Golnar Adili Tells The Immigrant Story of Separation and Anxiety Through Art

CLINTON HILL – Just below her right shoulder, there is a quote inked on Golnar Adili’s skin. Unless one knows how to read the curves and dots of Persian, it is foreign—just like Adili herself.

“I can do without the world, but I can’t do without you,” is 41-year-old Adili’s own translation of Rumi, a 13th-century Persian poet still admired by millions today. The words were permanently etched on her body in memory of her father who passed away 15 years ago; her father, who was an activist fighting against the Shah in the Iranian Revolution.

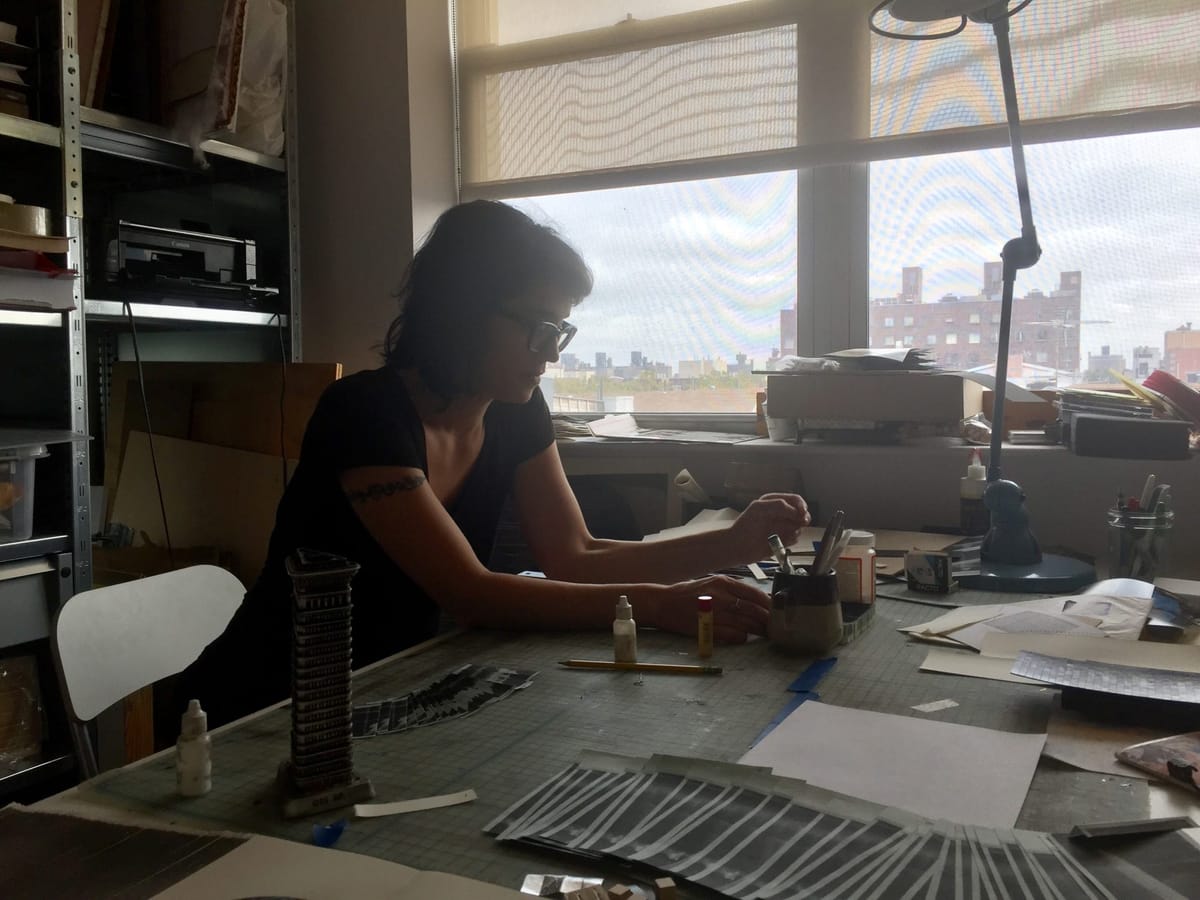

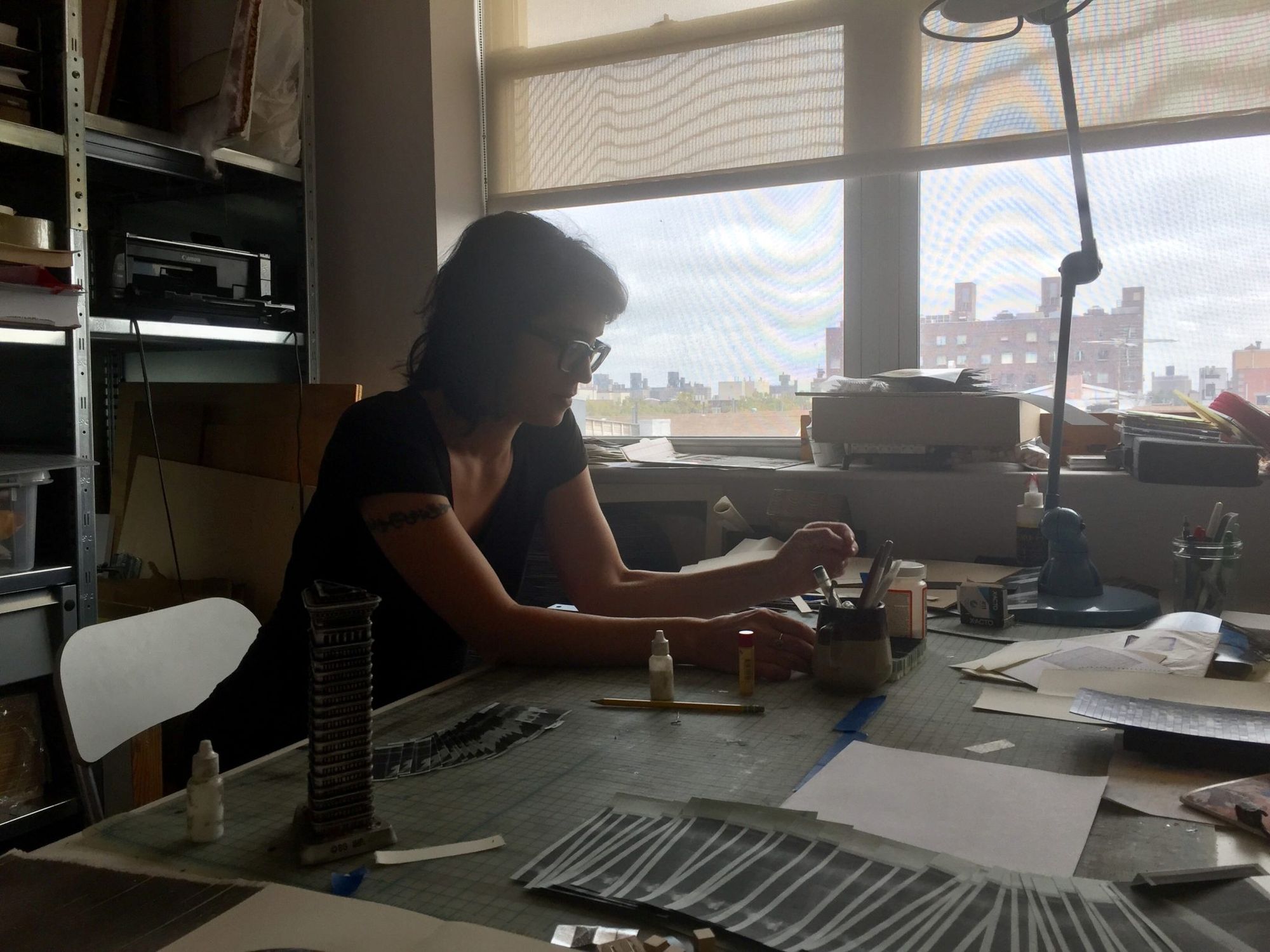

Adili, a tall, lean, woman with short brunette colored hair and big frames on her glasses, uses art to express herself. She tells stories of things that have inspired her, things she finds beautiful, and most importantly her father. Coming to the US, that is exactly what she brought along: her culture, her language, her experiences, her artistic talent, and the memories of her dad. All of which she would mesh in her art and her Clinton Hill home.

