Sneak Peak: Take An Exclusive Tour Of ‘Sunset House Of Art’ Gallery

Come with us on this summer day to the Sunset House of Art, in the heart of, appropriately, Sunset Park.

Join Patricia Coleman, a director and writer on theater, who had taken a short stroll through her part of lower Brooklyn to meet up with her playwright friend Mark Blickley, in front of the undistinguished brick attached family dwelling.

Now, ring the bell with Coleman and Blickley.

Mari Biro, the House of Art’s 68-year-old tenant and guiding spirit, opens the door, welcoming the visitors in her pronounced Transylvanian accent.

Coleman and Blickley step inside, into of New York’s best concealed (and most revealing) oddities.

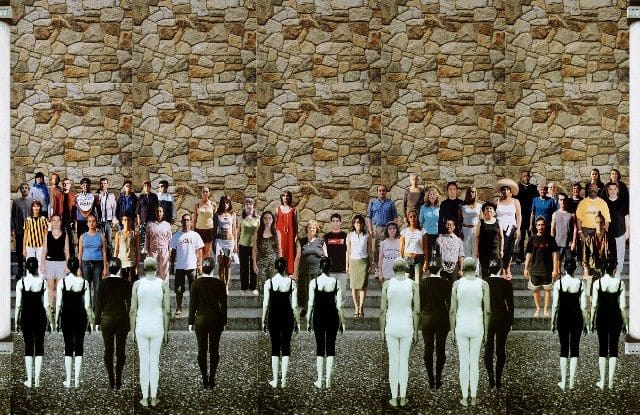

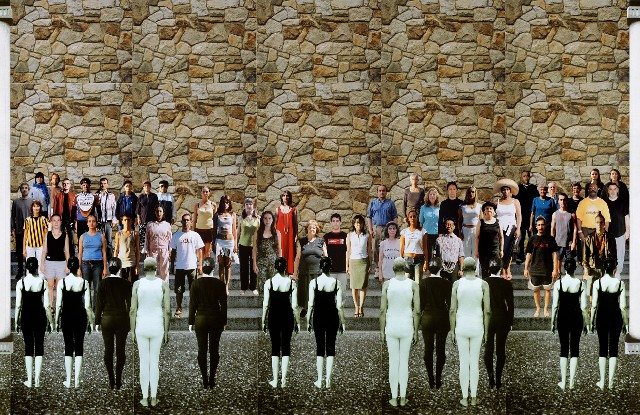

Walking into the spacious gateway room, Coleman and Blickley see a boxy robotlike construction arrayed with video screens and a clock, a much bigger simulated clock rimmed with photographs of Biro at different stages of her life, and three large photomontages baring the torments of our over-mechanized lives.

And so the tour begins.

In the course of it the two visitors will climb up and down three flights of stairs. They will view and hear works of art in every conceivable visual medium mostly by Biro herself, as well as creations among Biro’s family and friends. Under Biro’s conscientious guidance, they will regard pieces of “pure” and message-laden art, with a strong dose of surprise always present even among the more familiar. Both broad of brush and intimate as only a conception this personal can be, the House of Art will tell its guests something of Biro’s remarkable Old to New World story.

Born in Communist Rumania to a family of attorneys, high civil servants and creative doers, the teenage Biro followed her artist mother to Brooklyn’s Borough Park, ventured from her Orthodox Jewish upbringing to a degree in painting and sculpture from Pratt Institute and married twice while mothering three children. She won a Willis Award for her sculpture and showed work at the Hansen Gallery and the Organization of Independent Artists.

With help from teams of assistants and work crews. Biro inaugurated her House of Art, a “post-modern art attraction,” in 2009 in a corner of Sunset Park she calls “the land of no art,” all in her spare time from teaching in Brooklyn public high schools and her own continuing artistic work.

“There are three different ethnic groups in the neighborhood,” explains Biro. “Latin-American, Chasidic, Chinese. I’m right in the middle. Here they can all find hidden treasures. My whole life I planned a people’s museum, exactly like this.”

After a splashy opening with nearly two hundred guests, the House of Art received appointed visitors in earlier years while hosting well-attended musical and theater events. Activity has fallen off in recent years, although Biro has held well-attended art classes for local Chinese-American students, much of whose work adorns the walls of the first-floor kitchen.

In a testimonial letter to Biro, New York magazine art critic Mark Stevens wrote: “At once detached and passionate, given equally to cold-eyed analysis and hot-eyed rage, Biro creates images and tableau that portray, but do not yield to, the hellish side of the art world. Her despair, in short, is illuminating.”

