Shahana Hanif Is The New Face Of Kensington

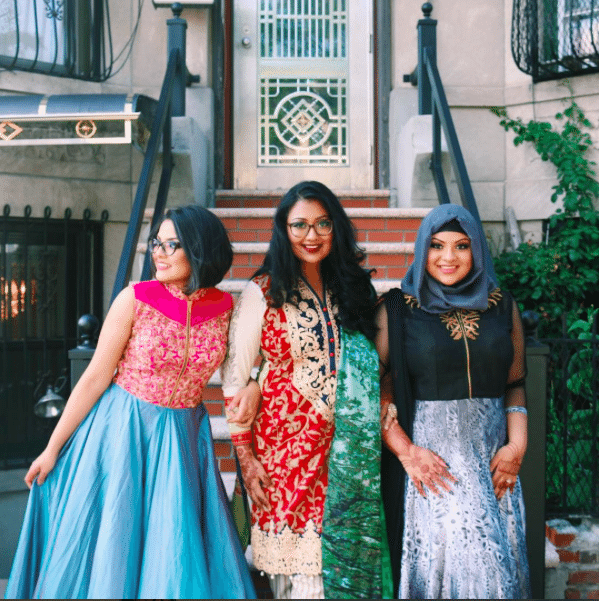

Kensington-based activist Shahana Hanif is a woman that embraces her many intersectional identities. She is a Bangladeshi, a Muslim, an activist, a writer, a performance artist and a 25-year-old woman living with a chronic illness.

“If people have complaints they should say it to me, I’m not scared of what anyone thinks,” she said, through confident laughter and dark, shining eyes.

We spent a rainy afternoon with Hanif, sitting outside at the Avenue C Plaza, relishing the cool drops slicing through a muggy September day. She has a deep, bellowing laugh she unleashes at the end of many stories, even ones that could otherwise be tinged with bitterness.

Hanif tells BKLYNER that both her writing and activism are shaped by her chronic illness, radiating from a platform of disability justice.

Hanif organized rallies protesting violence toward women and children; worked as a tenant organizer at Queensbridge Houses; and led the Muslim Writers Collective, among many other roles. She is a woman who isn’t afraid to challenge the traditions she was raised with, but also understands the deeply complex issues that bind a community together.

She grew up in the heart of Kensington’s ‘Little Bangladesh’, and was drawn to activism after being diagnosed with Lupus at age 17, while attending Bishop Kearney High School in Bensonhurst.

“I was going into my senior year, that summer I started experiencing migraines where I couldn’t lift my body off the bed,” said Hanif.

She was hospitalized for months, where “being in an ICU felt like solitary confinement,” she said. “While in the hospital, all my curiosities around being a brown, Bangladeshi, Muslim woman growing up in New York, in Brooklyn, were something that I was now questioning.”

As a teenager, Hanif went through chemotherapy, which caused dramatic hair loss and weight gain that altered her physical appearance.

“I didn’t have access to a mirror at the ICU, it wasn’t until I came home that I saw the changes and asked, what is it to be a woman with a chronic illness that changes the way she is desired. Am I desirable and do I have access to desire someone else?” she said.

Hanif transformed personal trauma into a local and global mission. “How do we cultivate societies that are more caring and deeply empathizing, rather than just leaving after the ‘How are you? Good?’”

And despite — or perhaps because of — her daily challenges, Hanif began writing about her experiences.

Her blog, Shahana with Lupus archives the honest voice of a woman etching out a physical, emotional and cultural identity. “It was important for me to shift the way that we think about bodies and differently-abled bodies,” she said.

Hanif talks about the role of her community during the first years of her illness with both gratitude and critical questioning. “I’m thankful that I was born and raised in a Bangladeshi enclave in Kensington; when I got sick everyone showed up. But at the same time, because of how I looked, people were addressing me differently. I heard taunts and suspicions around what’s happening to my body and why,” she said.

Hanif is deeply tied to Kensington. “The block over here was our safe place, where we played on our stairs. We claimed the entire road. I have tons of childhood friends who still live here, we’re adults now but those days are something that we hold onto because it shaped us,” she said, as the rain picked up around us. “I owe my community. I will fight ’till the end, through gentrification, or if something is lurking up on us.”

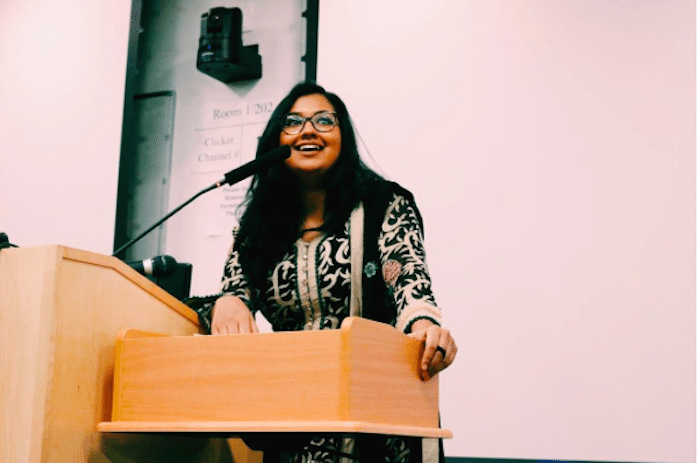

Hanif was the MC during the Kensington rally this summer, protesting the murder of Alauddin Akonjee and Thara Uddin, brazenly challenging the traditions of a patriarchal culture. “When I was up on stage that day, it was daunting. Some of these men are probably some of the same men staring at me when I’m coming home at midnight. There’s a fear about being a woman standing up there, and for me to have to prove myself,” she said.