Adili was born in the suburbs of Washington D.C in Northern Virginia. Her parents had come to the US to study in college and she is their only child. Her father went back to Iran to fight against the Shah and her mother decided to take young Adili, then four, to go to be with him in Tehran. Later on, her father had to escape, but it was her mother who could no longer leave. Adili became stuck in between two parents, in between two different worlds. When she was 18, she left Tehran to attend college and be with her father in America.

She calls herself an immigrant.

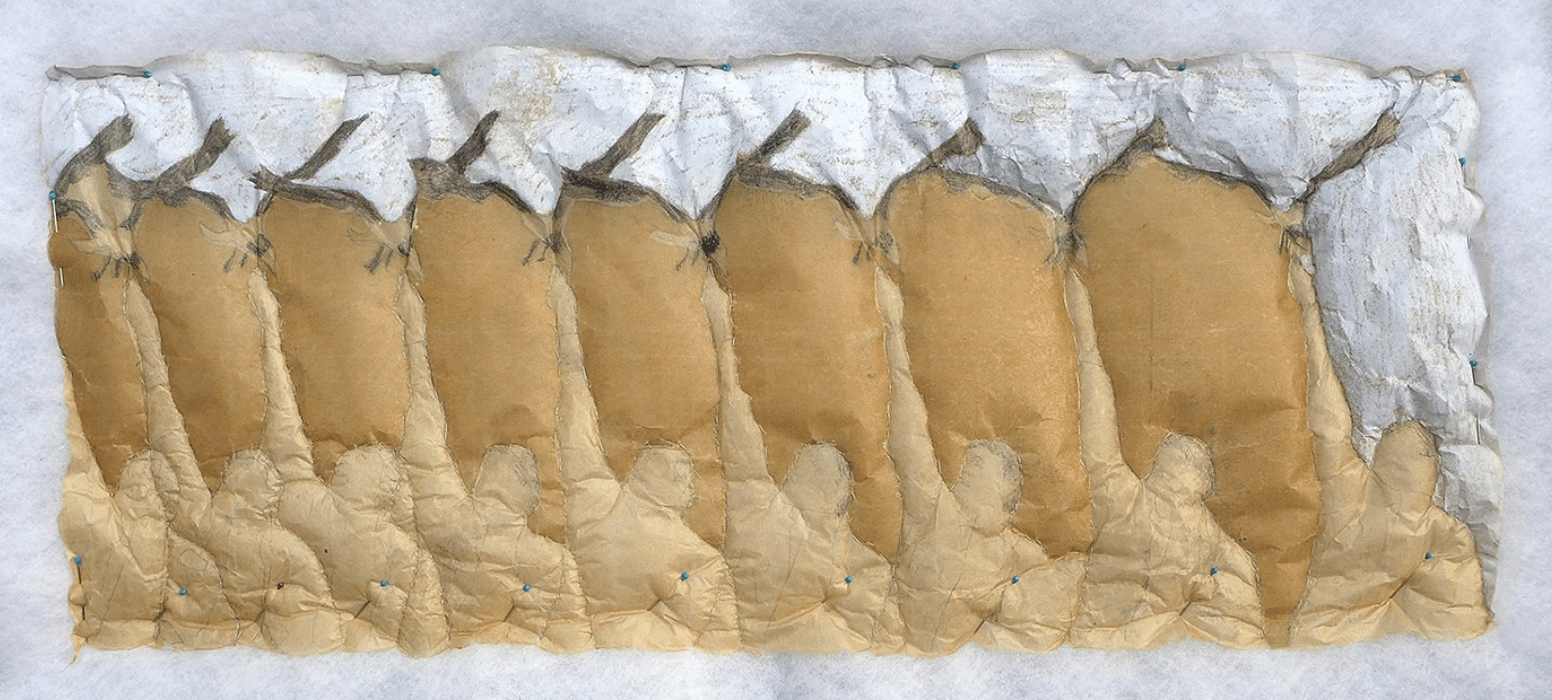

