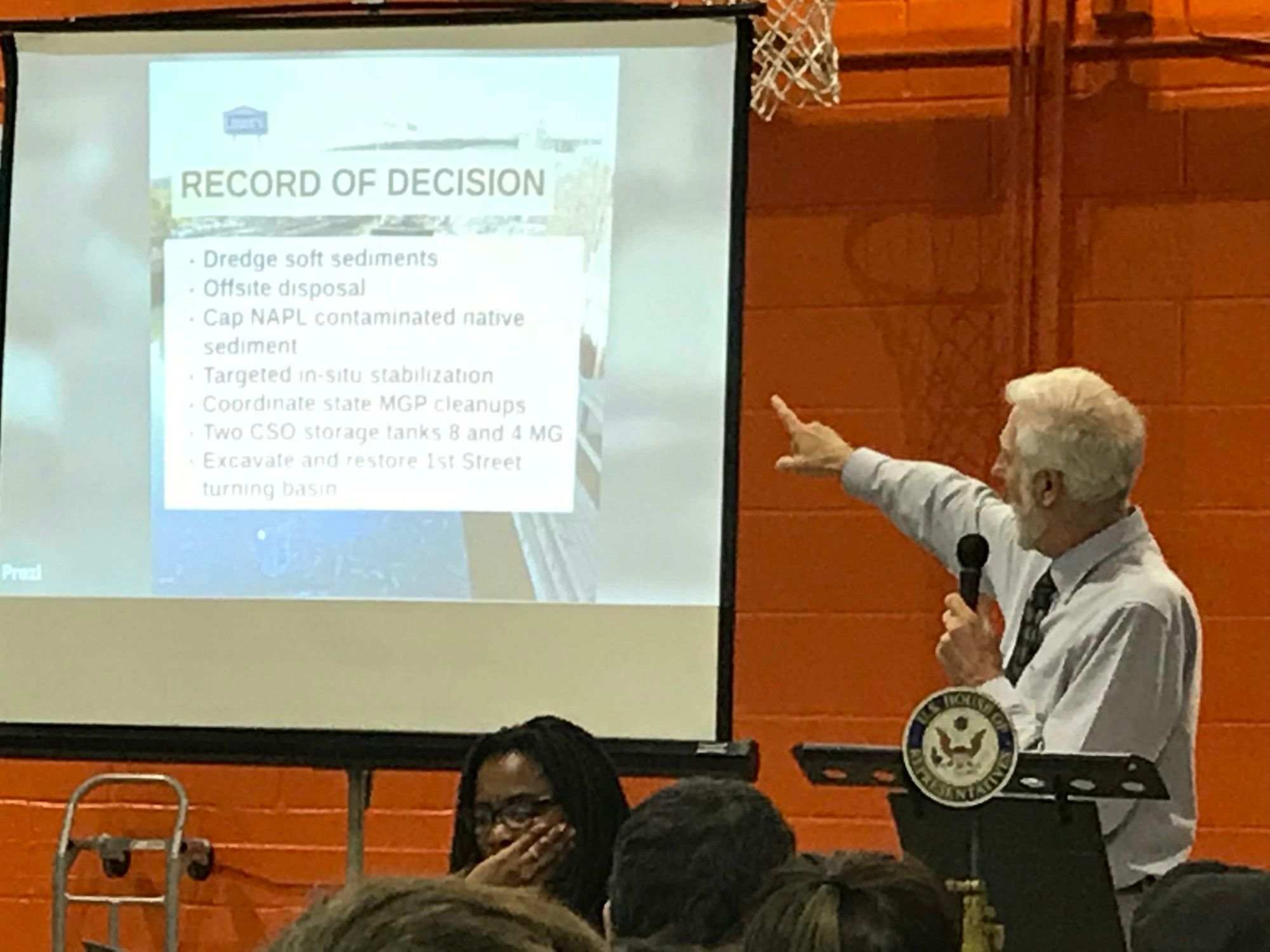

After placing the Gowanus Canal on the Superfund site list and conducting a remedial investigation and feasibility study that looked at sources of contamination at the canal and possible ways to address them, the EPA came out with a proposed plan which laid out their approach to cleaning up the canal. That document was approved in the Record of Decision, Loney concluded.

Walter Mugdan, the EPA’s Superfund Regional Administrator for Region 2, then took the mic to discuss what the Record of Decision includes.

