Surrealist Artist Vincent Castiglia Talks Tattoos, Bloodletting & Growing Up In Bensonhurst

“Every painting is intrinsically a part of me,” says Bensonhurst-born tattoo artist and surrealist painter Vincent Castiglia.

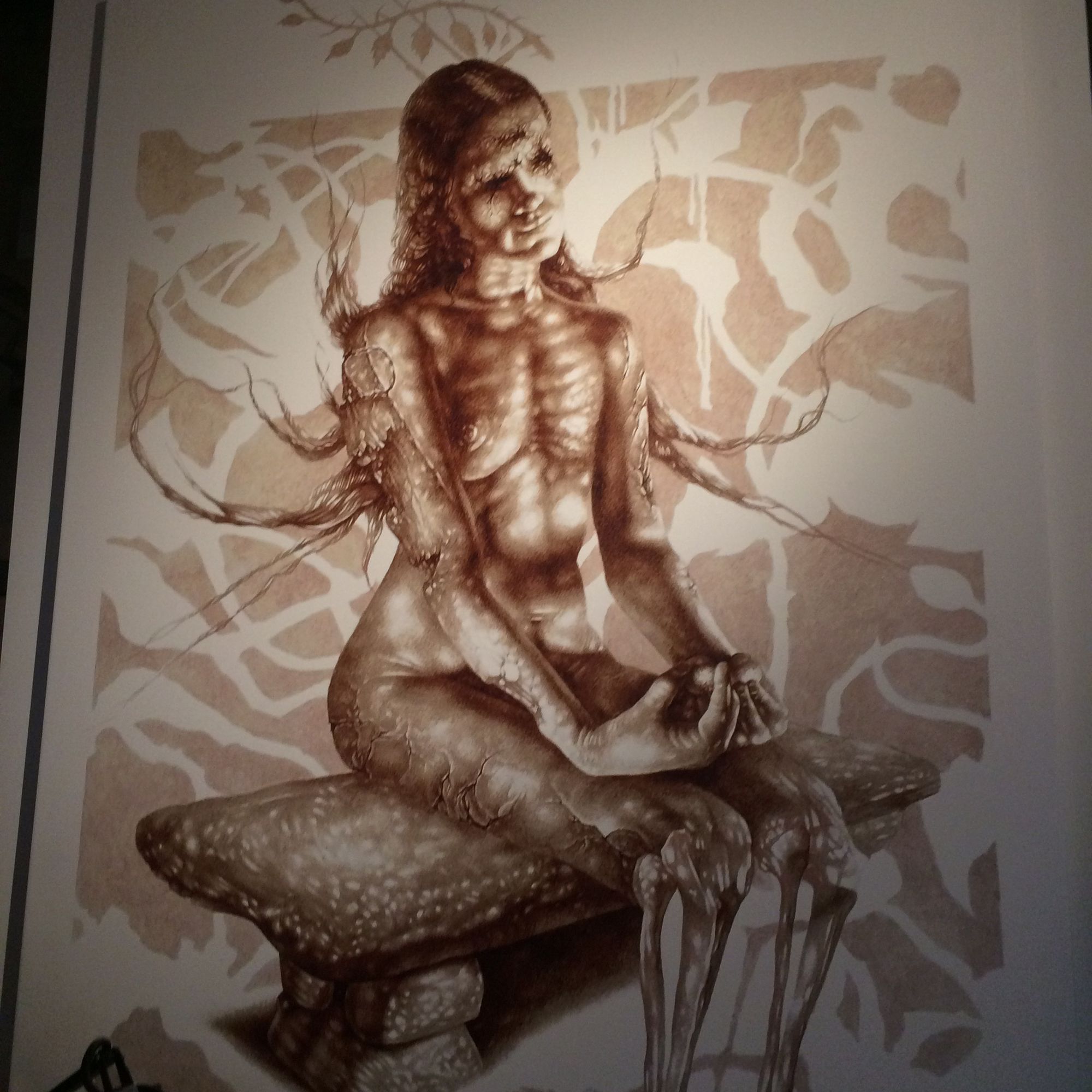

The artist — whose works sell for up to $25,000 — creates his avant-garde art using a peculiar medium: his own blood. Castiglia’s website describes the process:

In the privacy of his studio, Castiglia practices a kind of modern-day phlebotomy, siphoning the life force which contains his own psychic energy, while giving it an outlet and form. In doing so, he dissolves the barrier between artist and art in a most literal and immediate sense.