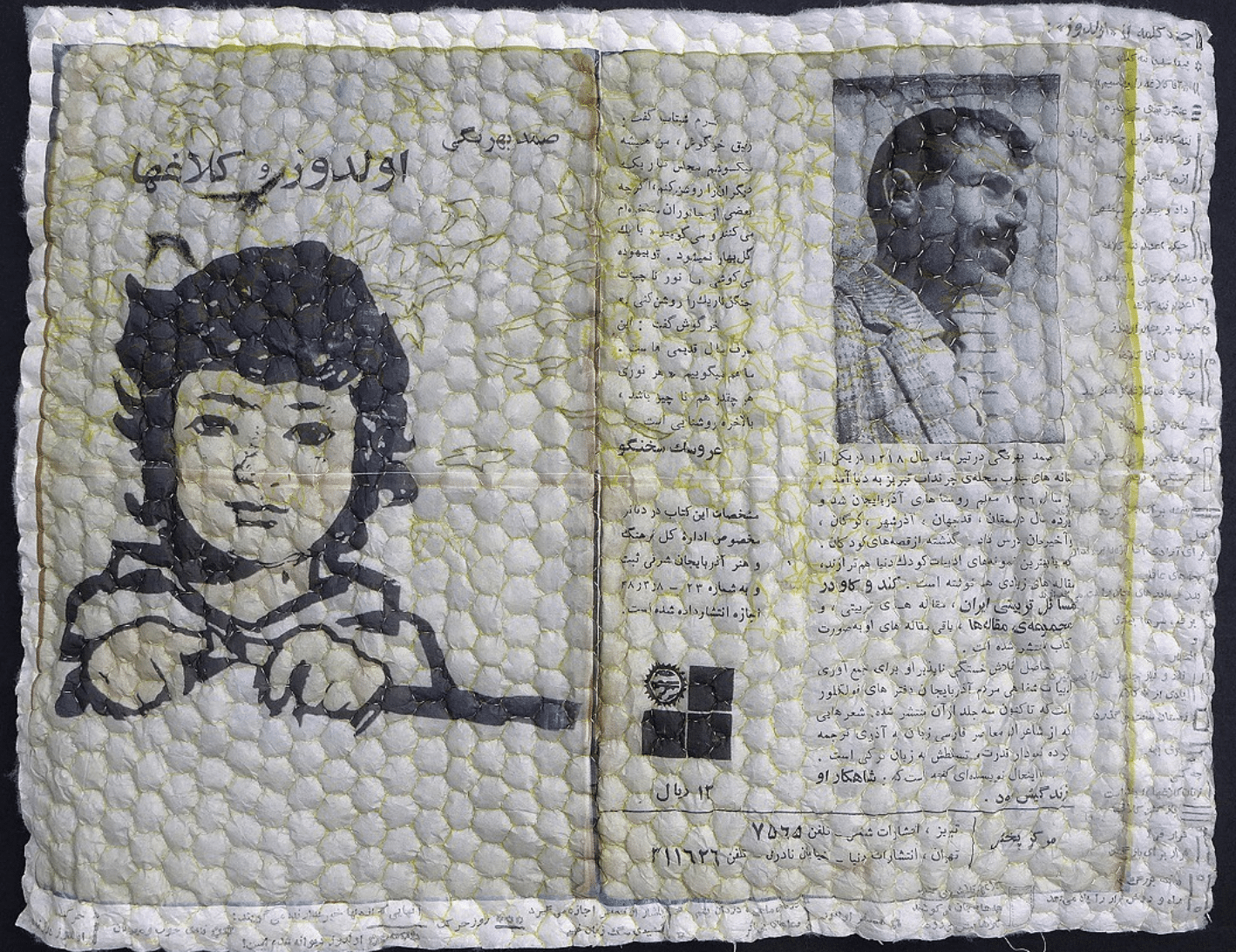

A mixed media artist who works a mostly with paper, her artwork revisits the themes of longing and separation – a common immigrant story, filling the walls of her apartment.

Displacement is one such collection of her work, “inspired by my father’s archive of photos, letters and travel documents meditating on diasporic longing.”

Some of her artwork is colorful, some dark. There are edges and lines, small collages of photographs, that draw you in. Her art is so eloquently simple, yet as your mind wonders, you won’t notice how the time goes by.