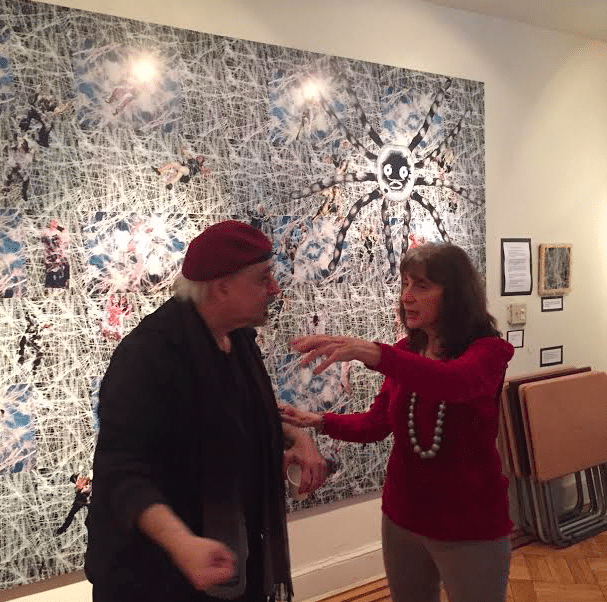

Sparks go off from the first minute in the big first-floor room.

Blickley bestows a gift on his host, a copy of Will Eisner’s graphic history of the Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Then, a hot-bubbling intuitive thinker, he swiftly plumbs meanings from Biro’s laboriously composed, dystopian wall allegories and illuminates archetypal links between the works no doubt cloaked to previous visitors. He sees the agony of electrocution in faces of cut-out photographed models trapped in a literal worldwide “web” composed of a rare industrial yarn. He notes the sculptural density in a photograph of a seated older woman, only to be told by Biro that the subject was, in fact, her sculptor mother. He comments on Biro’s choice of black-and-white figures, paradoxically standing for a life force against soul-robbing color, echoing the vibrant century-old black-and-white Biro family portraits from old Europe elsewhere in the House.

“I never thought of it like that,” replies Biro with a sage smile.

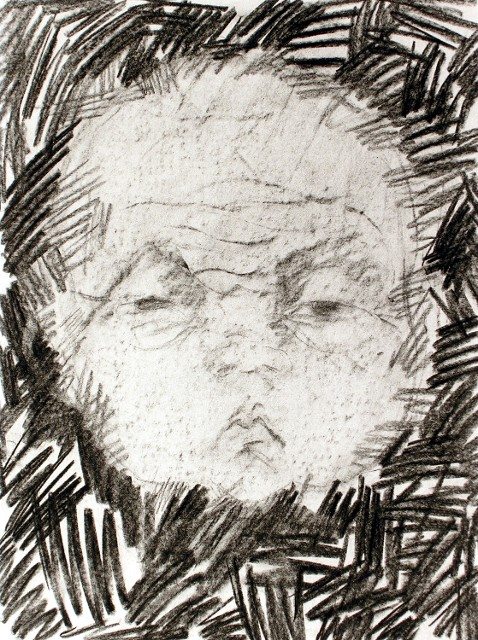

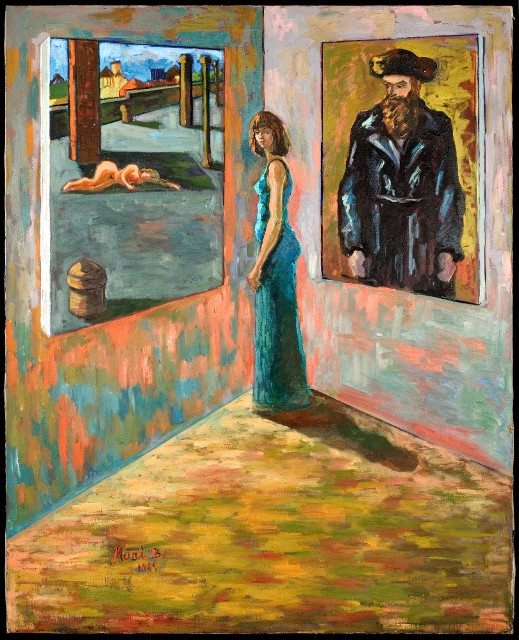

The tour continues through the various “wings.” Everything has a room, when artworks aren’t spilling out into hall space and stairways. Biro’s drawings offer the best testament to her Old World drilling in classic technique back in Romania, a feature lacking in contemporary American art schools, she insists, but for her a fundamental personal grounding that compulsively drives her, sketch pad at the ready, into the streets and subways of New York City. Her paintings and sculptures, based on her drawings and photographs, similarly hew to traditional representational models, touched with strategic departures like wavering gouges into the contours of her figures.

Personal Jewish touches are not in short supply: portraits in paint and clay of Biro’s late husband in a yarmulke and holding a kiddush cup, a carved child resting a weary head against his shtraimeled grandfather, Chasidim seated on the D train, a painting-within-a-painting of a rabbi bound inside a picture frame gazing at a young woman and a world of desire beyond his grasp.

Says Coleman: “I’m seeing walls. A lot of walls. I’m thinking of the Wailing Wall.”