Castiglia, who calls his pieces “hemorrhages,” gave us a tour of his dual purpose art and tattoo studio in Manhattan’s Financial District last week. As we watched him work, Castiglia opened up about tattooing, the process of blood painting, and how his Bensonhurst years inform his deeply personal artwork.

What was it like growing up in Bensonhurst?

My mother and I first lived in an apartment on 23rd Avenue and 81st Street. Growing up in Bensonhurst in the 90s was a double-edged sword. New York was still New York, you know? Bensonhurst was like a “Goodfellas” sequel that you couldn’t change the channel from. There were the wise guys and the wannabe wise guys. It was kind of crazy, but it was cool.

I made a lot of friends, did a lot of running around and getting into some trouble. Nothing too crazy. There’s a certain nostalgia I get going back there. I have a lot of bad memories of the area. But when I say bad memories, it had more to do with my home situation rather than the neighborhood itself. It’s changed a whole lot, man. I go back there to see one friend. It is very culturally different, which is cool, but it is certainly not how I remember it.

What were some of your favorite places to hang out?

John’s Deli on Stillwell, I was around the block from there. I did a lot of hanging out in the street (laughs). Fiorontinos that’s a place. I was living, right before I moved out, I was living on West Street and Avenue U.

Avenue U was jumping. I was sandwiched between two funeral homes. Bensonhurst in general isn’t the most scenic place, but that place was beautiful. I loved it there. People attending a funeral are always nicely dressed and there is this air of sanctity. It probably made itself into my work at the time. Brooklyn, New York, was kind of a rougher place at the time. If you couldn’t hold your own, you were gonna get run over — it was survival of the fittest. I didn’t turn out to be a violent asshole, which a lot of the natives were, but it hardens you in a way that changes things. That apartment on Avenue U was my little safe space.

Bay 35 Street and Bay 50th Street. That’s where everyone hung out. Friday or Saturday we hung out there. People who were not supposed to be there, you know. Lots of people that did not live there. Systems and a bunch of dudes trying to be hard, listening to free-style.

L’Amour was fucking awesome. I did not get the opportunity to see Slayer. The metal scene in the mid 90s was violent and very dangerous. There would be deaths, there we ambulances waiting outside. I kind of miss that time.

I can’t do an interview about Bensonhurst without mentioning Mikey Tattoo in on 16th Avenue and 62nd Street. Mike Perfetto. Mike was just a legend, you know. Very low key. He doesn’t have a website still. He has been tattooing since the dawn of time, and he’s drinking from the fountain of youth. He did my first tattoo and he influenced my early work. He tattooed about 60 percent of my body. It was therapy and everything wrapped up into one. When I started tattooing, everything I did was a variation of everything I learned from him early on.

What was it like tattooing there?

Tattooing in Bensonhurst, I dealt with a lot of people, all the neighborhood people. I would refer to it as my studio. It was difficult, because if you take shit from anyone, they’ll run right over you.

At a certain point in time, I was dealing only with seedy characters like drug dealers; the only people who could afford tattoos were drug dealers. I was making a living, so I couldn’t complain. It was a bad thing at that point. There’s plenty of good that was there and is still there. The tradition and the Old World vibe is great, but it came with some other stuff.

Can you tell us a little bit about your art and its nuances?