“I can’t really say my art is about one thing, it’s about what intrigues me. It could be from now or the past,” Adili said. “As an artist, I feel like you don’t choose to do art. It’s something inside you that really tortures you or propels you to do art, especially since it’s something you don’t get material gain from. It’s really a work of passion. I am a very visual person, and maybe because I have experiences that in no other way I can express, and get out of myself, I use art for it. It’s a very strong feeling. “

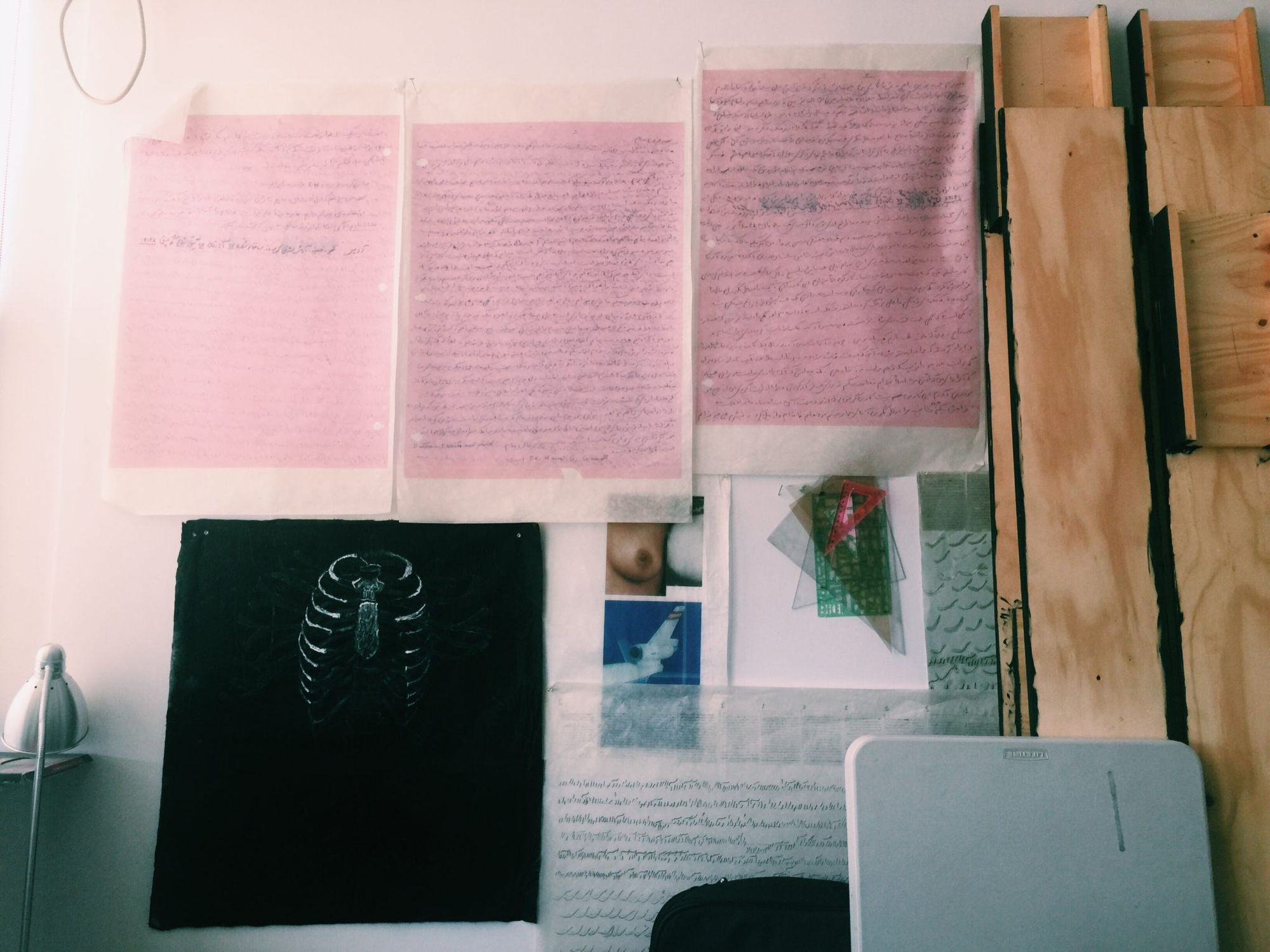

Her small studio is in the nook of her apartment. There’s a big brown cardboard box sitting on the floor of the entrance, so her eight-month-old daughter Assia Anaar doesn’t crawl in. The room is filled with photographs, a big table, pieces she’s working on, quotes that inspire her, and a big window letting in the sun. There is no door.

