Despite Historically Low Crime Across New York, East Flatbush Still Plagued By Violence

EAST FLATBUSH – “Safest Big City in America,” read the sign in front of Mayor Bill de Blasio and Police Commissioner James O’Neill as they announced the city’s per capita murder rate is the lowest in nearly 70 years and violent crimes are declining. “The New York miracle” is what O’Neill called it. But the miracle hasn’t cured some areas of the city.

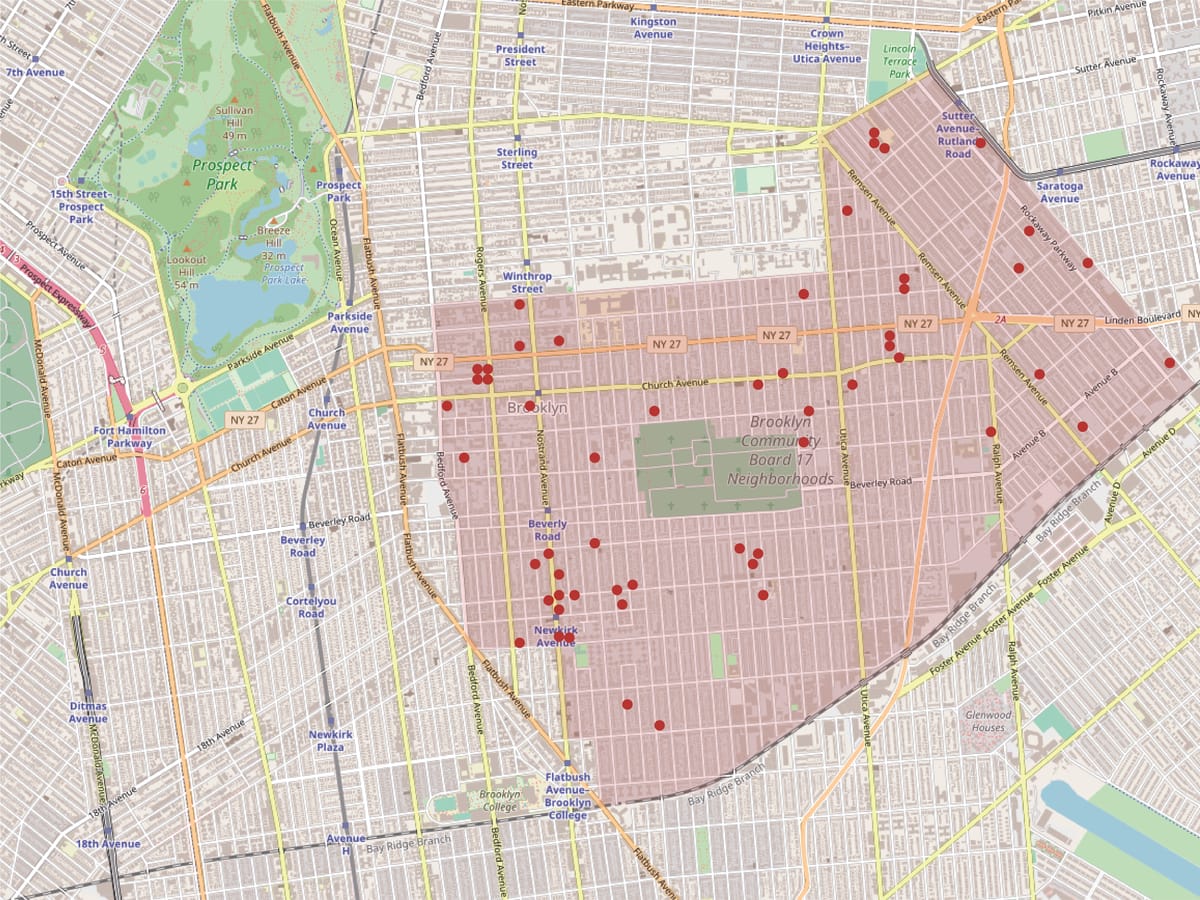

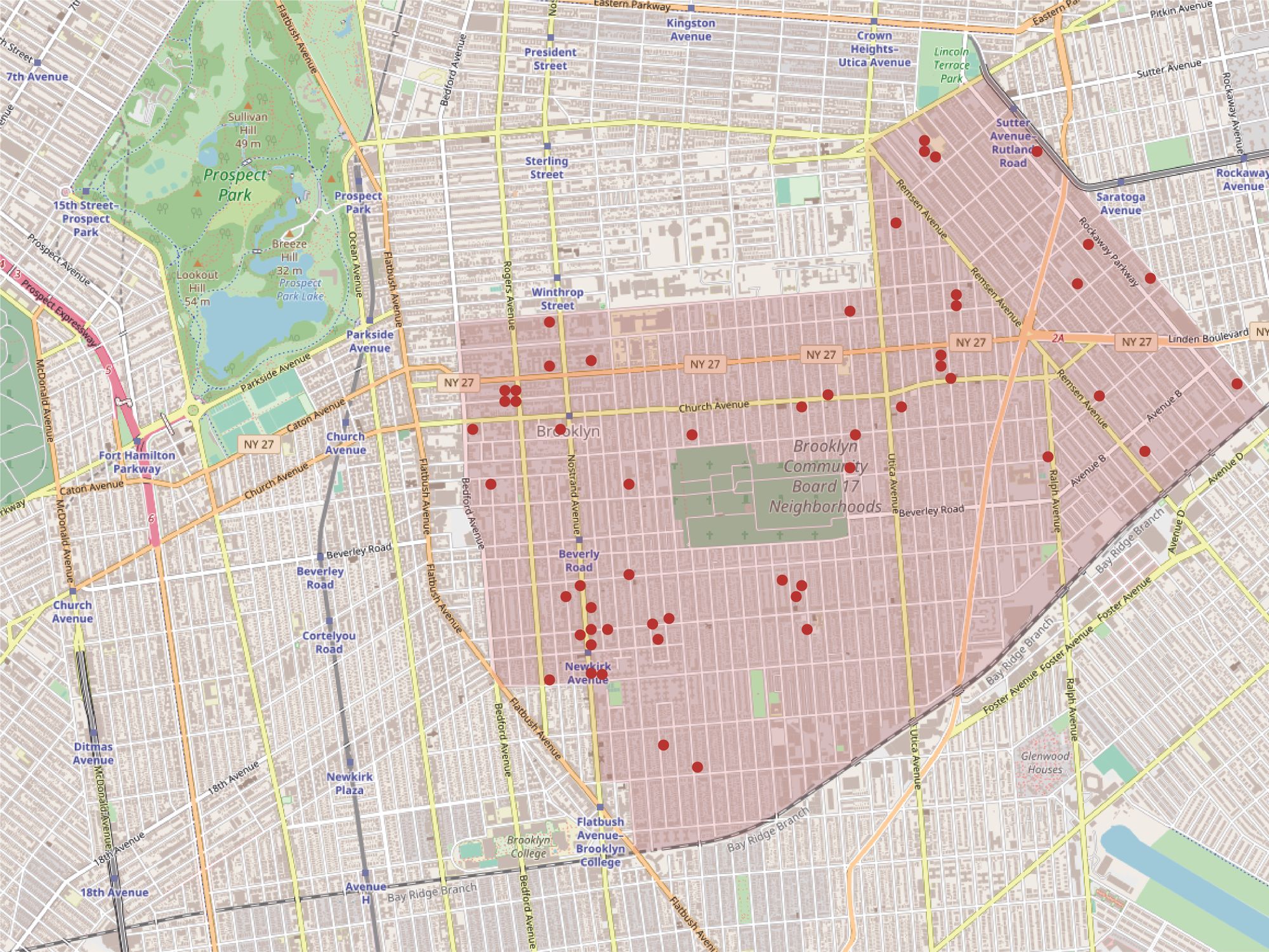

Residents of East Flatbush’s Precinct 67 still face daily violent crime. The precinct led the city both in shooting incidents and murders in 2017. The number of murders rose from 14 in 2016 to 17 last year, and the murder rate per capita is one of the highest in the city, more than three times the city-average.

The violence seems to stem from gang-related feuds or alcohol and drug-fueled disputes, according to the NYPD, who are cracking down on gangs, and conducting operations to arrest gang-members en mass in joint operations with other law enforcement agencies. The police have taken a two-prong strategy to crime reduction: targeting gang-members through a controversial gang-member database and building trust with residents through community policing.

At the scene of today’s shooting @NYPD67Pct #Anti_Crime_Team arrest three gang members & seize this illegal firearm #Great_Job #1LessGun pic.twitter.com/NNBcdtUsrV

— NYPD 67th Precinct (@NYPD67Pct) February 18, 2018

In the 67th precinct, officers regularly confiscate illegal firearms as well as reach out to the community, especially the youth through school programs and even a track team. Local anti-violence organizations are reaching out to youth and mentoring them to avoid violence as well. In regards to gangs, the organizations take a different approach, mediating gang-related disputes and providing a neutral meetings place.