The turnout and results of that rally were mixed, according to Hanif, who invited another local activist Hasiba Haq. Women came, but not as many from Kensington as Hanif had hoped, and there were more voices of elected officials than community members. “Everyone in the community is your uncle. I know they love me and respect me, but in terms of putting me up on a pedestal, it’ll happen once it happens,” she said patiently.

Hanif was the only speaker who addressed the complexities of the police involvement with the Muslim community, namely surveillance and informants. “The quick solution [for hate crimes and violence] is for immigrants to call on more police as protection, but when more police come in, that often is hand in hand with surveillance,” she told DPC.

At Brooklyn College, Hanif’s alma mater, informants caused an arrest that rattled the Muslim student community. “It’s hard for us to grow as a community when it’s being infiltrated by informants. They look like us, and talk like us, and go through training to behave like one of us and pinpoint those vulnerabilities, and especially target those in the community who are mentally unwell and vulnerable,” she said.

“They came to our friends’ wedding, but they’re acting,” she added.

From the rally podium this summer, Hanif also recognized some of the men who taught her Arabic as a child. “My early years were spent in the Masjid — everything from my first crush to learning to read the Quran,” she said.

“To me, separating women isn’t an Islamic practice but it’s a patriarchal aspect,” said Hanif. “My sisters and I learned the Arabic language and finished reading the Quran twice, then after that it was ‘you’re free to go now.'”

But that wasn’t the end of negotiating gender boundaries and power dynamics. “After each prayer of the day, there are men on the street. My sisters and I were taught how we are supposed to behave on the streets — to look down, make sure my chest is covered and I’m wearing something modest to not project the eyes onto me,” she said. “But we knew they were looking anyways.”

Hanif walks a delicate tightrope of uplifting and being critical of her community, which seem like two sides of the same coin.

“A lot of my good memories as a young girl are in the Masjid. But it was also the site where I learned that women get abused, either through being stalked or molested,” she said.

“I need the community on my side. It’s tough to reconcile. On one hand you’re abused, but you have to talk to your abuser to get them on the right side. I do talk about our mosques being spaces of abuse,” she said. For example, she performed a monologue during a South Asian adaptation of The Vagina Monologues, that told the story of a childhood molestation by two uncles in her house.

“Abuse is happening. But in my three- and four-year-old body, I already know that this happens to me and I have to keep it to myself. The cultural phenomenon around abuse is that you don’t talk about it. I’ve written and performed around that,” she said.

The main issues plaguing Kensington’s Little Bangladesh, said Hanif, are poverty, wage theft, domestic violence, and lack of healthcare, mental health services, affordable housing and job opportunities.

“I’ve seen the growth of Mosques — there are four — and the growth of population and small businesses on the block, but clearly what’s missing is more nonprofit organizations for young people, seniors and women,” Hanif said. “We’re still lacking a community center that can support people who need access to HRA benefits, social security, and healthcare. Young women need access to sex education. In a one-bedroom apartment housing five or six people in it, mental health issues build up.”

And not just any health care provider will be able to break the boundary — but doctors, lawyers and social workers who speak South Asian languages and understand the struggles of living in New York as a Muslim post 9-11, Hanif said.

“What I fear is that a lot of issues that exist are escalated because people don’t know how to speak English. A lot of women come here with a lot of skills, whether it’s cooking or sewing or craft work. How do we foster those jobs in our own community? People come here with the dream of opportunity, they’re not going to return home because they left for something better,” she said.

In her work, Hanif has helped many families overcome language barriers to secure better housing rights and healthcare; and resources that she shares in four guidebooks for Bangla speakers and organizers: Mental Health Resource List Muslim/South Asian 2016; Learn Bangla: NYC Resource Guide; language bank of organizing/social justice/feminist words in bangla; and how to be an ally for differently abled friends.

Hanif believes deeply in local, political engagement, but questions whether a political career is her path to engendering social change. She notes that many people hold tightly to their associations and political parties from Bangladesh. “These parties have shaped the way people live and interact with one another. That is a huge blunder to the community, because we live in New York, and participating here would make a difference.”

Hanif’s next step is a 6-month language immersion program in Bangladesh, where she is currently studying the language as a portal to social justice organizing. “I grew up speaking Bangla, and talking with shop owners here helped me strengthen my spoken Bangla,” she said. But without reading and writing skills, she felt like she could only go so far in her work.

“I need the language to talk about power in the community, and the intersections of being an immigrant, low income and Muslim. I need to know what power is in Bangla, hear how power manifests in New York in comparison to Bangladesh, and highlight the myth of the American dream, where so many immigrants have come and are living in poverty. I want to capture what the community is going through without having to rely on translation services. I want to be on the ground, and know every small business owner and have strategies on how to transform our community,” she said.

Follow Hanif’s work on her blog, twitter, and instagram. Read more about her continuing struggles with online harassment via Facebook here.