Where Was The MTA?

THE COMMUTE: Having retired from the MTA in 2005 and not actively working in Planning for quite a number of years, I do not often attend Planning conferences. The last ones I attended were a series of workshops held over a four-year period from 2002 to 2006, sponsored by the New York Metropolitan Transportation Council, the agency responsible for doling out federal funds in this area. Those sessions part of the Southern Brooklyn Transportation Investment Study looked forward to 2020 and primarily focused on medium and long range planning. That study, costing approximately $6 million, resulted in not a single accomplishment, because of the MTA’s refusal to concur with any of the numerous suggested bus or rail improvements. They stated that they do their own planning and no one tells them how to plan.

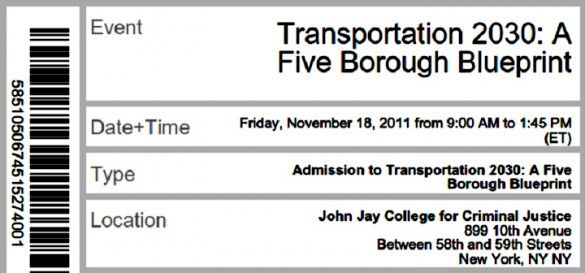

Similarly NYC DOT, another participant in that study, would only support additional bicycle routes and would not concur with most traffic or freight recommendations, except for one or two. The only other recommendation resulting from that study was that additional ferry routes would not be economically sufficient. The city ignored that recommendation, later sponsoring several experimental ferry routes. So, several weeks ago, when I learned of a transportation planning conference entitled “Transportation 2030: Five Borough Blueprint,” sponsored by Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer held at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, I was a little hesitant.

The conference was mostly a disappointment because important subjects were not on the agenda and the conference offered little opportunity for discussion. It merely presented Select Bus Service (SBS), also referred to as Bus Rapid Transit (BRT), Congestion Pricing, and increasing bicycling as panaceas to solving our transportation problems. A few worthwhile points were raised and I was more impressed with the community activists on the panel of the afternoon breakout workshop I attended.

Morning and Afternoon Sessions

Introductory remarks were provided by former NYC DOT Commissioner Iris Weinshall, Manhattan Borough President Scott Stringer; former Port Authority Executive Director Christopher Ward, and current NYC DOT Commissioner Janette Sadik-Khan. The focus of the conference was investing in the outer boroughs — ironic since it was sponsored by Stringer. Although much of what was discussed involved the MTA, the agency sent no representatives. Rather than going into a discourse as to why, let that be a discussion for the comments.

The panel for the morning session was comprised of Christopher Ward; Samera Barend, vice president and executive director for Strategic Development for Public Private Partnerships & Alternative Delivery-North America; Gene Russianoff, senior attorney, New York Public Interest Research Group’s Straphangers Campaign; and Peter Torellas, chief technical advisor, Siemens. The moderator was Mitchell Moss, director, Rudin Center for Transportation Policy and Management. Moss is also a professor of Urban Policy and Planning at NYU.

The afternoon sessions consisted of concurrent workshops on various subjects. These were: (1) Parking Reform and Reducing Congestion; (2) Filling the Gap in the Transit Map, the one I attended; (3) Utilizing NYC Waterways; (4) Sharing the Street, Bike Lanes and Bus Rapid Transit (another term for Select Bus Service), and (5) Safer Streets.

The Morning Session’s Main Points

Mitchell Moss kicked off the discussion by stating that the MTA is in its best shape ever. Russianoff spoke of how far we have come since the 1980s when our system was literally falling apart and the importance of finding sources of revenue other than the fare given no help from Washington or Albany. (I question why that should be a given over the next 20 years?) Ward, opined how truck traffic is choking the city, stating how it will only get worse with the increasing number of deliveries due to the rise in internet shopping. He recommended clearer truck routes, and rescheduling deliveries to the times the streets are less congested, as well as stating the need for better government regulation in order to reduce truck traffic and double parking. Ward recommended that the Port Authority should be the agency tasked with managing and pricing truck deliveries. He also would like to see a bus garage built in Manhattan to eliminate nonproductive midday express bus trips to and from New Jersey.

