The Irish Of Flatbush — The Early Years

The history of the Irish in Flatbush is a long and rich one.

In honor of St. Patrick’s Day, we are publishing a lengthy excerpt from the wonderful “Flatbush Neighborhood History Guide,” written by Adina Back and Francis Morrone, and published in 2008 by the Brooklyn Historical Society.

Back and Morrone start off by discussing 19th century Irish immigrants in Flatbush, many of whom were fleeing the Great Famine.

“By 1855, 35 percent of Flatbush’s population was Irish-born, which was comparable to the Irish-born population in the ‘eastern section of the city,’ i.e., Brooklyn Heights, Fulton Ferry and Cobble Hill.

Flatbush landowners depended on Irish immigrants to work on their farms since the area’s enslaved population was freed. By 1860, 59 percent of farm laborers in Flatbush were Irish…

Escaping the brutal mid-nineteenth century famine in Ireland, this first wave of Irish immigrants eagerly sought economic opportunities in America. While most worked in the expanding industrial sector, Flatbush’s Irish also found familiar work as farm laborers, or as trades people such as blacksmiths, carpenters, stonecutters, masons, painters and plasterers.

Irish women worked almost exclusively as servants and housekeepers for the town’s wealthy elite.

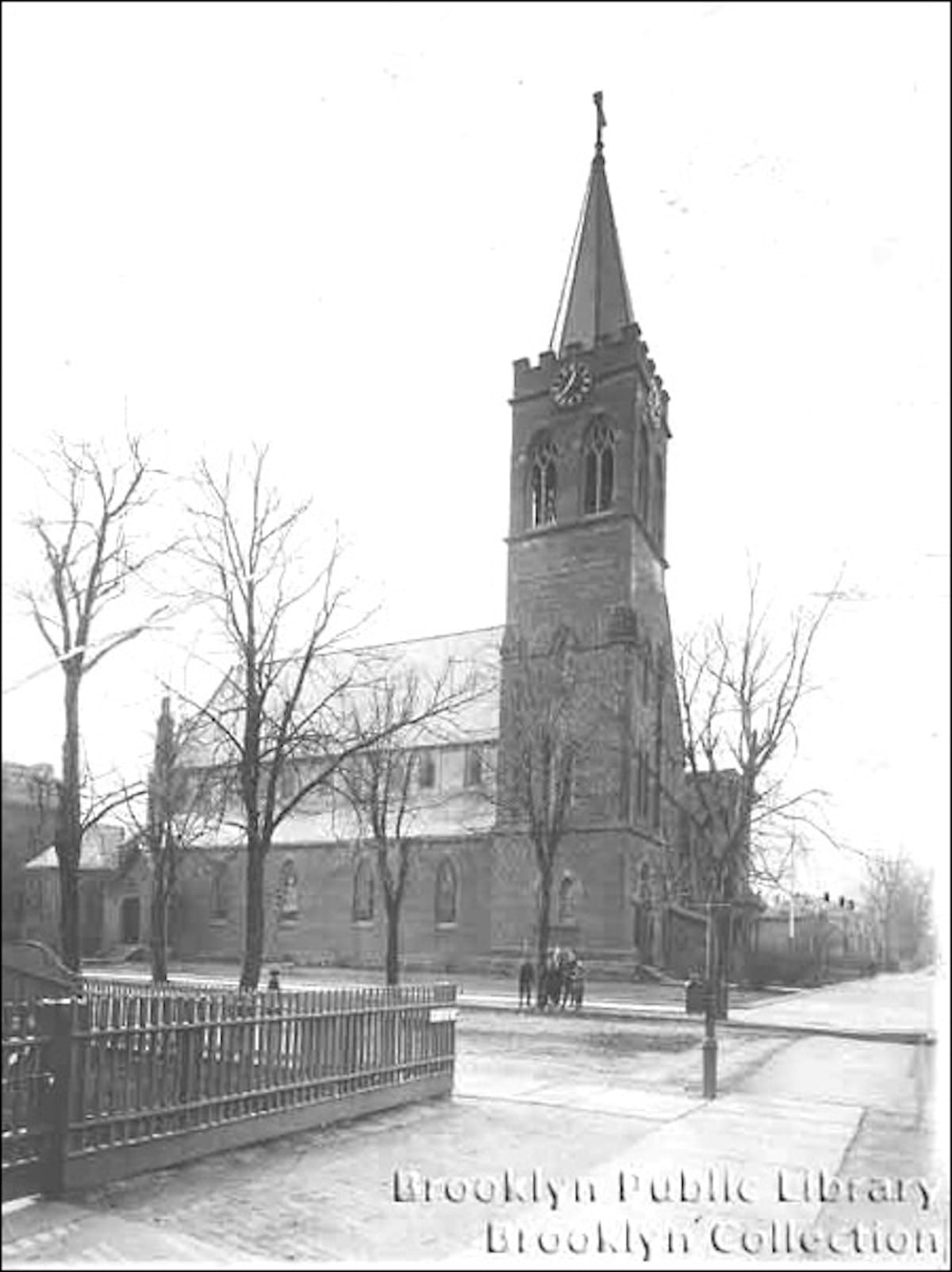

The new immigrants quickly built the institutions necessary to create community. In 1847, they erected Holy Cross Church, the first Catholic church in Flatbush. The cemetery followed soon thereafter and was a burial site for the town’s Irish residents, including Civil War soldiers and veterans.”

Another wave of Irish immigrants arrived in Flatbush in the early to mid-20th century, after the town had been absorbed into the city of Brooklyn (1894), and then into New York City (1898).

“First and second generation Irish Americans also emigrated from Manhattan and joined the Irish population in Flatbush that had existed since the middle of the 19th century. They settled close to St. Teresa’s and Holy Cross parishes.

The presence of a large number of Irish immigrants from County Donegal attracted others to come to Flatbush in the 1930s through the 1950s.