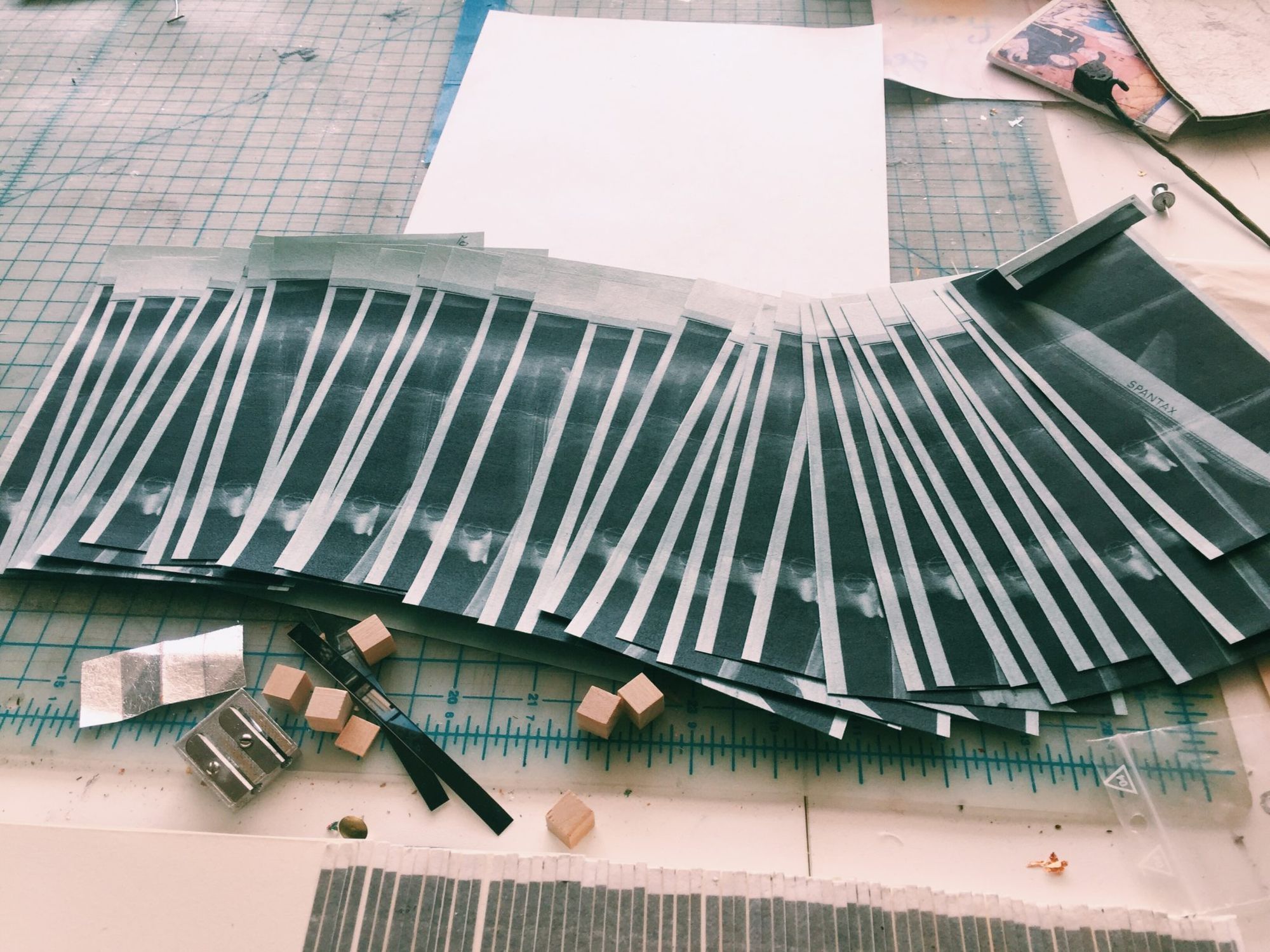

“I work a lot with paper-based materials, because I have a love for it, but also because it’s readily available,” Adili said. “It doesn’t make a huge mess in tight spaces, and I can’t afford to have a separate studio, so I can just work here in my house and it’s cleaner.”