Stringer spoke of the need for Bus Rapid Transit for the North Shore of Staten Island without mentioning better alternatives such as reactivating the North Shore Line with heavy or light rail. He also spoke of long commute times of 90 minutes from the outer boroughs to Manhattan. (Not mentioned were lengthy intra- and inter-borough trips that can take two hours where there are no subways.) Stringer also questioned why subway construction costs are so high in New York City, over $2 billion per mile, compared with London, where new construction costs only $700,000 per mile. He offered no reasons why other than not to blame labor unions and criticized Albany for shortchanging the MTA.

Sadik-Khan spoke of DOT initiatives: Pedestrian plazas to make streets more people friendly and increasing the number of bike lanes and bike share programs soon to be implemented where you will be able to pick up and drop off bikes for a fee at selected locations, as well as SBS. She also mentioned smart motion traffic signals that could determine when cars are approaching an intersection and reschedule themselves as needed. (I thought that was the only proposal, which holds much potential.)

Sandra Barend highlighted the importance of public private partnerships to stretch dollars. Other subjects mentioned in the general session were providing ferries between Manhattan and JFK Airport, and how we can use technology to benefit us. Presumably, these were discussed further in the afternoon sessions. The point was also raised as to whether we should spend money on new technology when we cannot afford to maintain the system, like adequately cleaning or painting subway stations?

Commentary

Providing more funding to the MTA through Congestion Pricing or tolling the free East River bridges and SBS were discussed as if they were panaceas. No alternative funding sources were mentioned, nor was making the MTA more efficient or accountable, the need to change the MTA’s culture, or expansion of the subway system.

Even if SBS were instituted along 20 corridors throughout New York City, that only represents a very small percentage of the more than 300 local bus routes in the city and would not solve most of the current local bus problems. The DOT harped on the statistic that SBS ridership has increased and bus travel times are faster, as if those are the only measures to indicate success. No mention was made if passenger trip times, the most important measure in my opinion, decreased. The data presented thus far by the MTA [PDF] suggesting success is severely lacking, yet SBS is being touted as the cure all for bus routes.

Other Subjects Not Discussed

There was no mention of the role of taxicabs, such as allowing car services or dollar vans to legally make pick-ups off the street, or else increasing the number of taxi medallions so that yellow cabs would pick up hails in the outer boroughs like they once did into the 1950s. A study released last week performed by college students showed that 27 percent of yellow cabs refused to take passengers from Manhattan to the other boroughs. TLC Commissioner David Yassky recently failed at an attempt to set up formal van routes where the MTA discontinued bus service and also toyed with the idea of street hails for non-yellow cabs. Thus far nothing has materialized.

This is an important area that needed discussion. Starting in the 1970s, or even earlier, yellow cabs making local trips in the outer boroughs became scarce and today, with perhaps the exception of neighborhoods near Manhattan such as Brooklyn Heights, finding a yellow cab outside of an airport is all but impossible. Affordable rideshare programs also offer some potential in sparsely populated areas where providing bus service is too expensive.

New York’s only ride share program exists between the airports and Manhattan. Other rides shares are legal only during emergencies, such as transit strikes. Yassky’s failure should not preclude future attempts in this area, despite the power of the taxi industry opposing any well thought out program having a chance of succeeding, which may cause the value of a taxi medallion to decline.

Afternoon Breakout Session — Filling The Gap In The Transit Map: Two Fare Zones And Transit Deserts

The session was moderated by Brodie Enoch, Public Transit Rider Campaign coordinator for Transportation Alternatives. The panel consisted of Jonathan Bowles, executive director, The Center for an Urban Future, who recently produced “Behind the Curb,” a report emphasizing the increasing importance of the outer boroughs as major employment centers; Tamisha Chevis, representing the Rochdale Village Community in Action for Better Express Service, a group she co-founded after last year’s service cuts; Elena Conte, organizer, Public Policy Campaigns at Pratt Center; and Joe Meyer, president and CEO, HopStop.com.

