Manhattan Beach Native Makes Historic Solar Eclipse-Chasing Flight For Rarest Of Photos

Space shuttle photographer and Manhattan Beach native Ben Cooper made history this weekend when he joined 11 other photographers aboard a privately chartered jet to get a rare glimpse of a “zero second” solar eclipse.

On Sunday, the moon passed between the Earth and the sun at a rare and perfect angle, to cause what’s known as a hybrid eclipse. During a hybrid eclipse, the moon is close enough that from certain points on the globe it appears to be a total eclipse, while from others the moon appears smaller, and leaves a bright ring around the disk of the moon.

While total solar eclipses occur every one- to-2.5 years somewhere along a thin path on the Earth, they only last a few minutes. Hybrid eclipses, on the other hand, are an even tougher find. They only occur once in a decade, and the total eclipse path is much more narrow, lasting less than 10 seconds in some areas.

Cooper, a former NASA photographer and professional spacecraft shooter, who we’ve featured previously for his photos of the Space Shuttle Enterprise passing by Southern Brooklyn by air and by sea, set out to capture the elusive moment of total solar eclipse. It would be the fourth total solar eclipse of his life.

It was most visible from parts of Africa, Europe and the eastern coastline of the Americas. But Cooper set his sights higher, much higher, and joined a group of international photographers on a historic flight to capture the total eclipse from above the cloud-line.

It’s not unheard of. During almost every eclipse, tourists and eclipse chasers will book flights, sometimes on jets as large as a 747, to catch a glimpse.

But the unique nature of this particular hybrid eclipse meant a very special flight path.

“Most of the time, what the plane does is go up and fly along the path of the eclipse and wait for the shadow to catch up from behind, making it fairly easy,” Cooper explained to Sheepshead Bites. “The geometry of this eclipse meant, that to see it out the windows, we had to intercept the eclipse at 90 degrees, like two cars meeting at an intersection. Except the cars are going 500-600 mph (plane) and in this case 8,000 mph (the eclipse where we were).”

Meeting the eclipse at that angle – perpendicular – was the first of its kind mission in human history.

It wasn’t a flawless trip. What they had hoped would be a seven-second eclipse got cut short due to minute variables in that mind-blowing geometry.

“To do this meant the plane had to get to one spot at one instant. We were, in fact, about one second off and so, instead of getting what we predicted to be seven seconds of eclipse, we got less than one. Maybe zero,” he said.

Still, at 42,000 feet over the Central Atlantic, the plane made a near-perfect intercept of the eclipse. Cooper said the sensation at that successful moment, even if it was for less than a second, was worth the effort of a last-minute shuttling to Bermuda, from where the chartered plane departed and landed.

“It was an amazing experience, not knowing whether we would get it right until it actually happened,” he said. :The navigator and pilots were amazing at getting us to the right spot at the right moment. I still can’t believe we did it successfully, even if a hair off!”

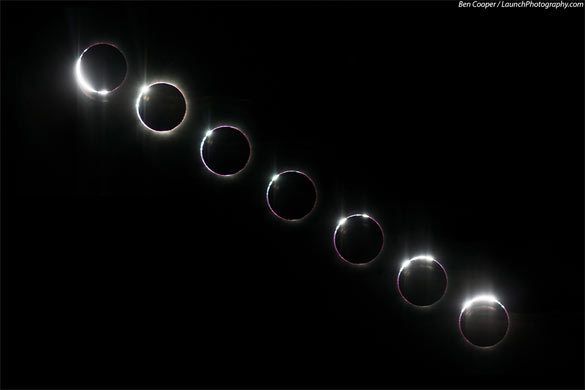

Below are the photos Cooper captured of the eclipse. Be sure to check out his website to see more photos from this and other shoots, and purchase your own prints.