One of the artworks she is currently working on includes multiples copies of an airplane flying in the sky among the clouds. It is the airplane her father escaped out of Iran on.

The Iranian Revolution, also known as the Islamic Revolution, began in 1979 and led to the overthrow of Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the Iranian king. Though the revolution itself lasted about a year, Iran wasn’t entirely at peace. On September 22, 1980, when Adili was four, Iraq invaded Iran, starting eight years of war.

“There were missile attacks, bomb attacks, on and off. It would get intense sometimes,” Adili said. “When it was really intense, we would go out of the city into the countryside where we had family, where we were less of a target.” Adili spent her days in school, hanging out with her friends, and sketching portraits on the streets of Tehran for pocket money. She wanted to be an architect.

“Architecture was a nice combination of art and science. It’s a mixture of a lot of technical skills but also conceptual thinking and reasoning,” Adili said. “And it also seemed like a practical discipline coming from Iran. Everyone wants their kids to be engineers—not that my family was very much like that—but still, there were those expectations. Even unspoken expectations. So, it took me a while to figure out my own path.”

In 2004, she received a Masters of Architecture from the University of Michigan. But two years after graduation, she realized art was more important to her.

“I always loved artist biographies and was always artistic myself, but came to a final realization after trying so many different things – which I was not bad at, it just didn’t click,” Adili said. “I say I got to art by a process of elimination. Once I started to pursue it I knew even more that it was for me.”

She also works very intimately with the human body—specifically the chest. “You store your emotions in your chest,” Adili said. “I find the body beautiful and use my own body as a self-portrait.”

Her depictions of human breasts are one of the many things her friend and fellow Iranian artist Nooshin Rostami likes about her art. “The way that she deconstructs and recreates these beautiful artworks is so stunning you want to stare at it for so long,” Rostami said. “But you can also feel the pain and vulnerability.”

