Ignored By City, Gerritsen Beach Comes Together In Recovery Efforts

By Paul Moses

Owning little more than he wore, Paul Paradiso lumbered forward on crutches into the cool dark training hall of the Gerrittsen Beach Fire Department to see if he could find some clothes.

Doreen Garson, assistant chief of the Vollies, as the volunteer department is called, told him to look inside the big plastic bags heaped on a set of folding tables– there weren’t enough people available yet to sort clothes local residents had donated.

Like nearly everyone living in Gerritsen Beach’s old section, Paradiso, 42, was wiped out Monday night by the rising floodwaters from Hurricane Sandy. The couch floated in the living room of his Canton Court home and the refrigerator flipped over and drifted in the kitchen. His wife, Michele Thorne, 45, said she nearly drowned trying to move their Volvo to safety; she and her 17-year-old daughter got out when the window opened automatically. Then they linked arms and held onto a street pole to withstand the water gushing through their street.

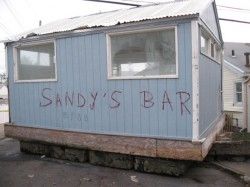

There are harrowing stories to be heard everywhere in Gerritsen Beach, as in Sheepshead Bay, Manhattan Beach, Brighton Beach, Coney Island, Sea Gate and Rockaway. But somehow, Gerritsen Beach has largely escaped attention, especially in the daily newspapers. The New York Post did, however, run a 150-word story in Thursday morning’s paper that called the Gerritsen Beach “the forgotten disaster zone.” A few broadcast news operations then reported from the neighborhood on Thursday.

“We sort of got lost in the mix over here,” Thorne said as she paused from looking through piles of clothes to find a coat for her 12-year-old son, Christopher Thorne. When she had the opportunity on Wednesday, she posted her own message-in-a-bottle on Facebook, saying that “We need help” and “nobody knows how bad it is out here.”

Still, with or without attention, Gerritsen Beach seemed quite capable of taking care of itself. The Vollies, working with the pastor of Resurrection Catholic Church, set up a shelter and all-round refuge with food, clothing and heat in the parish hall on Gerritsen Avenue.

Local residents didn’t want to travel the nearly five miles to the closest city shelter, located at Franklin Delano Roosevelt High School on 20th Avenue, said Michael Zuosta, an officer in the Vollies who assisted at the shelter. Besides, the saltwater surge had destroyed most of the cars in the neighborhood.

By 2 a.m. Thursday, the Mayor’s Office of Emergency Management provided some cots, Garson said, adding that State Senator Marty Golden had helped arrange assistance. “The city kept saying they were going to get back to us,” she added.

The biggest concern, Garson said Thursday, was that when power returned to the neighborhood, fires would follow as the electricity ran through flooded homes. Volunteers, city inspectors, and National Grid workers were going door to door, trying to make sure electricity and gas were shut off. In some cases, residents weren’t home.

“We don’t have enough manpower,” Garson said.

But Garson, who grew up in Gerritsen Beach, said she understood. “The city is so overstretched … We’re used to taking care of ourselves.”

Gerritsen Beach is in “Zone B” – a secondary flood plain where evacuation was not mandatory. It’s surrounded on three sides by water, but Plumb Beach and the Belt Parkway to the south serve as a protective barrier. As a result, the speed and severity of the flood surprised many residents.

Paradiso said he was trying to lighten the atmosphere by watching the movie comedy The Dictator when the flood struck. “You figure you laugh a little bit,” he said.

When the water suddenly surged, he tried to keep it out by putting towels under the front door. Then he improvised with wet towels to build a sort of channel that funneled the water into the basement. But the space below filled up, and the water kept rising on the first floor. His wife, having survived the flood that consumed their car, was in water up to her shoulders on the first floor.

The family took refuge upstairs; most of the couple’s belongings were destroyed on the first floor, where their bedroom is located. Paradiso, a mechanic who installs electronics on cars, said his car was destroyed – saltwater damage can’t be reversed, he said, adding as he pointed out at the street, “Every one of these cars here is just a pile of steel.”

In a neighborhood with little mass transit – one bus line on Gerritsen Avenue – not having a car seems to compare to the shock of losing a home. “A car is not like losing a couch or something,” Paradiso said. “You lose your car, you lose your outlet to the world.”

Rental cars, generators, gasoline: These are things Gerritsen Beach residents need right how.

Still, Paradiso said, he was thankful to live in Gerritsen Beach. In the midst of the flood, neighbors had burst through his door to see if he was safe; he had recently undergone surgery on his leg and was using crutches to walk.

“The people around here are top-notch,” he said. “That’s the most important thing.”

Pat Mooney, 45, who pointed out the mark showing that water rose to four-and-a-half feet on his home on Seba Avenue, said much the same. He and Eddie Brancale, 45, and other neighbors were out in front of his house, warming themselves before a blazing fire – they had put some logs on the gas grill.

“I’m grateful to God that I live in Gerritsen Beach because I have such good neighbors,” he said.