There are also a lot of children’s book watercolors—which Biro unapologetically calls “kitsch”—and many versions, some borderline surreal, of Raggedy Ann and Andy, another admitted obsession of Biro’s. But the centerpiece of the House of Art is Biro’s robots, a prize fixation that yields an occasional “good” robot, like the first-floor anthropoid kiosk prototype for a compact multimedia people’s space that would be open to an endlessly rotating display of art from interested citizens. (“It’s a gift to artists everywhere,” remarks Coleman. “It’s a kind of promise.”)

But most of the robots stand firmly in the “bad” category, leading the charge to a soulless tomorrow or a spirit-crushing present where inquisitorial curators, which Biro called the “Cultural Elite Machinery,” strip artists of their last spark of originality.

Biro plants her cyborg tyrants on her epic wall montages, in elaborate stage tableaus evoking Torquemada and Fritz Lang, in a deep-focus diorama, adorned with gold-leaf paint, that lend a nightmare turn to an old European royal court, much of it with black mass-like audio effects.

“I love the big hands of the inquisitors,’” says Coleman. “It’s the part that makes them most alive.”

As Coleman and Blickley discover, their host, a demure wraith in more casual interaction, is also a woman of passionate beliefs, firing her eyes and setting her jaw when the right subject finds its nerve. In Biro’s account, it’s a belief system earned the hard way, between life in Nicolae Ceausescu’s dictatorial Romania and the stifling education and art bureaucracies of New York.

A weighty textual distillation of her philosophy, “One Artist’s War against the Invisible Enemy,” a championing of the creative imagination over the many contemporary forces arrayed against it, stands for sale in the House’s front room. (“Art is a poetic protest against evil,” reads the book’s epigraph.)

Last year Biro moderated a panel on the artist’s role in society at New York’s National Arts Club.

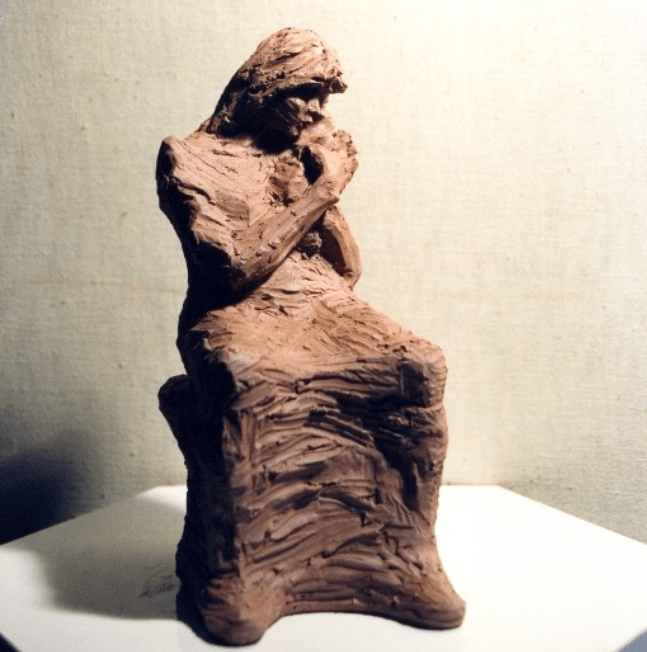

Throughout the house, in cabinets, in boxes, on near-random surfaces, are upward of a thousand clay sculptures by Biro’s late mother, Agnes Marmarosch. Moving to Arad, Israel late in life, Marmarosch developed a loyal following for her works, virtually all of them no larger than pieces of a chess set. Spindly yet gratifyingly substantial (“like Giacometti and Rodin,” observed Blickley), most of the pieces portray shtetl-like Jewish scholars, musicians, and street merchants. Others represent biblical figures as well as depictions from the contemporary worlds of fashion and pop music.

“She made people so happy with her sculptures,” says Biro. She hopes to introduce her mother’s work to a wider American public.

The last stops are the basement screening room where the guests viewed “making of” films on several of the exhibitions they had just seen, as well as the “adult room,” containing frank nude (but unpornographic) painted studies, plus a pointed but erotically antiseptic photographic print of an installation that meditated on museums’ shallow fix on sex and art.

Biro crowns the tour with a special serving of her own homemade “gulyas” (“goulash” in American). She speaks of hopes to restore the House to its popular glory days. One plan: open its space to exhibitions by Chinese-American artists.

Coleman and Blickley say goodbye to the House of Art.

“It’s not just a house, it’s a whole lot more than a museum,” says Blickley. “It’s a temple.”

“I love how art is built around a home,” Coleman adds. For her, it stands as a bright note in a season of an unpredictably changing climate and political volatility.

“It’s a festive moment in time,” she declares.

Visit the gallery at 834 44th Street between 8th and 9th Avenues. For information and to arrange a tour, visit the Art House website here.