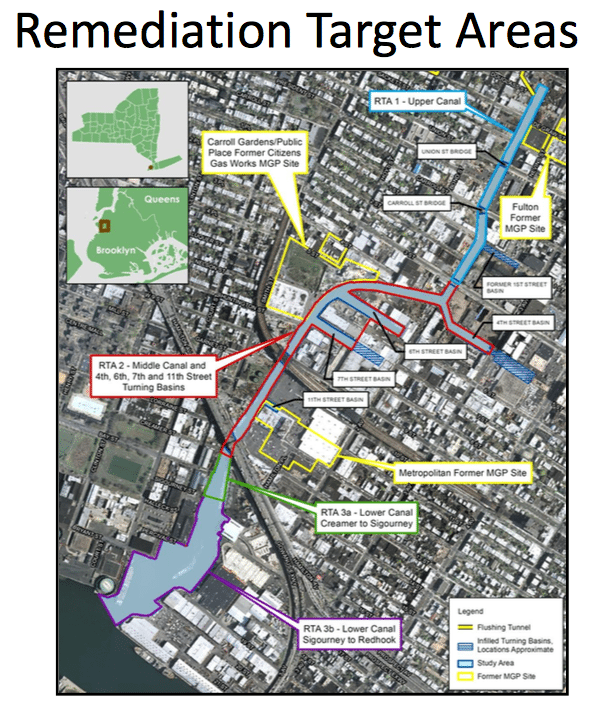

The canal cleanup is divided into four sections, or Remediation Target Areas (RTAs), starting from the top at the northern end and running south down to the harbor. RTA 1/Upper Canal has intermediate levels of contamination; RTA 2/Mid Canal has the highest level of contamination; RTA 3A/Lower Canal has the lowest level of contamination; and RTA 3B/Lower Canal also has the lowest level of contamination, however the contamination is deeper.

Mugdan discussed the EPA’s plan to dredge up the “black mayonnaise” at the bottom of the canal and to cap the bottom to prevent contamination from spreading. The work being done at the Fourth Street Basin will serve as a pilot cleanup program to help evaluate and finalize further dredging and capping for the rest of the canal.

The pilot cleanup will help the EPA determine how to best remove debris from the bottom of the canal; install steel sheeting to support existing bulkheads during excavation; stabilize areas with higher levels of contamination; dredge contaminated sediment; and install a multi-layer protective cap on the original canal bottom.

National Grid is one of several PRPs since it purchased Key Span a few years back, which in turn purchased Brooklyn Union Gas (BUG) in the 1990s, according to Mugdan. Of the three, BUG was the original polluter of the canal, but National Grid is legally liable and is now largely responsible for the next steps of the cleanup and designing a “canal remedy.”

Along with the canal cleanup, National Grid will be responsible for removing contamination from beneath Thomas Greene Park (225 Nevins Street). The playground is built on top of a former manufactured gas plant. Underneath the pool area there is a substantial amount of coal tar that needs to be removed, Loney explained earlier in the presentation. Mugdan quickly pointed out that the years-long project would not begin until a temporary pool is installed at the park.

National Grid will also be responsible for designing and installing the Fulton cutoff wall, a thick bulkhead that will be installed at the head of the Canal and run to Union Street on the east side to prevent contaminants from migrating from the site where the Fulton Manufactured Gas Plant once operated.

The design and installation of two Combined Sewage Overflow (CSO) Holding Tanks will also be on National Grid. The CSO tanks will hold excess rainwater and sewage during heavy storms, preventing it from flowing into the canal. The tanks will then pump the runoff to a wastewater treatment plant.

One CSO tank will hold 4 million gallons of rainwater and sewage and will be placed by the Fourth Street Basin. The second CSO tank will hold 8 million gallons of runoff and will be located at the head of the canal at Butler Street, possibly displacing some property owners and forcing the demolition of the historic Gowanus Station building located at 234 Butler Street.

During the Q&A portion of the town hall, several residents of nearby public housing developments including Wyckoff Gardens and the Gowanus Houses expressed their concerns about the sewage system, flooding in their homes, and the air quality and pollution during construction.

Mugdan assured the residents that the construction sites are constantly monitored for volatile contaminants and said that work would stop immediately if any dangerous levels were found. The residents were not satisfied with this answer and urged him and the EPA to consider developing an alert system for neighbors and NYCHA residents.

Learn more at the EPA’s Gowanus Canal Superfund website and at the EPA Gowanus Canal Facebook page.