I work in a particularly unique medium, which is human blood. I would describe the world as figurative surrealism; I’m painting human figures. The work is inspired by life and death. I’ve referred to the paintings in the past as hemorrhages. I would define a hemorrhage a the bursting of a vessel, and that is what it was like, I was dealing with pressures for far too long and finally I burst through my art emotionally. The substance was a disconnect until I started experimenting with blood initially. It felt like a personal truth was being communicated and it was just profound. It couldn’t be communicated in any other means. When I connected with it, I fell in love with it. It was communicating what was going on the inside.

It is painful to get the blood, and there was a lot of pain in the art. For me it was the completion of a conceptual circle between the art and the medium. It blew me away and I started working with it exclusively. I started using it experimentally in small amounts in 2000, and I was doing pen-and-ink drawings and incorporating blood into the figures. I was doing that for a few years, and in 2003, I did my first painting using only blood. That’s when I said, “Wow, this could really work on its own.”

You are so used to fitting into the boxes of society as to what you can use or what you can make, it took a few years for me to realize, fuck, I can use this exclusively and take it far as I can. I started putting basically all the time that I had going into it. It was a new frontier for me. I would work all night and into the next day, I loved it so much.

How does the process work?

The concepts occur it two ways. Either it’s spontaneous or it is being inspired by a particular thing. A circumstance that it is in my life that is significant enough to be address on canvas. I work from live models. I have them come in, I photograph them. The background, the decaying flesh and bone, comes from imagination. The process has changed since I have become more digital. From the digital concept I create the finished painting.

The consistencies range from being all blood to mostly water. The blood gets more opaque as it oxidizes and decomposes. Fresh blood can only be so dark. Older blood becomes a paste over the course of a month or two. That is how I get the density. I do dozens of passes over a painting so they take a very long time. I don’t seal it or fix it in any way, I don’t want to mess with its constitution. The work by itself will hold up. I had no clue when I started working it if it would have archival qualities. The same thing that is in blood is in paint that keeps the paint. Blood is the most personal pigment a artist could ever use. There’s cave paintings done over 50,000 years ago done in animal blood that have survived. The blood will survive many generations without fading.

How do you separate your art from your tattooing?

I think they compliment each other very well in the sense that they are diametrically opposed. I am making art in both places, but tattoo clients come in with certain ideas and images. It is about them and illustrating that for them. It is the purest form of art for me. Tattooing has developed and sharpened my drafting skills and that draftsmanship has been applied to canvas. The one thing I will say that they share is the unforgiving nature of the medium. It is one shot, one kill. It’s the same thing on canvas as it is on skin. It is exact in nature. That would be the thing that they share the most.

How does it feel that someone can own something that is a piece of you? Do you think people understand the nature of your art?

I have to say that it’s about split. Some people understand the piece and what it is about or they connect with it viscerally and are just attracted to it. The work is so personal that I’m not sure that it can be gotten unless I was sitting down and explaining it. That would be illustration — if you could understand the painting just by looking it at it, then it’s just illustration.

Do you have any friends left in Bensonhurst?

I have a couple of friends left. Every time we speak it’s like, wow. It’s a matter of preference. I preferred not to be there long before I got out of there. Some people like it there and are comfortable. The people I grew up and ran around with have come into a lot of hard times. It was a neighborhood thing. You hung out and you got high — that type of thing. So yeah, that’s a dark alley.

The racism was just un-fucking-real. In the neighborhood there was an “us and them” mentality, which I wasn’t a part of. I lived across from Marlborough projects and you never saw the residents from there. You would hardly see black people.

Are you still nostalgic about the area?

I have a nostalgia connected to the area. I go to Fiorentinos, I have a chicken francese and baked clams (what are those fucking things called?) and that’s about it. It’s surreal. I was considering that stuff recently. I’m a long way from fucking Gravesend right now and it kind of makes sense. Either the environment consumed you, or it pushed you to work even harder.

To see more of Castiglia’s art, visit his website.