2800 Coyle Street: Co-op Of Corruption

Residents of a Sheepshead Bay co-op apartment building have turned a series of disagreements into an ugly, bitter, and personal fight pitting neighbor against neighbor.

The worst part is, it can happen in almost any co-op.

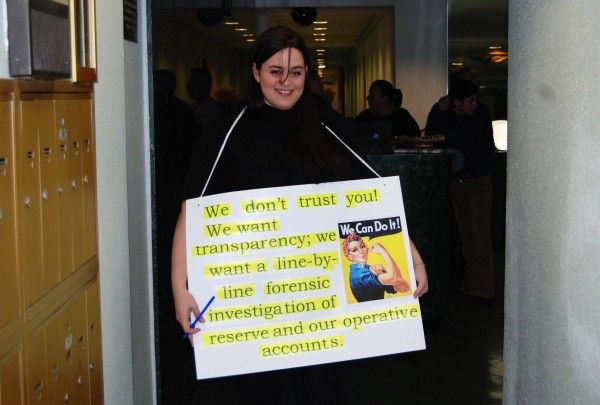

The entrance to 2800 Coyle Street sits about halfway up the block, between Emmons Avenue and Shore Parkway. Last Tuesday, January 26, all was quiet on the sleepy street. But inside, about 20 disgruntled residents gathered in the lobby donning protest signs and trading war stories about the building’s overseers.

They said they were there to oppose the “Tyranny and Corruption of the Majority Board of Directors,” specifically five members of the eight member board that they say run the gamut from incompetent, to corrupt, to an organized crime syndicate. (Technically the board has nine members, including one appointed by the sponsor, LeFrak organization, who remains neutral.)

“It’s just amazing the tactics that they use,” said Diane D’Agostino, a former vice president of the board. “It’s like I’m not even living in the United States of America. I have never been treated so horrendously as I have been by this board. It’s terrible.”

From a thick folder, D’Agostino produced documents that she and other residents say are a trail of fraud, embezzlement, extortion, and a criminal-level conspiracy to cover it all. Supporters of the minority board are chock full of anecdotes about harassment, nepotism, and waste.

There’s the girl who was allowed to have a dog if she signed a proxy vote in support of the majority board, and the man who was refused approval to buy his mother-in-law an apartment because he opposed them. There was the time an elderly blind woman with a dying son needed some documents approved but was told to first sign a similar proxy, and the dozens of affidavits from people who say they were tricked into recanting their support for a special meeting to dethrone the board when they needed repairs done to their apartment.

“It’s bullshit,” said Konstantin Zheleznyakov, the building’s treasurer at the time we spoke. “It’s just these people. Three hundred people live here, but this is twenty. I’ve done a very good job for this building. I saved money. Everything. The previous times were full of corruption.”

Upstairs in his apartment, with his daughter serving as translator, Zheleznyakov shows me a folder like D’Agostino and begins pouring through it. The board’s documents, he said, show that many of the things they are accused of happened before they were board members and are actually crimes of the previous board. In other cases it’s misunderstandings or results of mistakes in paperwork. And in most cases it’s outright lies, told by the minority group so they can regain control of the building.

To be fair, I can’t make heads or tails of the documents on either side. Their arguments sound eerily similar, their accusations near reflections, and their mutual distrust palpable.

Making matters worse, there are no oversight agencies for co-ops to look into complaints. Without verification, distrust festers and neighborly relations fail. In my discussions with people on both sides of the issue, actors on either side were described as idiots, animals, beasts, witches, ugly, fat, liars and on and on.

Residents have tried complaining to the Attorney General, the District Attorney, and even the FBI, but the allegations are either too small (FBI), out of their jurisdiction (Attorney General), or the office is understaffed to handle the complaints (District Attorney).

“They want a whole case laid out in front of them,” said Ronnette Gleizer. “But how can we make a case without access to the files?”

“There’s no one that can give an answer. There’s no one that really cares,” said former Board President Sophie Zimilevich.

Meanwhile, renters and disinterested shareholders are caught in the middle.

“It’s a pig sty, there are cockroaches, cigarette butts, and the hallways are never cleaned, the incinerators never cleaned,” said one renter who asked not to be named.

(Article continues after the photo)

The protest was scheduled in advance of a special meeting called that week to displace the majority members of the board.

The meeting kicked off at 7:30 p.m. on Thursday night, and before attendance was even taken residents were accusing each other of malfeasance.

It’s no surprise. Merely getting to that point was months in the making, as the minority group solicited signatures from 25 percent of shareholders (In co-ops, unit owners do not actually own the property. Instead they own shares in a corporation that owns the building.). During the process, members collecting signatures say they were followed by board members bent on intimidating residents out of signing. The police, they say, were called four times and the board members told to back off.

After residents pooled together $5,000 to hire an attorney, they collected signatures from 30 percent of shareholders. The minority group said they were denied the right to meet as the majority board – needed for a quorum in any meeting – would not attend. Ultimately a court order was required.

But the four-hour special meeting at the Golden Gate Inn did little to solve the problem. The same laws used to govern corporate structure apply to most New York City co-ops, a confusing mess of procedures and formulas called the Business Corporation Law.

In the end, though nearly 90 percent of outstanding shareholders were represented and the opposition group had a clear win of 54 percent of those votes, they only were able to remove one of the four members they targeted – the board’s treasurer, Zheleznyakovst. And until the next election, that seat will be filled by an appointment of the majority board, meaning there has been zero shift in the building’s power structure.

The confusion of the BCL angered many residents, who don’t understand why an archaic corporate document is applied to a residence, though none of the protective agencies are tasked with overseeing them.

“If we’re not governed by any government agency because we’re a private organization, why should the BCL override our black book?” asked D’Agostino. “Why would the BCL get involved and put a smokescreen over our election?”

Many at the special meeting also were plainly disillusioned – some in tears – wondering why the board members can still cling to power when the majority of residents want to see them tossed out.

But worse than the confusing legal mess (and a lawsuit has been promised by the opponents) is the damage the election has done to those who made their opinions known. D’Agostino said the board, which governs residential life for the building’s 157 units, is a vindictive group of people. Unhappy residents won’t be able to sell their property, will be hassled about repairs, and will be harassed and fined at every opportunity.

“I feel like Big Sister is watching,” she said in reference to the board’s president, Svetlana Marmer. “The ones that did come [to the meeting] came out in the cold, they supported us, they did all this work. And now I’ve put them in jeopardy. They made themselves sitting ducks.”

D’Agostino has already approached State Senator Carl Kruger and Councilman Lew Fidler and others about getting protection for the building’s residents, but it doesn’t appear much will be done.

Though the story is far from over, the hope is that 2800 Coyle Street will serve as an example to lawmakers about the lack of regulation and oversight from city and state authorities. With an inexperienced board of volunteers, mismanagement and abuse are hard to tell apart. Independent oversight would reestablish crucial lines of trust.

“The people are not bad,” said current minority board member Neil Thompson. “There are people doing funny stuff, but nobody’s showing us a document by the city or state that either’s documents are wrong or right. So it’s all politics. It’s people’s attitudes that run on their emotions and not their business sense.”