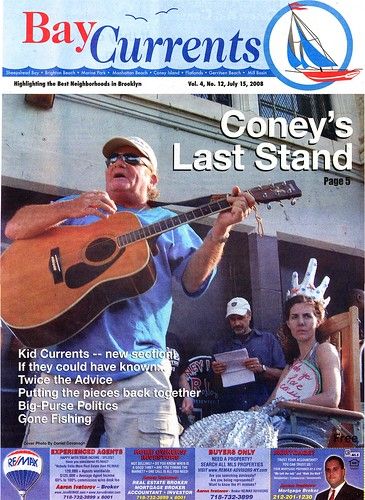

Bay Currents: Coney's Last Stand

The latest issue of Bay Currents features a front-page article by yours truly covering the June 24 Coney Island Development Corp. scoping hearing. The full text of the article is below:

If there’s any one word to describe the development of Coney Island, it’s confusion.

Private developers, city agencies, development advocates, union groups, artists, councilmen, community board members, amusement operators, public housing advocates, mayors – real and phony – and a white-suited anti-consumerism reverend all vying for the spotlight… what are we even talking about anymore?

Everyone seems to have his or her own plan. The main private developer, Thor Equities, has one. The city agency Coney Island Development Corporation (CIDC) has one, and had another one before that. A myriad of groups are pushing their own proposals that cover their interests – affordable housing, proper infrastructure, job and career training, revitalization strategies to “save” outdoor amusements.

This confusion was palpable at the June 24 hearing at Lincoln High School on the latest CIDC proposal. The agency – charged with overseeing a new development plan for the neighborhood – has worked on a proposal since 2003, with over 200 meetings and more than 1,000 people providing insight and opinion. But that plan was scrapped in April, when the city used CIDC’s name to announce an adjusted proposal without consulting the agency’s directors. The newest proposal appears to give Thor Equities a lot of what it had wanted, allowing them, for example, to build towering 30-story hotels on land that the previous plan zoned for smaller retail.

The inevitable outrage began in the weeks before Tuesday’s meeting, and clamored to a peak with CIDC director Dick Zigun’s open letter of resignation to Mayor Bloomberg. Zigun, as founder of Coney Island USA, was the only director representing the amusement industry. He berated the city for its “undemocratic” tactics in its move to reverse course and push a new plan without the input of the directors or the public. “I urge you to withdraw this deeply flawed plan and cancel this hearing, but as it stands I cannot leave my name on it,” wrote Zigun. “I am particularly disturbed that the Directors of the CIDC have had no opportunity to discuss or vote on these substantial changes to our Strategic Plan – which was the result of years of work and which had achieved widespread neighborhood consensus.”

Zigun’s high-profile resignation served as a clarion call to the numerous concerned residents and organizations. Hundreds turned out on Tuesday, packing into the Lincoln High auditorium.

Zigun told the Bay Currents his goal is to “get politicians to keep their own promises and keep their own plan.” He wants nothing more than to revert to the agency’s previous plan, which he has some misgivings about, but still believes in because it was developed after several public hearings and compromises.

But that was hardly the sentiment of most who came out to the late-June meeting, which attracted over 100 speakers and went on for hours into the evening.

The bottom line of the controversy: Most agree that Coney Island needs to be revitalized and developed, but residents and amusement advocates fear threats to its “kitschy” culture.

George Shea, chairman of “Major League Eating” – the committee that oversees Nathan’s Hot Dog Eating Contest – told the crowd, “Corporate amusements do not represent the soul of Coney Island. In Coney, you are allowed to do things that are odd, and even a little bit offensive.”

He expressed the fear of many that increased “entertainment retail” are a bait-and-switch that will impose chain franchises into the heart of Coney Island.

The crowds outside and inside the auditorium held signs declaring, “Keep Coney Amusing” and “Coney Island – Not Condo Island,” and the flamboyant Reverend Billy’s sermonized on the evils of consumerism and the demons of corporate amusement

Added to the fears of a McDonald’sization of Coney, is a litany of concerns about the future direction of the neighborhood: the plans provide jobs, not quality careers; public housing is not expanded, and affordable housing is not defined; traffic congestion needs to be addressed; area hospitals and schools may not be able to take on the expected population influx from housing; utility infrastructure in an area that already experiences frequent brownouts will be further strained.

The threat to Coney Island is more than just the extinction of its freak culture. Coney Island is not just an amusement district with a particular culture – it is the last remaining vestige of a bygone era on Brooklyn’s Gold Coast, which is what oceanfront Brooklyn was once called. It’s a symbol of a day before condos and large-scale luxury residences lined the borough’s waterfront; before neighborhoods became experimental labs for public policy wonks; of when communities had distinct flair and flavor, and weren’t just homogenous landing zones for garish structures with neighbors who don’t know each other’s names. While communities from Williamsburg and Greenpoint down to Manhattan Beach and Sheepshead Bay have borne witness to an explosion of gentrification and housing development, Coney Island has largely remained the same.

Coney Island has a unique character in its persistently individualistic, colorful-but-rugged way, and any form of development is going to alter the character of the neighborhood forever. But those cultural changes are only a superficial backdrop to a real, genuine debate over the effects of changes that have come and gone across all of coastal Brooklyn.

Coney is the holdout.

Coney is the last stand.