John Ridge, the Irish historian of Flatbush, described Irish families gathering on weekends in Prospect Park to picnic and play “Irish” football on a small hill in the northern section of the park that they coined “Donegal Hill.”

Like other immigrant groups at the time, the Irish had mainly blue-collar jobs, which often helped them to move into the middle class. They strove to maintain their cultural traditions, and remained connected to political struggles in their home country.

“The Irish in Flatbush worked as subway drivers and conductors, stone cutters and masons, clerks and milkmen, merchants and grocers. The Flatbush Water Works employed many Irish workers, and its Chief Engineer was an Irishman named John Geoghan, Sr.

Irish woman continued to work as domestics, some coming from other Brooklyn neighborhoods to work in the homes of local Jewish families.

They frequented the taverns of Nostrand Avenue where Irish music played, and the dance halls to the north of Prospect Park with names like ‘The Pride of Erin’ and ‘Erin’s Isle.’ These cultural gathering spots were designed to help Irish residents meet spouses and solidify social ties….

In the 1920’s, the local Irish community raised funds in support of the Irish war for independence from Great Britain. However, as the war for independence evolved into a civil war, the Irish in Flatbush became as divided as their compatriots overseas.”

Post World War II-era government policies helped to transform Flatbush’s ethnic identity, spurring an exodus of some — but not all — Irish-Americans.

“Like many white urban dwellers throughout the nation, Flatbush residents took advantage of the mortgages offered by the Federal government through the 1949 Federal Housing Administration Act (FHA), and bought homes in the booming suburban housing markets.

With the GI bill, World War II veterans gained access to a college education and an opportunity to move into more skilled and professional jobs. Flatbush’s predominantly Jewish and Irish-American populations began to leave for Westchester and the Long Island suburbs.

By contrast, FHA’s racially discriminatory lending practices effectively kept African Americans out of the suburbs.”

Do you have Irish roots in Flatbush? Is your family still here? We would love to hear your story.