In monthly community meetings, area residents pack out the 67th precinct to hear what the police are doing in the city’s most violent region. In one recent meeting, the commanding officer of the precinct, Deputy Inspector Elliot Colon, tried to reassure the crowd that flowed out the doorway of the police station’s meeting room. He and other officers from the precinct listened as residents voiced their concerns and ideas of how to prevent crime. But then one of the officers got a call on his radio and quickly exited the room. As he left the building, he was overheard saying, “One got shot,” to his partner.

Whispers quickly circulated around the room.

“Oh, God,” one woman at the meeting responded aloud.

A few minutes later, two detectives rushed out their office door, looking agitated.

About 15 minutes after that, two more officers walked out wearing jackets with “NYPD Evidence Collection Team” stitched on their backs.

In this incident, no one died, but the next day a dispute escalated into a shooting, leaving 44-year-old Mora Lyons dead. That capped off one of the area’s worst weeks this year for gun violence. By Saturday night, six people had been wounded in shootings. And by the end of the year, a local man who was part of the dance troupe that created “the Harlem Shake” would be murdered in his home.

In the NYPD’s tally of shooting victims, the number in precinct 67 dropped by over a quarter this year, from 76 in 2016 to 55 last year. But the precinct still outpaced any other by over 10 victims. In one span of blocks centered around the Avenue D and Nostrand Ave., seven shootings occurred last year, making it one of the most dangerous sections of the city.

Joon Kim, acting U.S. Attorney for the Southern District of New York, said in a statement, “There are rival gangs that are doing [sic], that are shooting at each other and maiming and killing each other, and there are innocent bystanders who are also [sic] who are being killed and being forced to live in areas where gun violence is a routine thing or where drugs are sold in the playgrounds.”

Some sections of the neighborhood have an entrenched history with crime dating back to the 1980’s. The area around the Foster Ave. and Nostrand Ave. intersections gained the moniker “The Front Page” in the 1990’s because the drug-related murders there were so brutal. To curb violence in areas like East Flatbush that have a long history of gang and drug-related crime, the NYPD conducts large, sweeping operations that target gang members. In the past year and half, police arrested more than 2,000 alleged members of gangs across the city, according to a NYPD news release.

But Godfrey Sandford, a long-time resident who regularly attends the precinct’s monthly meetings with the community, said gangs are a part of life in East Flatbush.

“We have a major gang problem in this community, in the six-seven,” he said.

An analysis of this year’s murders in the precinct reveals that about half were drug or gang related and about two-thirds of the victims were men between the ages of 18 and 35.

Jeffery Butts, director of the Research and Evaluation Center at John Jay College of Criminal Justice, said this is not a surprise. Men of this age are overwhelmingly the ones who commit and fall victim to violence across every type of community.

But he said that stricter law enforcement may not be the solution. Most often, it is personal relationships in the community that keep young people away from violence.

“When you have people you care about, and they care about you,” he said, “that’s what reduces violence.”

In East Flatbush, at least one organization is trying to create this community for young people. Gangstas Making Astronomical Community Changes Inc. (GMACC) reaches out to the most vulnerable young men to offer relationships that may steer them away from violence. They also mediate disputes between rival gang members in order to prevent violence.

Daron Goodman, the program manager for GMACC, said, “Our main focus with the youth is to change their mindset, then you can change their behavior, then you change the norm of the community.”

Often, the youth of the community see drug-dealing or violence as glamorous or a way to get rich, but that’s a false hope that leads to prison or worse, Goodman says. GMACC’s members know this first-hand – many of them used to be gangsters.

The founder of GMACC, Shanduke McPhatter, grew up in Brooklyn and joined a Bloods gang before being arrested for weapons and robbery charges. After serving 13 years in prison, he started the organization in 2008 to keep youth from traveling the same path he did. Today, the group runs mentorship programs, canvases the community for young people in trouble, and provides a safe space for young people to discuss their problems or resolve disputes.

“A lot of us are able to say, I’ve walked in your shoes, but you’ve never walked in my shoes,’” Goodman said. “’I’m going to tell you about my bad decisions, so you don’t have to make those bad decisions.’”

According to Butts, this is exactly the kind of relationship that can prevent young men from going down a violent path. It might be working. GMACC focusing on disrupting violence in the corner of the 67th precinct boxed by East 46th street, Linden Blvd., King’s Highway, and Snyder Ave. There was only one murder there last year.