HopStop is an application for smartphones and computer devices such as the iPad, in which you can request and receive travel directions in many cities, based on criteria you specify. Meyer stated how they are constantly using customer feedback to improve their system. Tailoring it to specific user needs is the key to its success. A new feature has been added in which you can even request stroller-friendly routes. A permanent extensive database is maintained for all travel directions requested.

Aside from Bowles and Meyer, the moderator and panelists are all community organizers. The Rochdale group was formed when two people started talking on the street about how the MTA’s cut in express bus service in their neighborhood from 15 to 30 minutes resulted in the buses becoming so packed that passengers could no longer fit into the first bus, forcing residents of that large housing co-op in Southeastern Queens to wait an additional half hour to board a bus. Other than the express bus route, their only alternatives are slow local buses with long subway rides to Manhattan. The LIRR is quicker but trains are so overloaded that Rochdale residents cannot even squeeze into the trains during the morning rush hour. The additional cost isn’t even a factor for the residents because the trains are too crowded to permit the conductors to collect all the fares. They are even willing to pay the higher fare if there was adequate service, according to Chevis.

The situations Chevis describes should not even occur if the MTA were correctly applying its Planning Service Guidelines, which stipulate acceptable crowding levels. Although the MTA claims transparency, they have thus far refused to publish those guidelines on its website. They seem to only refer to them when cutting service to justify shortening or eliminating routes.

Meyer stated that we cannot rely on the MTA to solve our mass transit problems, and improvements will have to come from the private sector. He came to this conclusion after having offered to share his extensive database with the MTA for planning purposes. The MTA declined, stating that their numbers are correct while Hopstop’s numbers are wrong.

Conclusion

Just a few years ago we were focusing on 2020. Now it’s 2030. That is why I never put too much faith in these studies and conferences. We focus on the future to avoid solving the immediate problems we are facing today.

Bus riders have been complaining about bus bunching for the past 50 years as their primary concern, and no one addresses it. The MTA has shrugged off its responsibility of dealing with this problem and considers it out of their control, placing the blame solely on traffic. In reality, there is much they can do. Shorter overlapping routes and providing more short trips along lengthy routes instead of having every bus run end to end would provide some improvement. The MTA tries to avoid this because it would slightly increase operating costs.

In recent years, they have done the opposite by combining overlapping routes to reduce costs (e.g. B5 and B50 to form the B82), further aggravating bus bunching, or split routes (e.g. B61 into B61 and B62) to reduce bus bunching. But splitting routes without overlapping them also greatly reduces bus connections, increasing the number of three-bus two fare trips to complete trips. Dispatchers can also be used more effectively. It is not an issue removed from MTA control which has been their position.

Since 1980, the MTA has promised the bus bunching problem will be solved when bus tracking systems are in put place. Thirty years later, after numerous failed attempts, and millions wasted, we finally have a pilot program on the B63 called BusTime. It is scheduled to be expanded citywide in a few years, however, the MTA only promises it will let you know how long your wait will be for the next bus — not that it will be used to minimize bus bunching to reduce your wait.

Before you look around, there will be another conference focusing on 2040 and bus passengers will still be complaining about bus bunching and other transportation problems unless, either the MTA gets its act together, or is broken up so that control of the subways and buses is returned to the city with safeguards put in place so that whoever controls it will be responsive to its customers.

The MTA holds public hearings and makes presentations, but these are either legally required or are only for show since the vast majority of suggestions and problems mentioned by the public are just ignored. Once the public recognized this, they stopped attending.

Elected officials must also realize that if they continue to raid transit funds, it will not matter who controls our transit system. Meanwhile, the Lockbox Act, passed by both state houses, sits unsigned on Governor Cuomo’s desk. The purpose of conferences that focus on the future is to divert our attention from problems, which we have been ignoring for far too long and need to be resolved today.

The Commute is a weekly feature highlighting news and information about the city’s mass transit system and transportation infrastructure. It is written by Allan Rosen, a Manhattan Beach resident and former Director of MTA/NYC Transit Bus Planning (1981).