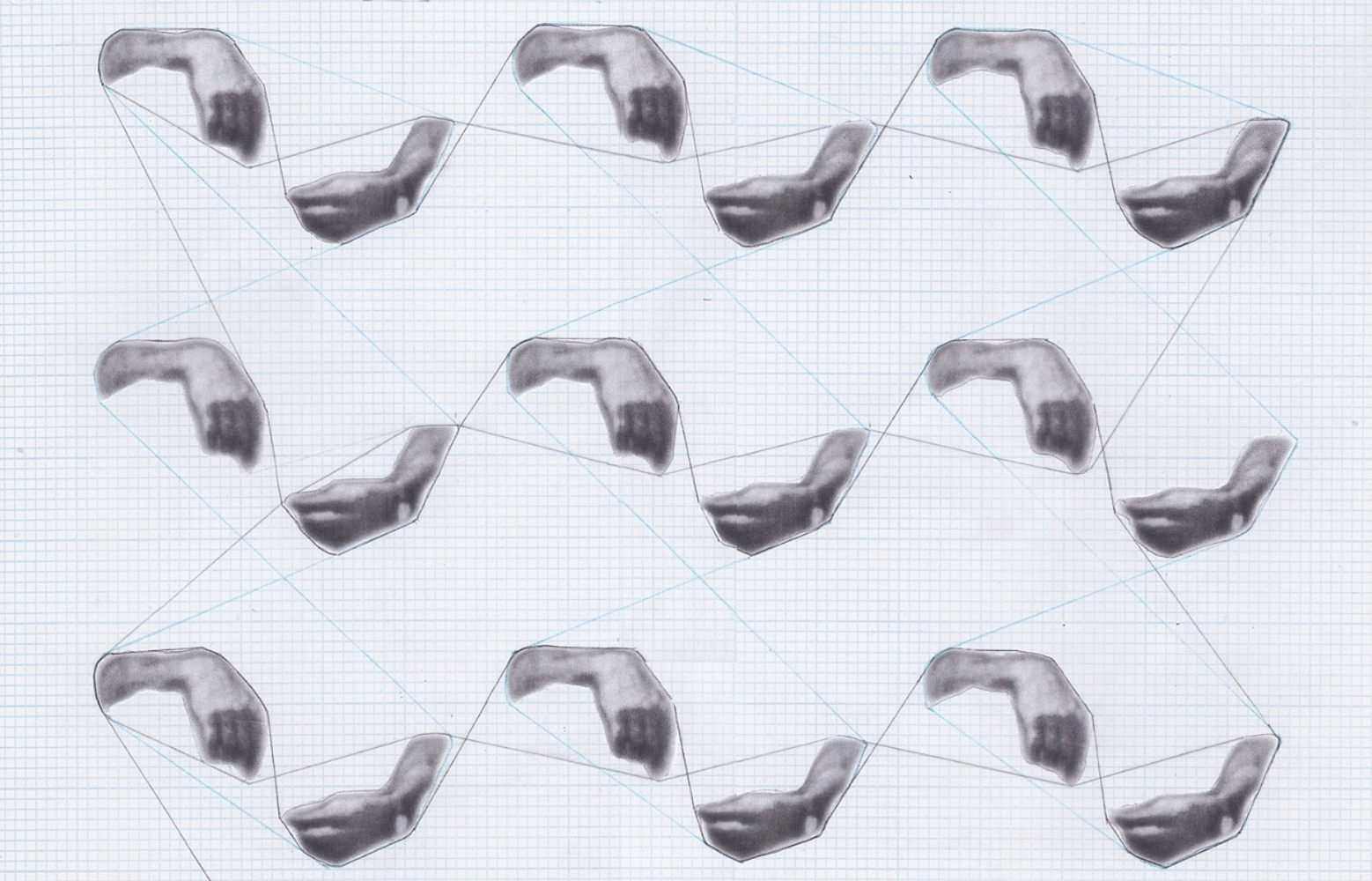

On the wall of Adili’s studio, are small sketches of wrists and hands suspended in a web of lines, at once relaxed and tense, disconnected and connected, a partial story. They were her father’s, Adili explained. She uses memories of him, and any archives he left behind, in her artwork. It is how she remembers him.

“Being away from my dad was the most difficult thing,” she said. “After a while, you get used to those things as a child, but inside you really don’t. That separation and anxiety kind of built its way in my making, which is actually one of the themes that I work with in my work.”

While in New York, Adili found love. “I wish it could be a more romantic story,” she laughed. “I met him through a friend. He was visiting someone in NY and she brought him along, and we met and kept in touch.”

Her partner of five years Louis Wenger is from the French-speaking part of Switzerland, and he very much adores Adili. “She has a very big heart,” he said looking at her. “She’s a very good human being and I love her artwork.”

Adili has presented her artwork in various settings, such as in Munich, Germany, the Shirin Gallery in NY, and the Craft and Folk Art Museum in Los Angeles.

Though their daughter Assia has yet to visit Tehran, Adili herself goes back constantly. “Tehran used to be, right after the revolution, a lot of raw emotions. But now it’s become a kind of capitalist society,” Adili said. “It used to be a very beautiful, modernist city, but now it has become very chaotic and all over the place.”

But the city she now loves so dearly, was once a stranger to her.

“I remember I saw a clergyman with a white turban for the first time on the bus, and I said to my mom, ‘mom, why is he wearing whipped cream on his head?’ Adili said. She grew up Muslim, but was never religious “Or when there was Adhan (call for prayer) from the mosque, I was like ‘what is this music?’ I was in awe.”

To Adili Tehran is a bit like New York: “People are in a hurry, they’re not fake nice, they just want to get to their own business. And so there’s a strange sincerity in that that I like,” she said.

Through war, love, and family, art is what keeps her grounded. “Art is something I do. I definitely define myself as an artist,” Adili said. “But it is a lot about processing and healing the past, and making sense of the present.”

To view more of Adili’s artwork, check out her website.