Five Questions for Ditmas Park Author Jake Siegel

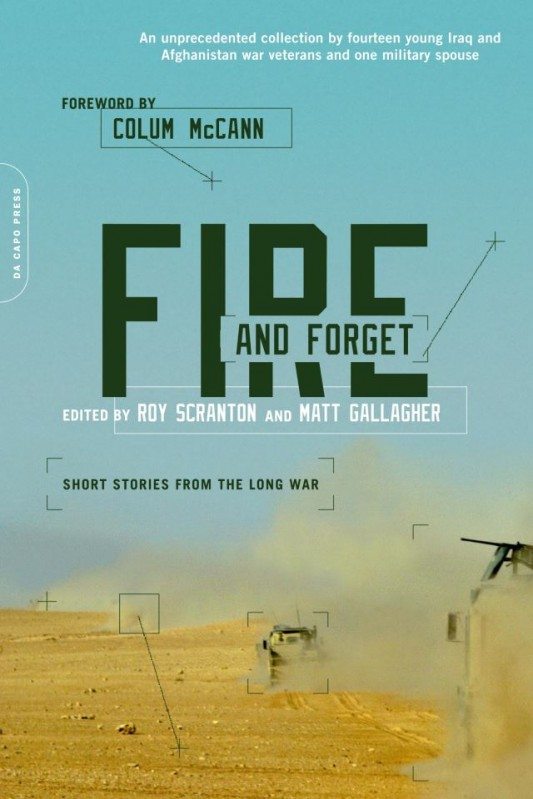

One of neighbor Jake Siegel’s short stories was just published in Fire and Forget: Short Stories from the Long War, an anthology of fiction written by Iraq and Afghanistan veterans, and a non-fiction piece about his time in Iraq ran today in the New York Times. He’ll be reading at Sycamore tomorrow, Saturday, March 23 at 7pm along with several other contributors to Fire and Forget and one poet who he says is “not part of the book but a great reader.”

On the eve of what should be a really great event, we asked Jake a few questions about writing and about growing up in Ditmas Park.

How much different is your process for writing non-fiction versus writing fiction?

Usually in non-fiction I have a pretty good idea at the outset of what I’m trying to say. Then it’s a process of shaping the story, creating the right transitions and editing the individual lines until they are taut enough and have the right sound. It can be more or less work but it’s not agonizing like the fiction. I don’t know what I’m trying to say with fiction until I start to say it and even then there’s no guarantee that I believe myself.

How did your inclusion in this anthology come to be?

One thing you learn from comic books is to stick to your origin story. Roy Scranton, a friend, co-editor, and contributor [who will also be reading at Sycamore], wrote the definitive account of the anthology’s inception in the preface to the book and I’d like to quote it here:

“We’d met, the five of us, through the NYU Veterans Writing Workshop and other vet events in New York City…We came from different places and had different wars, but we shared a common set of concerns: good whiskey, great writing, the challenges and possibilities of making art out of war, and the funny gray zone we found ourselves in, where you shape truths out of fiction pulled out of truth — which might only be the illusion of truth in the first place.

We made a date for the White Horse, where this anthology took root. Over the next year, we collected stories, soliciting, nurturing, pruning, trying to put together something we could feel proud of, something if not representative, at least vivid enough to inscribe on the wars our mark — our signature.”

Roy’s got the final story in the book, “Red Steel India,” and his preface beautifully explains who we are, what we were trying to do with the book and why we felt the need to tell these stories. Let me quote from it again:

“On the one hand, we want to remind you, dear reader, of what happened. Some new danger is already arcing the horizon, but we tug at your sleeve to hold you fast, make you pause, and insist you recollect those men and women who fought, bled, and died in dangerous and faraway places. On the other hand, there’s nothing most of us would rather do than leave these wars behind. No matter what we do next, the soft tension of the trigger pull is something we’ll carry with us forever. We’ve assembled Fire and Forget to tell you, because we had to — remember.”

How much of your own experiences influence your writing?

My own experiences include the best parts of other people’s lives and ideas that I have stolen. Stolen from friends, detective novels, glimpsed moments and the ones that were hard and inescapable. Some bits I’ve had for so long now I’ve forgotten that they weren’t once mine, then there are things I’ve lived through that now feel like a story I tell myself. My life is no less vast and unpunctuated than any other life, muddled but still shaped by everything that’s ever haunted me. Joy, cheap thrills, beauty, anguish, courage — whatever lasts long enough to remind me of myself and the place it came to me from.

You’re in a family of writers. Do you ever read each other’s work while it’s in progress? If so, who’s the toughest critic?

We all read each other’s work all the time. I just edited something for my father two days ago. It’s not an event; he’ll be talking about the Knicks then ask me to move something heavy, then sit me down to read whatever it is he’s working on at the moment. My mother is the best line editor in the family and the nicest person any of us knows, too nice to be as ruthless towards her son as I might sometimes require from an editor. Harry, my brother, and a senior editor at the Daily Beast, is the toughest and best critic I know. He’s unsparing in the right degree, instinctively attuned to the shape of a story and its payoff, and allergic to pandering. Nothing I write goes public before I’ve gotten his edits and made my changes.

Growing up in the neighborhood, you’ve seen a lot of change. What’s one thing that’s gone that you miss, and one thing we’ve got now that you’re glad it’s finally here?

As a kid my grandparents would come in from Jersey and take my brother and me to George’s Diner every Sunday. The old George’s when it still stretched onto Cortelyou and had a full menu and a crack cook. I can’t go to George’s anymore, it’d be like visiting a prizefighter in an old folks home — too sad and not what you paid for. I miss the old D train too; the Q will always feel like an impostor. I think that my mother would want me to say that I’m glad the farmer’s market is finally here and I do love the farmer’s market so that’s what I’m saying. It’s nice to have a bagel store stick around for more than a year.

Jake is currently at work on a novel that should be out some time in the next two years, and a collection of short stories that could be out even sooner. He’ll be reading at Sycamore (1118 Cortelyou Road) on Saturday, March 23 at 7pm.